Installation view at the Sharjah Biennial, 2019.

All images courtesy of the artist

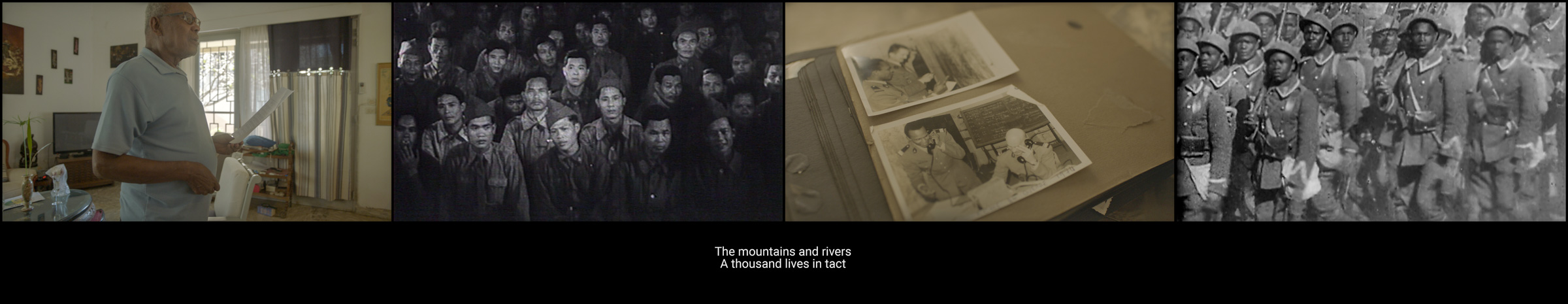

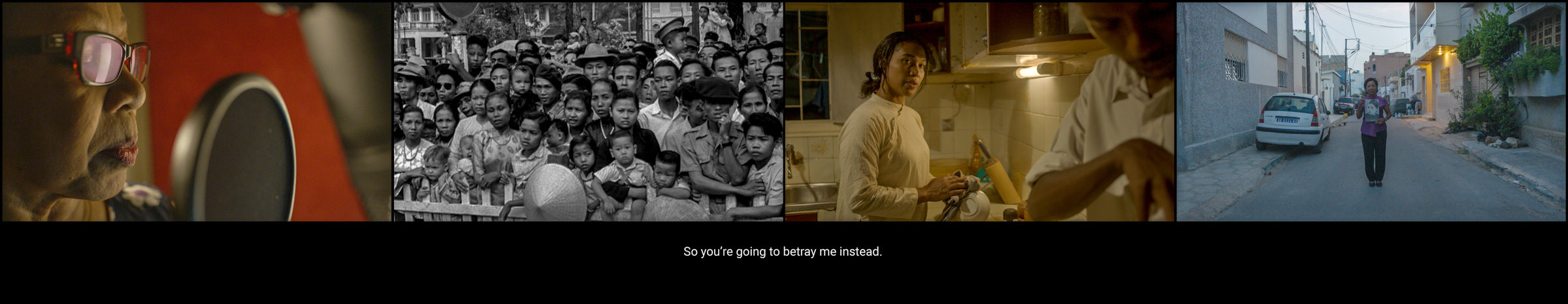

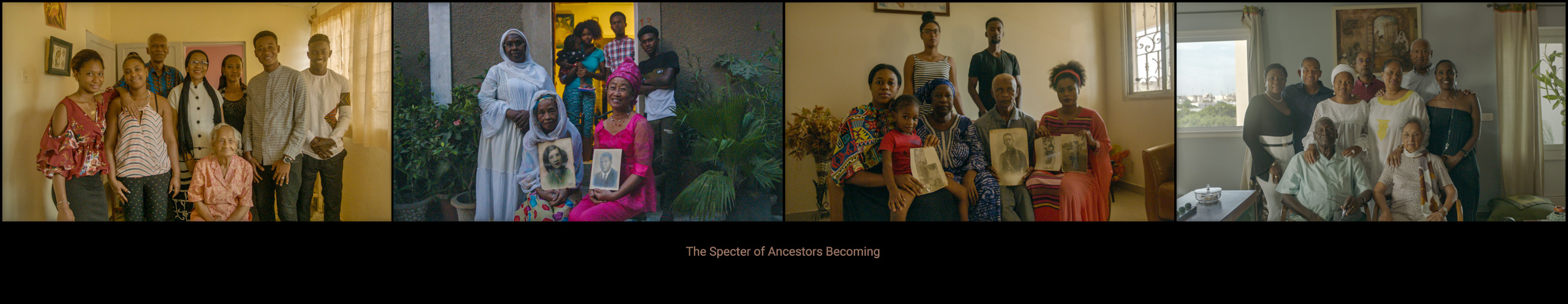

The Specter of Ancestors Becoming (2019) by Vietnamese artist Tuan Andrew Nguyen is a 4-channel video installation created for the Sharjah Biennial 14.[1] It deals with the Vietnamese community living in Dakar, Senegal, and in particular with the descendants of the Senegalese soldiers who took part in the Indochina War as part of the French colonial forces. Derived from the artist’s fieldwork in Dakar, and based on his collaboration with this Vietnamese-Senegalese community, the work highlights the persistence of colonial ghosts that still haunt and shape the present. The film features fictional narratives imagined by some of these now grown-up children, who try to reconstruct history and their personal past. It borrows its cinematographic language from the process of memory and unfolds in a non-linear way, including repetitions, archival images and fictional conversations. Ultimately, the film addresses the questions of identity and “métissage” and explores the issue of inherited individual and collective memory when it comes to transmit and remember a sensitive past.

Born in Ho Chi Minh City in 1976 but raised in the United States, Nguyen lives and works now in Vietnam. In 2006, he founded the art collective The Propeller Group which developed a critical approach of media and advertisement, and, in 2007, he co-founded Sàn Art, the most important independent art space in Vietnam. His multimedia practice revolves around constructed narratives and beliefs and examines how individual stories collide with history. His films often combine fiction with archival footage as a means to reflect on the entanglement of imaginative projections and historical memory.

Contextual framework and artists’ drive

A common yet ambiguous colonial past

Demba and Dupont. Monument to the Senegalese and French soldiers relocated in 2004 in the newly named Place du Tirailleur (Tirailleur’s square), Dakar.

(image from the Internet)

The “tirailleurs Sénégalais” (Senegalese troopers) was a French colonial army corps created in 1857 by Emperor Napoleon III. Despite its name, it did not include only Senegalese people but soldiers from all parts of French-occupied Africa. It was dissolved in 1960 when most of the colonized countries from French West Africa became independent, including Senegal which had been a French colony since the 19th century. These African soldiers participated in the two world wars but were also involved in the controversial French repression of anticolonial movements that arose after WWII, and in particular in Indochina. The Indochina War started in 1946 after the failure of the negotiations between Ho Chi Minh and the French authorities and ended with the French defeat at Diên Biên Phu in May 1954. Soon after the debacle, some African soldiers were sent to another major French colonial conflict in Algeria, where they had to fight on African soil, against enemies which were culturally closer.

“The first African soldiers arrived in Hanoi and Haiphong, in Tonkin in 1947. Sub- Saharan Africa served as the French army’s human reserve, as it had since 1914. By the time the cease- fire was in place, it had supplied 60,340 soldiers to the army. Almost 3,000 Africans perished in the war, 3,706 were wounded, and 2,546 were discharged due to illness.”[2] Historian Professor Ruth Ginio highlights how much unprepared were these soldiers who often arrived without a proper training. In order to boost their morale, French military authorities offered them so many decorations that this practice became perceived as ridiculous. In one archival footage from Nguyen’s film, one can see such a ceremony with the tirailleurs being decorated. In fact, many of them came back traumatized. However, the Senegalese tirailleurs had volunteered to join the army and go to Indochina. They were mainly driven by the possibility of a pilgrimage to Mecca, economic and financial reasons or by a search for social advancement.[3]

The Specter of Ancestors Becoming focuses on the descendants of these soldiers who came back to live in Senegal with their Vietnamese wives and/or children. It does not directly address their part of responsibility in the conflict nor the fact that they took side against forces that fought for decolonization. As recalled by Ginio, these tirailleurs were indeed fighting to defend “the same colonial rule under which they themselves lived.”[4] In the film, they are only depicted as soldiers working at the service of the French colonial authority, yet there is an underlying feeling of ambiguity that arises in a few dialogues, revealing how complex and equivocal this relationship with France was. In one scene in particular, which takes place in Saigon just after the French defeat between a tirailleur and his Vietnamese wife, the soldier says: “we lost the war” and immediately creates unease as to how this ‘we’ should be interpreted. In this context, the binary colonizer/colonized relations are thus much more complicated, leading to more confusion when it comes to define one’s identity. Three nationalities are mixed up: French, Vietnamese (from the South where people were fighting with the French against North Vietnam) and Senegalese, the latter two being the most important since none of these people were French, except, as one Senegalese soldier says in the film, when France needed them.[5] In the videos, however, all the interviewees speak in the French language, which points to the strong a heritage of colonization.

Hybrid identities and oblivion

For the Vietnamese women, the Senegalese tirailleurs represented money and protection and, although they were at first frightened by their culture and physical appearance, they were keen to establish relationships with some of them. On their parts, the soldiers “cater to her needs rather than go to prostitutes.”[6] Some married them and had children, whom they brought to Senegal after the war. Some left their wives in Vietnam and only came back with their children, while others brought children not their own. Ginio notes that some Vietnamese women sold their métis (half-breed) children to their African fathers.

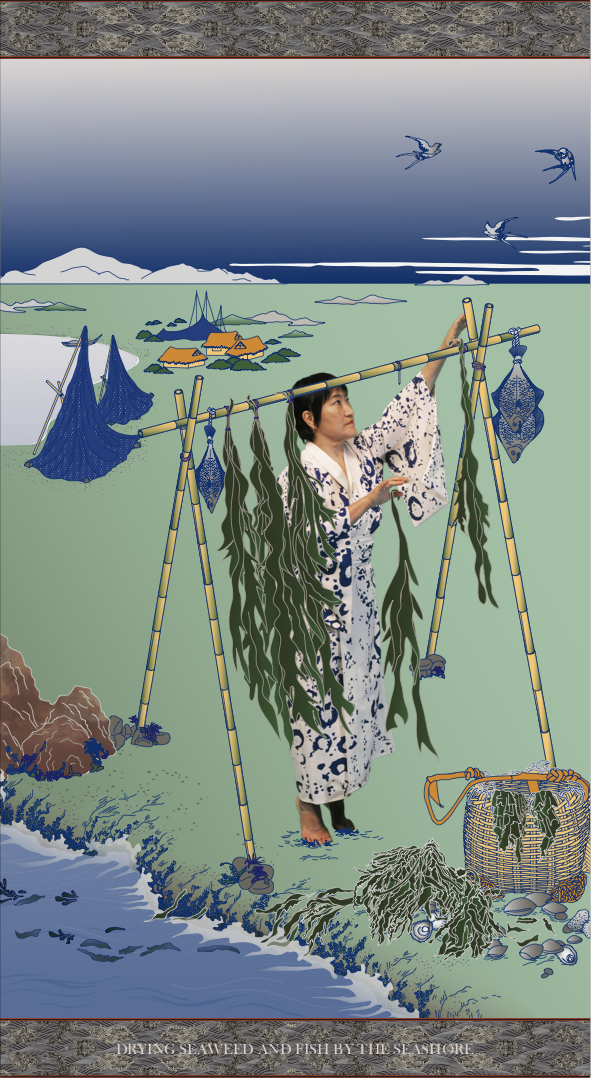

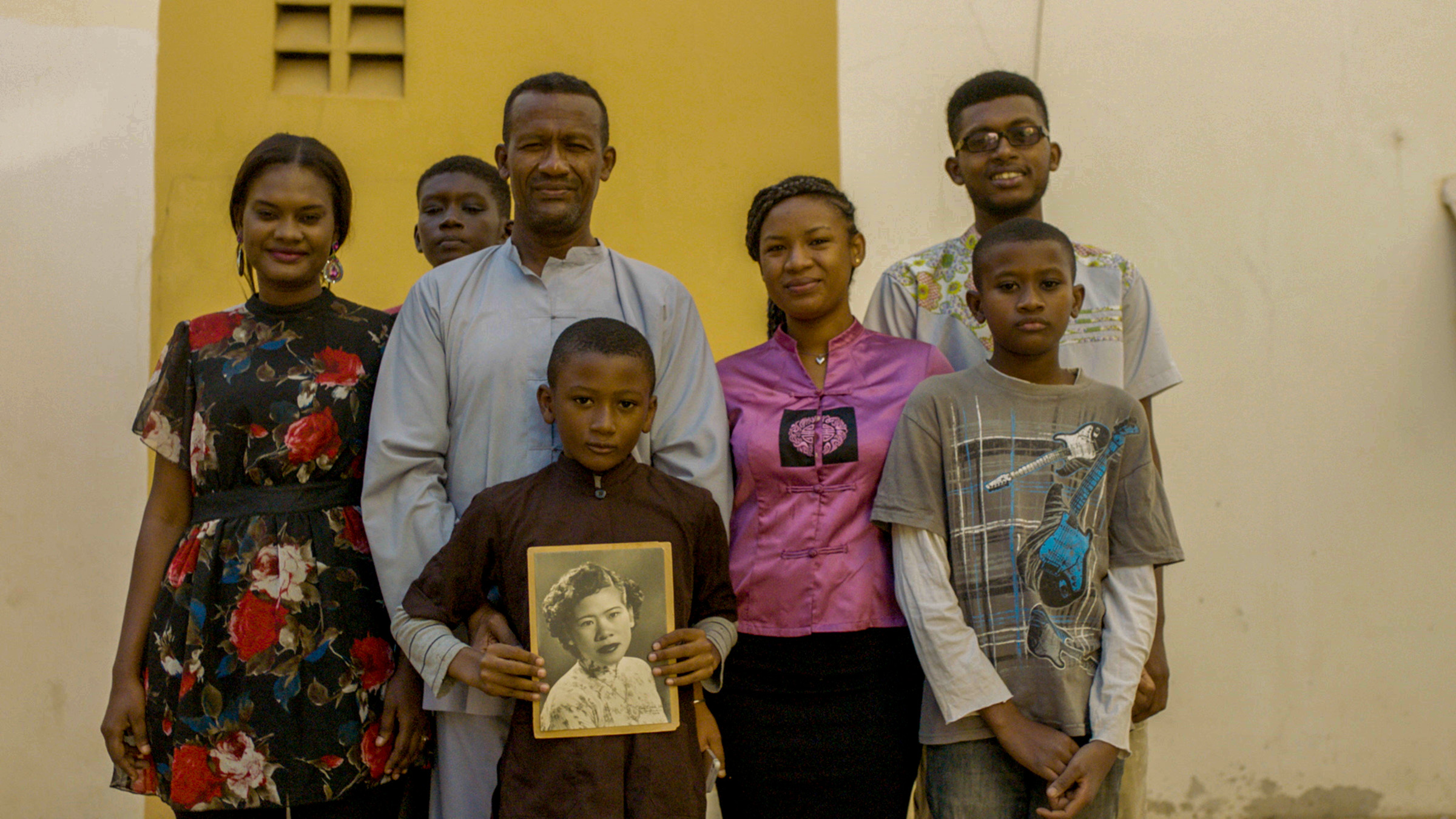

The Specter of Ancestors Becoming (2019). Still from the video (archival family portrait)

Professor of anthropology and historical studies Ann Stoler observes that the French were worried about métissage and notes how métis communities, or “mixed-race children,” were seen as a threat to the colonial order.[7] More generally, Stoler emphasizes how much intermariage threatens any kind of nation-state’s identity, with metis crisscrossing territories, customs, norms and boundaries. In Senegal, the arrival of these Vietnamese women and their métis children triggered a feeling of rejection. From his interviews with the Vietnamese community in Dakar, Nguyen discovered that many families were ashamed of them at that time. Some women were hidden, treated like foreigners or had to work hard to become accepted. However, many had no choice than to follow their husband: if they had remained in Vietnam, they would have been killed as traitors. They never returned there although some dreamt of doing so, and usually never talked about their native country. According to Bouba Diallo, a descendant of a Senegalese tirailleur interviewed by Nguyen, “when they left Vietnam, they were forgotten. They didn’t exist anymore.” Now that some of them already passed away, their children realize that they do not know who they really were and what was their story. They are left with a few letters or old black and white photographs and begin to question this part of the past that has fallen into oblivion. These women were in fact the pillars of their family and they wonder if they will have the ability to carry on what their mothers had initiated. For Nguyen, these questions of transmission are prominent: what does one need to remember and what does one have to forget?

Professor Marianne Hirsch coined for the first time the term of “postmemory” in the 1990s to describe children who grew up with inherited memories, and, in her case, memories from the Jewish Holocaust.[8] The concept can be applied for these descendants of Senegalese soldiers whose identity is shaped by a past they barely know. Some former soldiers never told their children about their origins, and these metis of Vietnamese descendance grew up feeling they were different yet they were unable to understand why. Macodou Ndiaye, interviewed by Nguyen, confesses for instance that he has lived for 19 years without even knowing he was a metis. He has two different birth certificates and for a long time his father denied his Vietnamese origin. These descendants of Senegalese tirailleurs developed different senses of identity according to their personal history. Aboubacar Sy aka Bouba Chinois, for example, has rejected the Senegalese nationality because his Senegalese father abandoned his Vietnamese mother with her 8 children. Lily Bayoumy, who only discovered that she was an adopted child found on the battlefield in Diên Biên Phu when her ‘parents’ died in 1988, feels more African because she received an African education. In the film, one of the characters proudly sings the national anthem of South Vietnam known as “Call to the Citizens” or “March of the Youths,” calling to “destroy invaders, liberate Vietnam…” This song disappeared from Vietnam after the fall of Saigon in 1975, when South Vietnam was annexed by the Viet Cong, yet it is still used by Vietnamese expatriates. In Dakar, it might sound unexpected for the local population.

The Specter of Ancestors Becoming (2019). Still from the video (singing the Vietnamese anthem)

There are about 3,000 people of Vietnamese origin living today in Senegal. They are in fact organized and some of them established the Association of Indochinese Vietnamese in Senegal, named Kim Hoi, in 2016.[9] The stories of the descendants of the Senegalese tirailleurs are not taboo but they belong to a part of history that tends to be neglected. In Dakar, some features of the Vietnamese culture have actually penetrated the local culture, such as typical Vietnamese dish (special fried rolls for instance) and martial art, but for the population, the connection with the history of this community has not been established. In the academic field, Ruth Ginio notes that “the focus of both public remembrance and academic research is on the soldiers’ roles during the two world wars rather than on their participation in France’s controversial wars of decolonization.”[10] For Stoler, France has not yet acknowledged its “racialized history” either, and the consequences of its colonial history continue to haunt the present.[11] Nguyen’s title precisely refers to these vivid ghosts as well as to the spirits from the past who are common in the Vietnamese culture. For the artist, who also works on the issue of the Vietnamese Boat People,[12] it is essential to question historiography but also how history is felt, transmitted and remembered. Fascinated by the stories he collected in Dakar, he wished to reflect on these processes of memory, their complexity, their impact and their gaps. “My individual practice is invested in exploring the limits of narrative: both the power of storytelling and its abuses.”[13]

The artist researcher

An open-ended approach

The Specter of Ancestors Becoming (2019). Still from the video (family portrait)

What Nguyen likes with research is that it does not necessarily lead him where expected and can unfold into a very different journey. Originally, the artist’s research was in fact not focusing on this metis community from Dakar and this artwork is a good example of this kind of fruitful bifurcation.

Nguyen’s primal idea was to research a form of solidarity that would have bound different colonized people, creating south to south relationships. In particular, for about a year, he has been searching for movements that would have linked the Senegalese tirailleurs with Indochinese fighters during the world wars. With his research assistant Jane Pujol, he has been seeking evidence for such a link within the French military archives, yet he could not find any. The soldiers from different origins were usually separated and formed different communities that never mixed up. In Dakar, he visited the Military Museum that opened in 1997 to document and record former soldiers’ testimonies,[14] and he interviewed veterans from the war. However, there were no traces of such a solidarity, and these soldiers were on the contrary proud to have fought on the side of the French. Hence, according to Nguyen, this research project was a “failure,” yet his fieldwork opened unexpected doors: as he was in Dakar, he met the Vietnamese community living there and became fascinated by their stories. He knew that there were Vietnamese people living in Africa but did not know about the descendants of the Senegalese tirailleurs. He thus chose to change his research topic and dedicated his work to their testimonies.

In total, Nguyen spent 8 days in Dakar during his first trip, meeting and interviewing people, and then came back for 3 weeks to shoot the film. He confesses this fieldwork was too short and he wished he could have stayed longer, but he managed to create a trusty and long-standing relationship with the community. In order to meet the tirailleurs’ descendants, he collaborated with Raw Material Company, an art space similar to Sàn Art, funded by Cameroonian-born curator Koyo Kouoh. The team introduced him to the Vietnamese community, which is actually located in the neighborhood of the art space. Nguyen’s approach to the interviewees was very open: usually he would ask them to tell their story the way they wish and he recorded the interviews. He collected thus hours of documentation that served as a base for his project but that he did not used directly. Above all, this first approach allowed him to better understand the context and concerns of these people and to give them a voice. The more he met people, the more he was introduced to new families since, in fact, everybody knew someone from a Vietnamese origin.

Sharing memory: documentary photograph from the artist’s fieldwork.

In parallel to this fieldwork, Nguyen continued to search for archival material pertaining to the participation of the Senegalese tirailleurs in the Indochina war. He notably collected footage from the Internet and photographs from the French “Établissement de communication et de production audiovisuelle de la Défense” (ECPAD) which records all images from the wars involving French armies, as well as from Anom (Archives Nationale d’Outre-Mer), the most important site for archives dealing with the French colonies established in Aix-en-Provence, France. This archival material functions as a set of evidence that supports the narratives collected by the artist during his fieldwork and grounds them within history. However, unlike the historian who would have linked these documents to the collected testimonies, Nguyen does not create any direct connection between them: on the contrary, he only juxtaposes these different modes of narratives and different approaches of the past. From official images to family photographs, recollections heard from relatives or memories kept within one’s heart, the artist plays with various forms of recording and transmitting history without questioning their legitimacy nor their coherence.

A collaborative process

“Every culture has a right and a responsibility to present its own culture to its own people. That responsibility is so fundamental it cannot be left in the hands of outsiders, nor be usurped by them.”[15] To give public exposure to a community to which one does not belong is not an easy task, as Maori filmmaker Barry Barclay reminds us in this quote. In 1982, Vietnamese filmmaker and theorist Trinh T. Minh-Ha shot also a film in Senegal, entitled Reassemblage. This famous documentary film features rural villagers and questions the possibility of representing a culture as an outsider. Minh-Ha suggests to “speak nearby” the community she describes,[16] a process involving “a speaking that does not objectify, does not point to an object as if it is distant from the speaking subject or absent from the speaking place. A speaking that reflects on itself and can come very close to a subject without, however, seizing or claiming it.”[17]

Nguyen does not pretend to describe the culture and customs of this specific community but only to highlight the complexities and difficulties to bear the weight of an inherited past. His practice focuses on the process of memory, remembering and forgetting, and does not involve a systematic observation of the life of the descendants of the Senegalese tirailleurs from Dakar. However, his film gives them a voice and, although he did not stay long enough to deeply engage with this community, his bottom-up approach resembles the practice of an ethnographer collecting first hand testimonies in order to reflect on the specificities of a peculiar community. To avoid claiming, appropriating or objectifying the stories of these Senegalese-Vietnamese, yet to remain close enough to them, Nguyen chose to collaborate deeply with some members of the community so that they would be the ones who present their own history. Furthermore, he proposed to some of them to write fictional scripts that would relate to their stories, and to perform them.

The Specter of Ancestors Becoming (2019). Still from the video (father and son, 4 screens)

Nguyen has often used fiction as a way to fill the gaps in history and to compensate for the lack of archives, in particular when he worked on the topic of the boat people. In Dakar, the idea of intertwining fiction and reality emerged when he discovered that one of the women he interviewed, Anne-Marie Niane, had written a short novel about her Vietnamese mother, telling her story when she arrived in Senegal and had to face such cultural gaps as polygamy.[18] From this novel, Nguyen proposed her to develop her fictional narrative and to invite other members of the community to join the process. Nguyen did not drive their discussions nor their approach to the topic: inspired by their personal stories, Niane wrote a fictional scene taking place in the past in Saigon featuring a tirailleur and his Vietnamese wife when he had to leave Vietnam; Macodou Ndiaye related the confrontation between a father and his son in Dakar during which the son reproaches his father to have hidden the truth about his Vietnamese origins. Finally, Merry Bèye Diouf imagined a dialogue between a young Senegalese woman and her Vietnamese grandmother. Altogether, they spent time in meetings and debates so that the sequences reflect the community’s participation and engagement. For Anne-Marie Niane, writing the screenplay was a way to reconstruct history. “Where memory fails, imagination does the rest.” In an unpublished interview with the artist, she insists on the positive effects of the experience: “we can rebuild a life by rebuilding a story.”[19] The Specter of Ancestors Becoming features these three fictional scenes together with additional extracts from the artist’s interviews and archival materials. Ultimately, all the scenes are staged and the characters from the film are either acting or are at least aware of the presence of the camera. The artist never appears in the film and, for the interviews, the interviewer is always absent.

Hence, Nguyen never speaks on behalf of these descendants but lets them speak through the archives, their family photographs, their testimonies and the fictional stories they wrote. As we will see, his staging and editing choices are obviously personal but, throughout his collaborative research process, he remains “nearby” and does not appropriate the culture and history of this particular community. Implicitly, he rather attempts to “make the camera a listener,” an objective praised by Barry Barclay when he questions the ideal attitude of a filmmaker working with an indigenous community.[20]

Artistic transformations of the research findings

Multivocality and hybridity

The Specter of Ancestors Becoming consists of several chapters of unequal length that are juxtaposed without any causal links. They do not form a linear narrative, although Nguyen arranges them to create a beginning and an end. The film is displayed simultaneously in four screens that were, in Sharjah, facing each other around a large circle where viewers were invited to sit. The four images complete and dialogue with each other, offering at all times a plurality of perspectives through various modes of expression.

The film starts with a non-fictional scene featuring a man, whose name is not mentioned, filmed in his living room in Dakar. He tells his story from a letter written by his Vietnamese mother to his father when she was pregnant with him, in 1956. At that time, his father had already left Indochina, while his mother remained in Saigon. While he reads, archival images pop up on the other screens, close-up shots of the letter but also photographs featuring his father (an African soldier in uniform) and mother (dressed in traditional Vietnamese clothes). For the artist, this letter constituted a relevant point of departure to set up the context and engage the viewers.

The Specter of Ancestors Becoming (2019). Still from the video (Saigon script, 4 screens)

After a sharp cut, the following sequence is introduced by a soft yet slightly dramatic music. A woman reads a script in a microphone, including dialogues and stage directions: “Interior. Apartment, Saigon. Night.” On the other screen, a play is acted, featuring a “Vietnamese woman in her late 20’s,” and Waly, “a tall, dark man.” They are arguing about leaving Vietnam and we understand this is the end of the French colonial rule. Archival photographs, mainly from the war, punctuate the scene and are displayed on the other screens. For instance, there is a short film showing the French flag being pulled down, as a representation of the French defeat. Among these black and white images from the past, the narrator is filmed, immobile and holding the portrait of a young lady.

The transition to the next sequence is again made by music. This time, the interviewee is singing the national anthem of South Vietnam in his apartment. We can hear him sing first against the backdrop of an archival film featuring children following a military ceremony during which a French commandant is giving medals to African soldiers. The film then includes two more fictional and staged scenes involving an outside narrator, combined with past and contemporary images from the community. It ends with a musical sequence featuring a young singer dressed in traditional Senegalese clothes who sings in Wolof, a Senegalese language: “don’t be lazy, don’t give up. Don’t deny, don’t abandon.” The musical composition was in fact already played during transitions, yet without words. The last scene resembles a music clip, with images shot in slow motions. It shows daily moments of the local life with a dominance of portraits from all the people of the community. The final images are family portraits with some of the members holding photographs of their ancestors. The singer, Ousmane Serigne Mbacke Noreyni Seck embodies the new generation, in contrast with the former general who sings the Vietnamese anthem. For the artist, it was important to end the film with a perspective open to the future and, with the family portraits, to change scale from an individual to a collective level.

The Specter of Ancestors Becoming (2019). Still from the video (practicing martial arts)

Hence, the structure of the film remains very open. As with metissage, the work disengages itself from a linear and single use of language and constantly blurs the boundaries of styles: it presents a hybrid juxtaposition of voices and personal narratives in which reality and fiction overlap seamlessly. There is no hierarchy nor principle of organization that would guide this plurality of testimonies. The black and white archival images complement the narratives without explaining them. Besides, the artist included mute scenes of people from the community practicing martial arts and tai chi, a legacy of their native culture which is now transmitted from father to son. The modes of expression are thus very diverse: personal verbal recollection, songs, silent images and written scripts. It is only the music that links these various scenes, with Noreyni’s song representing a link between these scattered pieces of individual and collective memory, absences and presences, dreamlike and factual realities, opening up new possibilities to (re)define this community beyond their inherited past.

Fragmented flows of memory

The structure of the film seems in fact to follow the logic of memory, involving ruptures, contradictions, flashbacks and a constellation of different times and places that overlap and respond the ones with each other. This simultaneity is made possible by the four screens of the installation but is also suggested by the artist’s editing process that allows a superposition of time and perspectives. In cinematographic language, there is no past, no present, no future but an artificial time-line that can be endlessly reactivated. In the first fictional scene, for example, the narrator is the daughter of the couple who argues about leaving Vietnam. Since the script is taking place in the past, she is older than her own mother. She is also speaking on the behalf of her father and mother, and the synchronization gap between her monochord voice and their own lips creates a distance such as that one can feel when dreaming or remembering. Memory reorganizes time and reminiscences in very personal ways that are sometimes unexpected, with specific souvenirs emerging abruptly or coming back repetitively. In the film, some images or short sequences are coming back, and some sentences are repeated as if they were forming a loop. Close-up shots on objects reflect also memory’s attachment to details and how much souvenirs can be triggered by a simple gesture (for instance, here, combing hairs) or mundane items. Recollection can be either clear or blurry, just like floating souvenirs, and most of the scenes are actually filmed in slow motion with the fictional sequences ending with blurry images. Furthermore, long camera travelling seem to mimic a wandering mind. The characters who are filmed holding their family portraits are for instance usually immobile, yet the camera glides closer to them until it goes back again, perhaps to leave the past behind.

The last fictional scene refers directly to French director Alain Resnais, who is famous for addressing the issue of memory and for including archival images in his films. In particular, the dialogue between the young lady and her grandmother borrows the phrasing and rhythm from Resnais’ film Hiroshima My Love, when the French woman questions her Japanese lover about Hiroshima.[21] He states that she has seen nothing at Hiroshima; she replies that she saw all although she was not present during the explosion. In The Specter of Ancestors Becoming, the young Senegalese girl combs her grand-mother’s hair and also questions her about a past and a place she does not know: “Do you remember? I remember. What do you remember? (…) I remember everything about Indochina. You remember nothing of Indochina. You saw nothing of Indochina.” The narrator mixes the replies and creates a confusion about who speaks. It is not anymore about what is remembered but about how it is remembered, and by whom. “Like you, I know oblivion. I am capable of memory. Like you, I have forgotten,” says the French woman in Resnais’ film. Here, oblivion and memory form an inseparable couple. Time washes out everything and the 90-year old Vietnamese grand-mother is about to die, yet her grand-daughter asserts that she wants to remember. Why would we need so hard to remember, especially a past that does not belong to us?

The Specter of Ancestors Becoming (2019). Still from the video (I remember)

For Friedrich Nietzsche, human beings keep remembering the past and often bend under the weight of the burden it represents. In contrast, animals look happier, for they live “unhistorically.” The German philosopher does not invite human beings to imitate the animals but questions their excess in trying to hold on to the past and cultivate historical knowledge. As such, he praises the benefits of oblivion, that can sometimes be healthy and necessary. In Hiroshima My Love, the French woman confesses that, in the end, she will forget her lover, who “will become a song”. Perhaps the postmemories that weight in on the descendants of the Senegalese tirailleurs will transform into Noreyni’s song that closes Nguyen’s film.

Intimacy and compassion

The dialogue between the grandmother and the girl, who is also the narrator, is full of love and mutual understanding. While she combs her hair, images featuring different generations of women, embracing each other or holding each other tight are displayed on the other screens. All their gestures are gentle and follow the slow and diligent movement of the comb. In general, there is no violence and no traces of open conflict in the film. Even the dispute between the father and his son ends with a reconciliation. Despite bearing the weight of complicated stories and lies, the people filmed by Nguyen seem to cope and, in any case, never accuse anyone for their heritage. Again, most of the scenes are filmed slowly, some in slow-motion, and the movements of the camera are always soft. In the first scene, while Macodou reads his letter, it even seems that the camera tries to wrap him up as if to comfort him. The man reads very slowly this unique letter from his Vietnamese mother, stumbling over the words which are ill-written and because he often needs to correct his mother’s French. The scene is very moving, and the artist gives time to the viewer to feel this emotion.

Most of the interviewees stare at the camera, thus at the viewers who seem to participate in Nguyen’s investigative process. Together with the artist, they also become spectators of the staged scenes written by these people and share these moments of intimacy. In Sharjah, the video installation was set outdoor and the floor was covered with sand, which accumulated at the foot of the four walls supporting the screens. The public sat or stood in the middle of the installation, surrounded by images and sound. There was nothing around, except the large sky above and the city far away. This setting created an immersive experience favoring empathy and aptly echoed the passing of time.

The Specter of Ancestors Becoming (2019). Still from the video (duo portraits)

When discussing The Boat People (2020), which deals also with memory yet from a very different perspective, the artist emphasized the need for compassion when it comes to history: “I don't subscribe to the idea that repair is an option within a post-colonial context, where so much has been decimated historically; but I do think shared compassion is an immensely useful tool, philosophically and in practice. It is completely constructive, without being victim to the past, and without being subservient to the future. Hence, I believe that shared compassion is empowering.”[22]

Nguyen’s emotional style is clear from the start: when the title of the film appears on a dark background, some shadows grow inside the letters while a dramatic music sets the tone. The feeling of empathy is strong throughout the work, with close-ups on faces and direct eye contacts with the interviewees who seem to share their stories and dearest photographs with the viewers. When the characters stare at the camera, they look also deep inside themselves and expose their intimacy. The photographs they hold are more than photographs. As explains professor Marianne Hirsch when addressing the issue of postmemory: “more than oral or written narratives, photographic images that survive massive destruction and outlive their subjects, function as ghostly revenants from an irretrievably lost past world. Photographs, analog photographs, in particular are evidence of past presence. They have an indexical relationship to the object that was before the lens. But they also quickly acquire symbolic significance and thus they are more than themselves.”[23] However, as they are presented in the film, these ghosts seem today benevolent. Nguyen’s editing choices and style highlight how much these people are now proud of a heritage that they have learnt to accept serenely. We are thus far from Ann Stoler’s specters of “colonial toxicities” that haunt the present,[24] or from the specters described by T.J. Demos when he analyses the photography and film works of a few artists focusing on postcolonial Africa.[25] The Specter of Ancestors Becoming does not deal with the current social, political and economic impacts and traces of the French colonization in Senegal but focuses on personal, intimate scars. The descendants of the Senegalese tirailleurs, as perceived in the film, do not seem to be marginalized but the question of their integration within today’s Senegalese society is not addressed. As suggested by the title and the idea of “becoming,” the film is rather turned towards an open future that would acknowledge the past without being hindered by it.

Conclusion

The Specter of Ancestors Becoming (2019). Still from the video (family portraits, 4 screens)

For The Specter of Ancestors Becoming, Nguyen combined different research methodologies, mixing archival research with a collaborative and bottom-up perspective of history. He entangled collected oral testimonies with reconstructive, thus fictional, individual stories and based his fieldwork on a dynamic and dialogic approach. The 28-minute-long film is the outcome of these sound and visual ‘collages’ that reflect this multivocality. It creates a critical space for a an emotional, aesthetic, yet rational, knowledge to arise about this particular community, whose identity and history have been hitherto neglected. Although the narratives are fragmented and sometimes confusing, the sensitive issue of memory, its difficult and problematic transmission as well as the burden it represents are induced by this constellation of forms, silences, confessions, projections and reminiscences. The viewers are guided by the script, yet they remain free to develop their own imagination: the contextual background is, in fact, barely mentioned with the given factual elements referring to very specific cases and testimonies. As such, there are still many gaps that the film does not fill, yet it precisely triggers curiosity and the desire to know more. In particular, the life conditions of these Vietnamese immigrant women are not exposed, nor the tensions that must have arisen between the soldiers who returned from the colonial wars and the local people. We do not know either how these descendants are living, what is their social status, what constitute their aspirations and what did they really inherited from their peculiar identity, except martial art. In the film, one can only grasp a few clues, yet without having a general picture of what happened and of who they are.

Hence, The Specter of Ancestors Becoming offers a relevant example of a kind of post-documentary aesthetics in which the poetics of language dominates fragmented and singular pieces of information. The knowledge it generates remains indeed open-ended, implicit and above all partial with the artist focusing on individual affect and emotional sensitivity. It nevertheless constitutes a first step towards a better understanding of the French opaque colonial heritage and its long-lasting consequences on the Senegalese society. More specifically, it points to the multi-layered flux of migrations caused by colonization, and how they reshuffled national identities.

[1] SB14: Leaving the Echo Chamber, curated by Zoe Butt, Omar Kholeif and Claire Tancons, from 7 March – 10 June 2019, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates.

[2] Ginio Ruth, The French Army and Its African Soldiers (University of Nebraska Press, 2017), 86.

[3] More on the Senegalese tirailleurs, see also Julien Masson’s 2015 documentary film Memoire en marche (Memory in movement).

[4] Ginio Ruth, The French Army and Its African Soldiers (University of Nebraska Press, 2017), 78.

[5] In the film, the character who plays a soldier in Vietnam states: “I am French only when they need someone to take bullets.”

[6] Ginio Ruth, The French Army and Its African Soldiers (University of Nebraska Press, 2017), 96-97.

[7] See Stoler Ann, “Sexual Affronts and Racial Frontiers: European Identities and the Cultural Politics of Exclusions in Colonial Southeast Asia,” Comparative Studies in Society and History, Vol 34 issue 3, July 1992: 514-551.

[8] Hirsch Marianne, The Generation of Postmemory (Columbia University Press, 2012).

[9] More of this association, see for example the article online: https://en.dangcongsan.vn/overseas-vietnamese/about-3-000-vietnamese-people-live-in-senegal-434795.html

[10] Ginio Ruth, The French Army and Its African Soldiers (University of Nebraska Press, 2017), xx.

[11] Stoler Ann Laura, “Colonial toxicities in a recursive mode,” Postcolonial Studies, 21:4 (2018): 542-547.

[12] See for example Nguyen’s film The Island (2017) and recently the single-channel video The Boat People (2020).

[13] Tuan Andrew Nguyen in conversation with Vivian Chui, “Tuan Andrew Nguyen: The Limits of Narrative,” Ocula magazine online, 17 April 2020.: https://ocula.com/magazine/conversations/tuan-andrew-nguyen/

[14] “Musee des Forces Armees,” in Dakar. See their online website:

https://www.museomix.org/en//editions/2018/dakar-musee-des-forces-armees

[15] Barclay, Barry. Our Own Image: A Story of a Maori Filmmaker, University of Minnesota Press, 2015: 7.

[16] In the film, the voice over says: “I do not intent to speak about, just to speak nearby.”

[17] Chen Nancy, “Speaking Nearby”: A Conversation with Trinh T. Minh-Ha,” Visual Anthropology Review Vol 8 (1) (1992): 87.

[18] The book was published in French language. See Niane Anne-Marie, L’Etrangère (Paris: Hatier, 1984).

[19] Quotes from Nguyen’s non-edited interviews, courtesy of the artist.

[20] Barclay, Barry. Our Own Image: A Story of a Maori Filmmaker, University of Minnesota Press, 2015: 17.

[21] Hiroshima Mon amour / My Love, 1959 movie by Alain Resnais, screenplay by Marguerite Duras.

[22] In conversation with Vivian Chui, “Tuan Andrew Nguyen: The Limits of Narrative,” Ocula magazine online, 17 April 2020.: https://ocula.com/magazine/conversations/tuan-andrew-nguyen/

[23] Interview online with Marianne Hirsch (https://cup.columbia.edu/author-interviews/hirsch-generation-postmemory )

[24] Stoler Ann Laura, “Colonial toxicities in a recursive mode,” Postcolonial Studies, 21:4 (2018): 542-547.

[25] These artists are Sven Augustijnen, Vincent Meessens, Zarina Bhimji, Renzo Martens and Pieter Hugo. Demos T. J., Return to the Postcolony. Specters of Colonialism in Contemporary Art (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2013).