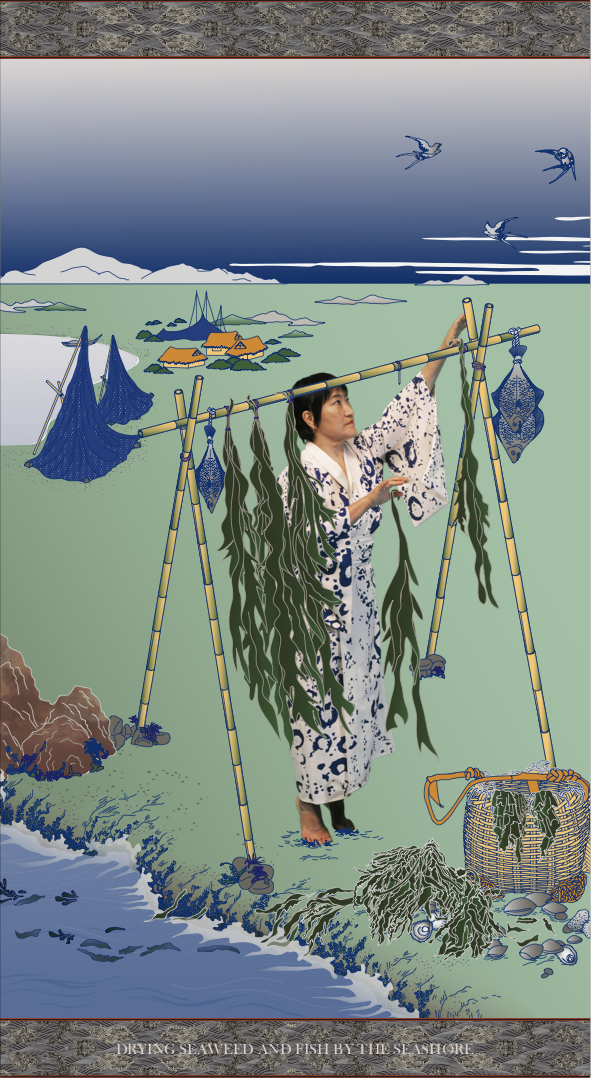

Image: Kris Project I: The Never Ending Tale of Maria, Tin Mine, Spices and the Harimau

Installation view installation view, Fotoaura Institute of Photography in Tainan, Taiwan (2017).

All images courtesy of the artist.

Kris Project I: The Never Ending Tale of Maria, Tin Mine, Spices and the Harimau is a video installation by Malaysian artist Au Sow Yee. The 15-minute film tells the story of Maria, the daughter of a Sultan from the early age of history who lived in a fictional place called Mengkerang. During her long journey across the wild rain forest up to the mythical country of Lanka, she evolves and transforms as she encounters various spirits and hybrid creatures. In the end, her body transmutes into an island and a piece of the ocean while she becomes the new sultan of Mengkerang. Inspired by local folk tales and by the colonial history of Malaysia, the artist weaves together archival footage, songs and contemporary images to propose an original portray of her native country and of its plural identity.

Born in 1978 in Kuala Lumpur, Au studied in Taiwan and in the United States. An experimental filmmaker, she delves into various mediums and performative artforms. The Never Ending Tale is the first part of her Kris Project (2016-2020), a trilogy of research-based video installations dealing with the emergence of Malaysia as an independent nation during the Cold War.[1] The project features a fictional filmmaker named Ravi who uses his collection of archives, including British news and footage from the film industries from the golden age of Malaysian cinema to create his personal movies. His collection of documents is displayed alongside the works.

The Never Ending Tale is thus embedded in a fictional framework although it focuses on a very specific, real-life time period when Malaysia emerged as a new country and was thus in search for the foundations of its new unity and identity. Au’s artwork displays a complex network of interconnected references, but the real power of the film lies in its ability to remain on the edge of reality and to plunge viewers into an ambiguous and poetic universe where everything keeps mutating. The knowledge it conveys is therefore open, ambivalent and fragmented, inviting us to reflect critically on the genesis and representation of any national identity.

Contextual framework and artists’ drive

Melayu, Malaya and Malaysian identity: a complex notion

The Never Ending Tale takes place in Mengkerang, a fictional country where people of different ethnicities peacefully coexist. Au invented this territory in 2013 when she created A Day Without Sun in Mengkerang, a video featuring a series of interviews during which the artist asked people from different ethnic communities to describe an imaginary place called Mengkerang. At that time, the debate about the Malay identity and the multi-ethnicity of its population had been strongly reactivated with the general election. Despite a strong mobilisation for the opposition party, the right-wing Barisan Nasional party, in power since the country’s independence in 1957, was again victorious.[2] The resulting racial tensions and protests that arose reflected a deeper general concern about the nation’s identity that dates back to the country’s construction as an independent nation. The process of nation-building in Malaysia indeed encouraged the valorization of the Malay culture, with Islam as the national religion.[3] Over the years, and until today, the question was how to define Malayness and “who is a Malay”[4] among this pluri-ethnic population.

Image: Kris Project I: The Never Ending Tale of Maria, Tin Mine, Spices and the Harimau still image from the video (Hindu temple). Courtesy of the artist.

Malaysia is a young country, whose current borders date from 1965 when the separation with Singapore took place. Linguistic and archaeological research found that the Malay World, or Melayu, has been existing since the seventh century AD.[5] In pre-colonial times, the people known as Malay were living across different islands and territories between today’s Indonesia, the Philippines and the Malay Peninsula. With Malacca being the most important trade port of the region, the Malay language was the local lingua franca. The colonization imposed artificial borders to this very fluid culture, with each colonial empire dividing the zone into distinct countries ruled according to distinct policies. The Anglo- Dutch Treaty of London (1824) led to the constitution of British Malaya including the Malay Peninsula and Singapore. With their policy regarding the conduct of census, the British administration encouraged further divisions by valorizing ethnic categories and groups. Besides, colonial economic development produced a demographic shift with the recruitment of immigrant workers, mainly Chinese for the tin mining industry and Indian for the development of the rubber plantations, the two pillars of the colonial economy. After the independence, more immigrant workers came from Indonesia and the Philippines. Over time, inequalities between these different groups of people have widened, with the Malay people earning less than the other ones. After violent racial riots in 1969, and to redress inequalities, the government established an affirmative policy that favored the Malays over the Chinese and Indians, and encouraged the islamisation of the society.[6]

Today, although the young generation tends to define itself as Malaysian and not in regard to their ethnic belonging,[7] racial issues are still unsettled in Malaysia. With Mengkerang, her ideal territory, Au wish to point to a more inclusive conception of identity. Most of her artworks emphasize the fluidity and the porosity of cultures, religions and traditions. Against a homogeneous conception of Malayness based on specific markers of identity, and against this “intense politicization of religious differences,”[8] she would probably agree with Maznah Mohamad and Syed Muhd Khairudin Aljunied, who conceive Melayu “as a signifier that brings to mind a whole array of associations — places, languages, families, communities, nation-states, cultural symbols, events, texts, collectives, political parties and religious beliefs.” [9]

The construction of Malayness during the Cold War: the film and media industry

After World War II, and following the Japanese occupation of the territory, the British planned to restore their power over the Malayan region with the intention to eventually establish a self-governing nation. The Federation of Malay, founded in 1948, was a compromise with the newly formed party United Malays National Organization (UMNO), the predecessor of the Barisan Nasional party.[10] This plan did not include the independence of the country, and did not award citizenship to non-Malays.[11] Meanwhile, the British had rehabilitated their lucrative rubber and tin activities. In reaction, the Malayan Communist Party (MCP) started a 12-year long armed guerrilla struggle against the colonial rule, known as The Malayan Emergency. Most of the fighters were Chinese and non-Malay, and they were hiding in the jungle. To fight them, Britain sent Gerald Templer (1898-1979), who developed a counter-insurgency strategy that has been praised for its efficiency, although it implied the use of chemical weapons and some controversial violent actions.[12]

Image: Gerald Templer inspecting the members of Kinta Valley Home Guard in Perak.

Archival image found on the Internet.

Au Sow Yee’s Kris Project (2016 - 2020) focuses on these founding years of the new Malay-nation as they crystallize all the forces that continue to shape the country today. “I am interested in that period of history because of its ambiguity. Many of the issues of that time still resonate in today’s Malaysia and South East Asia.”[13] In particular, the series highlights how the media and the new local film industry have contributed to build a collective image of the country in the midst of the Cold-war political turmoil and identity quest. On the one hand, the colonial media depicted a homogeneous subjected population and, on the other hand, local films emphasized Malay aspirations.

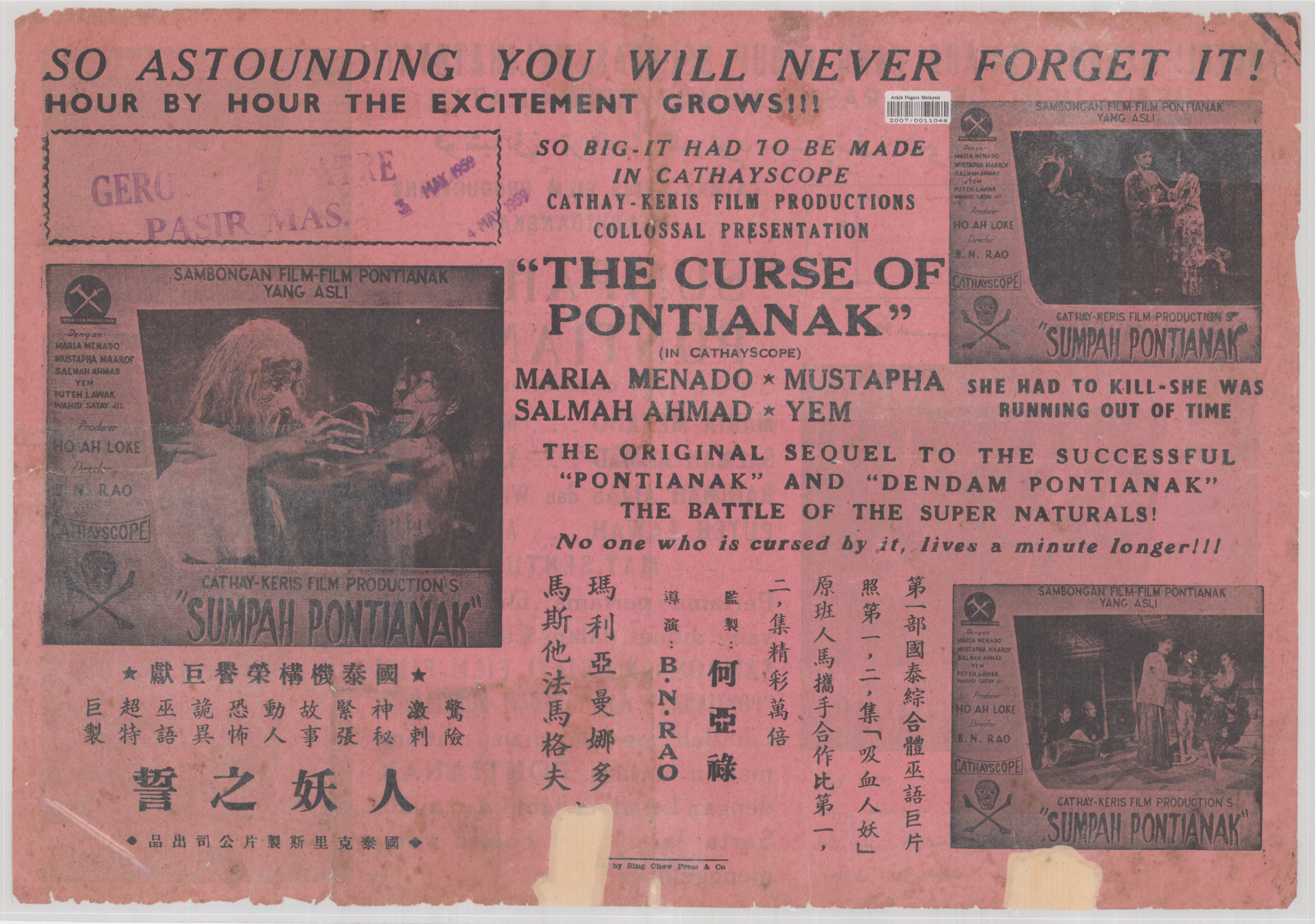

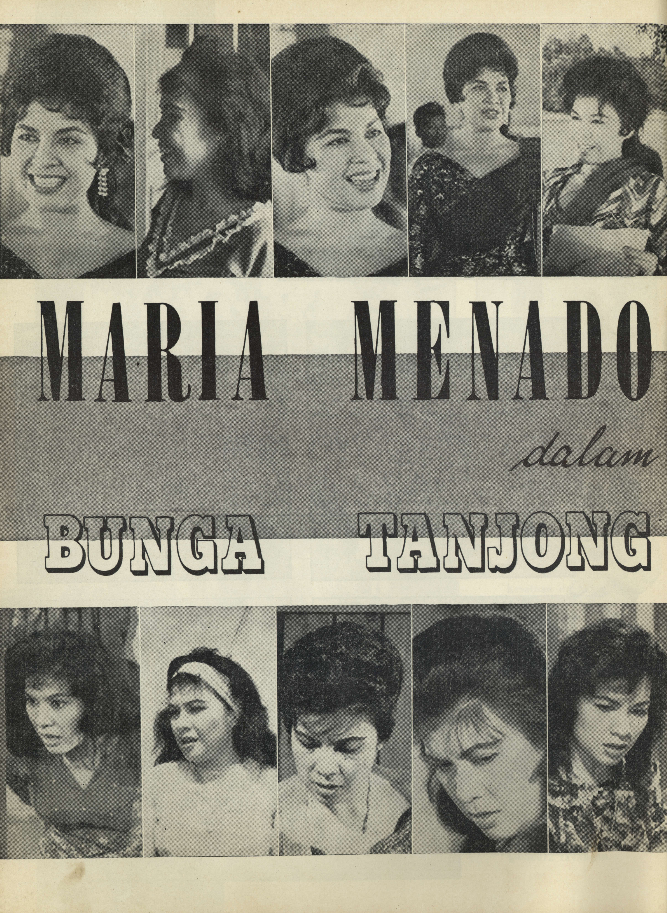

In Britain, for example, Pathe News and British News broadcasted exotic images of the country with British officers commanding obedient local workers and soldiers. Some films featured Gerald Templer supervising tin mining, greeting local villagers or inaugurating Malayan Railway, always smiling and in control. Locally, a Malay film industry developed from the 1950s with the Shaw Brothers and Cathay Keris Studio, after which the artist named her Kris Project series. The studio produced very popular Malay-language movies including ghost films such as Pontianak, a black and white series featuring iconic actress Maria Menado turned into a monstrous spirit. The figure of the Pontianak, who is a cursed single mother with a dead child and multiple bodies, could embody the difficulties of the country to engender an independent nation-state, yet most of the films made during this period did not defend any political views but were rather rooted in Malay traditions.[14] The Pontianak, for instance, might refer to pre-Islamic beliefs and shamanic rituals, combined with an indigenous culture of animism.

Image: Sumpah Pontianak, film poster

Archival image found on the Internet

During this golden age of cinema, the films were distributed in Hong Kong, Singapore and Malaysia, translated into Mandarin or Cantonese, and could be directed by Filipino directors.[15] As such, they were reflecting a certain trans-cultural conception of the region. Maria Menado, was for instance born in Indonesia and iconic singer Grace Chang, who opens The Never Ending Tale and who acted in films produced by Cathay’s Hong Kong studio, was born in China. She was the idol of the artist’s mother and Au remembers watching her films during her childhood in Malaysia within their Mandarin-speaking community.[16] She incarnated cosmopolitanism and her song and dance performances, because they combined various filmic genres, embodied the crossing of cultural boundaries.[17]

Revealing hidden stories

The idealized British news films were obviously helping the colonial propaganda to justify Britain’s military effort during The Malaysia Emergency. Similarly, Au wishes to point to the hidden stories behind the glamorous Malay films. “I am really interested in what is not visible. I try to play with this idea of the invisibility of the images and how images are constructed in our conscious mind through the work. (…) If you look at the old Hong Kong movies from the Cathay Organisation, (…) they really want to convince you of something, but my interest is to give you some clues that it is actually something else.”[18]

Malay cinema is not easily defined as it involved complex cross-cultural influences.[19] The artist does not clarify what the film industry wished to convince the viewers about, nor how it promoted a national unity or moral order during the nation’s early days, but her chosen footage refer to the Golden Age of Malay Cinema that lasted until the end of the 1960s during a period that also preceded what has been called the “Islamic resurgence” in Malaysia. [20] Progressively, the government institutionalized Islam as the dominant religion of the country, and some elements of its multi-ethnic culture disappeared or were censored. Many indigenous beliefs like shamanism and Sufism, or the practice of the bomoh, which features in The Never Ending Tale, became suspicious and considered as deviant from the Islamic faith.[21] All but one Pontianak films, whose footage are also included in the film, were banned then destroyed when Maria Menado married the late Sultan Abu Bakar in 1963. According to the artist, the genre of Malaysian fantasy movies did not survive this Islamization trend either.

At the same time, with the domination of the Malay Islamic culture, some ancient Hindu-Buddhist traditions have been marginalized, although they played an important role in shaping today’s Malaysian identity. While the Indian community tends to be discriminated,[22] Au implicitly highlights the importance of the Indian culture in The Never Ending Tale. Hindi films had also a great influence in the development of Malay melodrama cinema.[23] One part of the film’s story takes place in Lanka, which is known as the kingdom of Ravana, a demon King who kidnapped the wife of Rama, the hero of the Ramayana. A pillar of the Hindu tradition, this ancient Sanskrit tale is pervasive in all the Southeast Asian region and there are various local versions of the epic, including a Malay one. The narrative also relates the heroin’s fourteen-year exile to the forest which could refer to both Rama own’s exile and to the exile of the Pandava brothers in the other Indian traditional epic, the Mahabharata.

“I have always wanted to open up renewed paths for knowledge production and transmission. There is always a vertical line aside the horizontal one, especially with memory which can move in fluid manners or jump around.”[24] Ultimately, The Never Ending Tale weaves and deconstruct various traditions, beliefs and stories in order to break from any homogeneous conception of the Malay identity and from any dominant and linear forms of historiography.

The artist researcher

Collecting and connecting archives

Images: Maria Menado poster and cartel

Archival image belonging to Ravi’s collection and displayed in the installation

Courtesy of the artist

Au defines herself as a storyteller and as a story collector. Most of her research process involves investigating and collecting archives. For the Kris Project series, the departure point of her research was the death of Loke Wan Tho, the Malaysian businessman who founded Cathay Organisation and Motion Picture and General Investments Limited (MP&GI). He died in a plane crash in Taiwan after attending the Asian Film Festival in 1964. From this event, the artist began collecting books, magazines and archival images dealing with the film industry and, progressively, with the Cold War period in the region. She searched for film archives in Taipei, in the Malaysia National Archives and in Singapore archives, through their online service but she has been also looking in flea markets for every possible document related to her topic.

Although Au does not share her research methodology, one can suggest from the construction of her work and from the documents she displays along with the film that she follows various threads according to three separate yet connected directions: time, space and symbols. In the end, all her research material forms a constellation and an original network of signifiers.

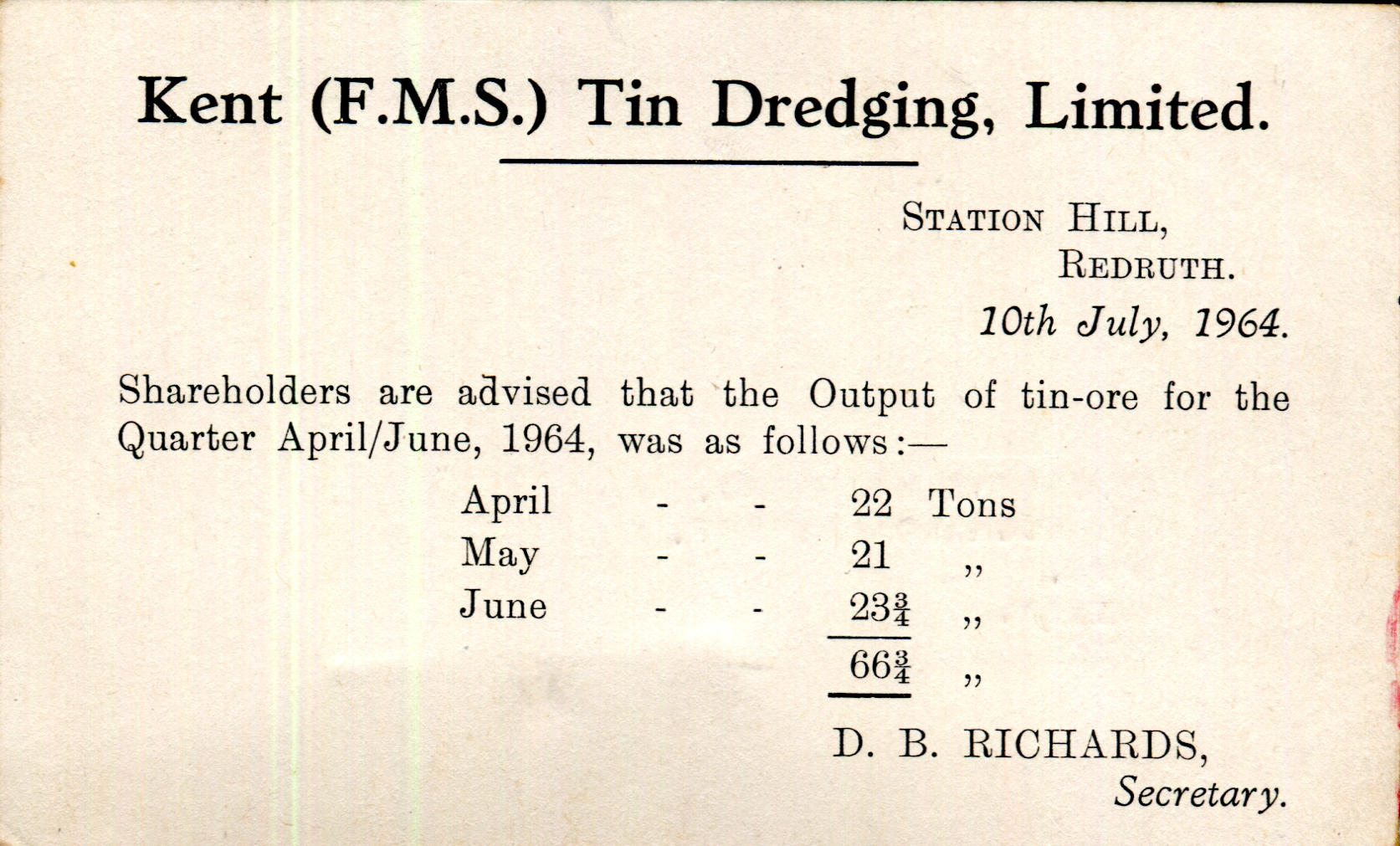

The artist’s period of focus starts with World War II and the Japanese occupation of many parts of Southeast Asia, and ends in the 1960s with the decline of the Malay film industry.[25] Au is collecting Cathay-Keris archival material and news images but also clippings and any kind of visual material and daily objects from that time such as the film company logo, archival photographs and film posters featuring actress Maria Menado (Maria is also the name chosen by the artist for the main character of The Never Ending Tale.) For the artist, 1964 represents a key date because the country was already independent yet still attached to Singapore. It was also the year of Loke’s death. In her display, she combines an official note from Kent Tin Dredging Limited indicating the British tin production for the April/June quarter of 1964 with an anonymous photograph of young boys camping in Thailand, and dated also 1964.

Image: Tin production for the April/June quarter of 1964

Archival image belonging to Ravi’s collection and displayed in the installation

Courtesy of the artist

Each element of Au’s research opens new paths and nourishes her creative process. British mining took place mostly around the region of Perak, where the artist has shot some parts of the film. From this specific place, she delved into historical and topological investigations. Bukit Larut, in the state of Perak, is a hill where the British established their residence in order to have a view on the local tin mining activities. It was renamed Maxwell Hill after the British colonial administrator George Maxwell. It is also an area known for its biodiversity and for its climate, being one of the wettest places of the country. This lush jungle was home of the Malayan Communists who were hiding around Taiping and inside a famous cave in Perak called Gua Tempurung. Some graffiti left by the guerillas can still be seen today. All these places feature in The Never Ending Tale, although with different connections. In the film, Bukit Larut is also a shaman who can sing and eventually transform into a tiger. Incidentally, George Maxwell published a local stories book in 1907. Titled In Malay Forests, its cover features a running tiger.

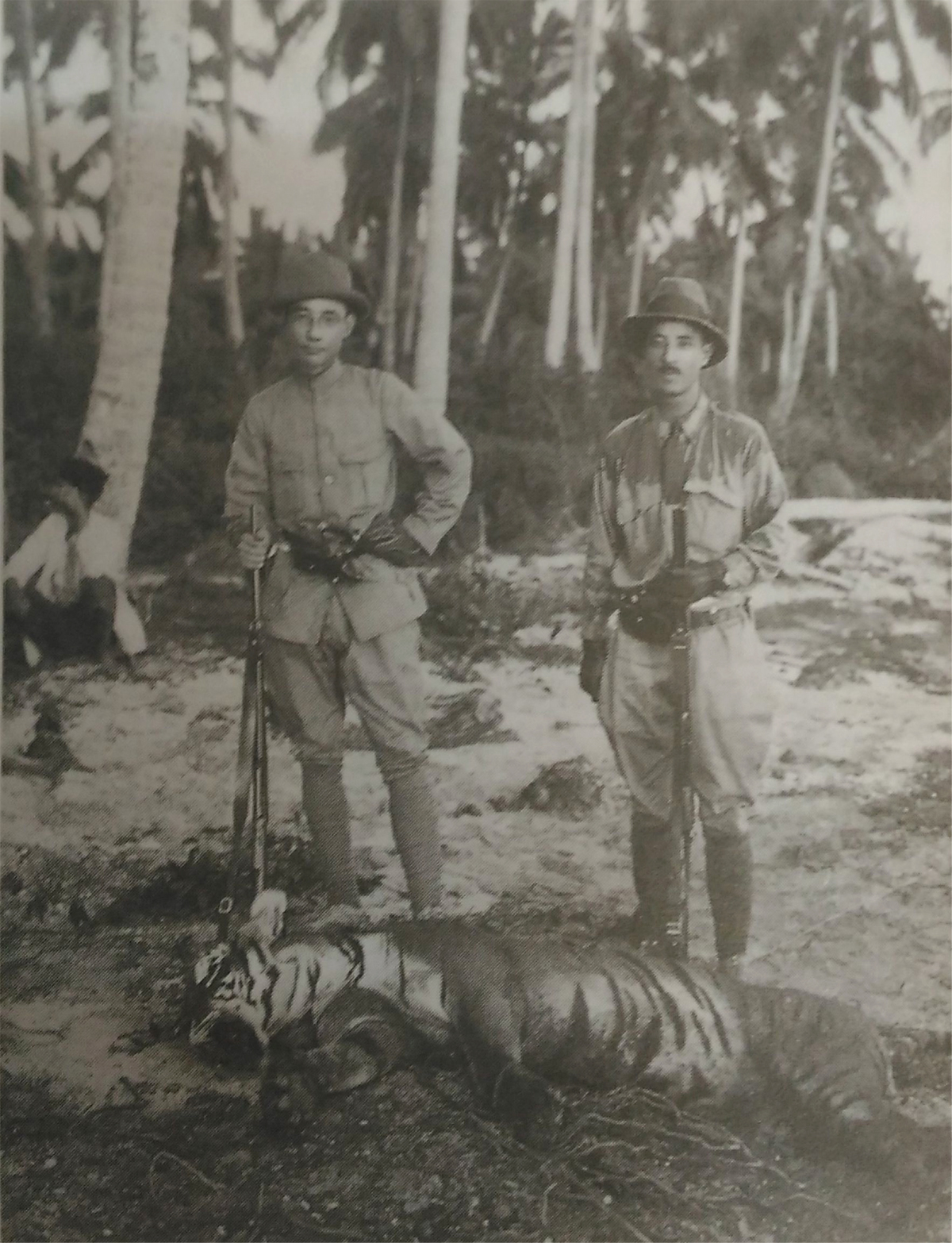

Image: cover of George Maxwell’s book In Malay Forests

Au’s research unfolds according to analogies, jumping from one field to another. The figure of the tiger is a good example of this process, with tigers - real or metaphorical - connecting different topics. Au collects everything dealing with tigers in Malay culture, from boxes of tiger balm to the Malaysian airline’s logo featuring a flying tiger, local children stories and advertisements for Tiger beer, a drink very popular in the Malay Peninsula. Its slogan “Time for a beer,” refers as well to Anthony Burgess’s novel Time for a Tiger (1956), part of his Malayan Trilogy, which takes place during the country’s decolonization process. It seems that every tiger leads to another one. At the beginning of The Never Ending Tale, Au included black and white footage from Marai no Tora (which means "The Tiger of Malaya"), a 1943 Japanese film which tells the story of a Japanese secret agent and famous bandit who operated along the coast of the Malay Peninsula. A local hero who died in 1942 in Singapore, he is remembered as “harimau,” which means tiger in Malay. To fight the Malayan Communists, the British launched the “Operation Tiger” and Templer was known as the “Tiger of Malaysia.” The tigers were also the guerilla fighters who hide in the jungle. Finally, in the region, some tigers are known for their ability to transform and the artist has also investigated this cosmological belief as a metaphor for plural identities. These ‘weretigers,’ half-human, half-animal creatures, are an important source of inspiration for many artists of the region.[26]

Image: archival photograph featuring tiger’s hunters and belonging to Ravi’s collection of documents.

Courtesy of the artist

Mythologies, folklore stories and cosmologies

In her practice, Au draws also on classical literature, pre-colonial traditions and regional folk tales. We already mentioned the two major Indian epic tales, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata from which she borrows freely some ideas, images and inspiration. In the artist’s narrative, Ravana, the demon king of Lanka from the Ramayana, is not defeated by a heroic Rama, though, and Maria/Sita is not saved by anyone: Au deconstructs these well-known tales and raises doubts about their traditional climax. Again,nd cloves). [27] In particular, the scholar emphasizes spices’ symbolic meaning or supposed values and links them to the supernatural. These ideas probably fueled an erotic image of Malay women.

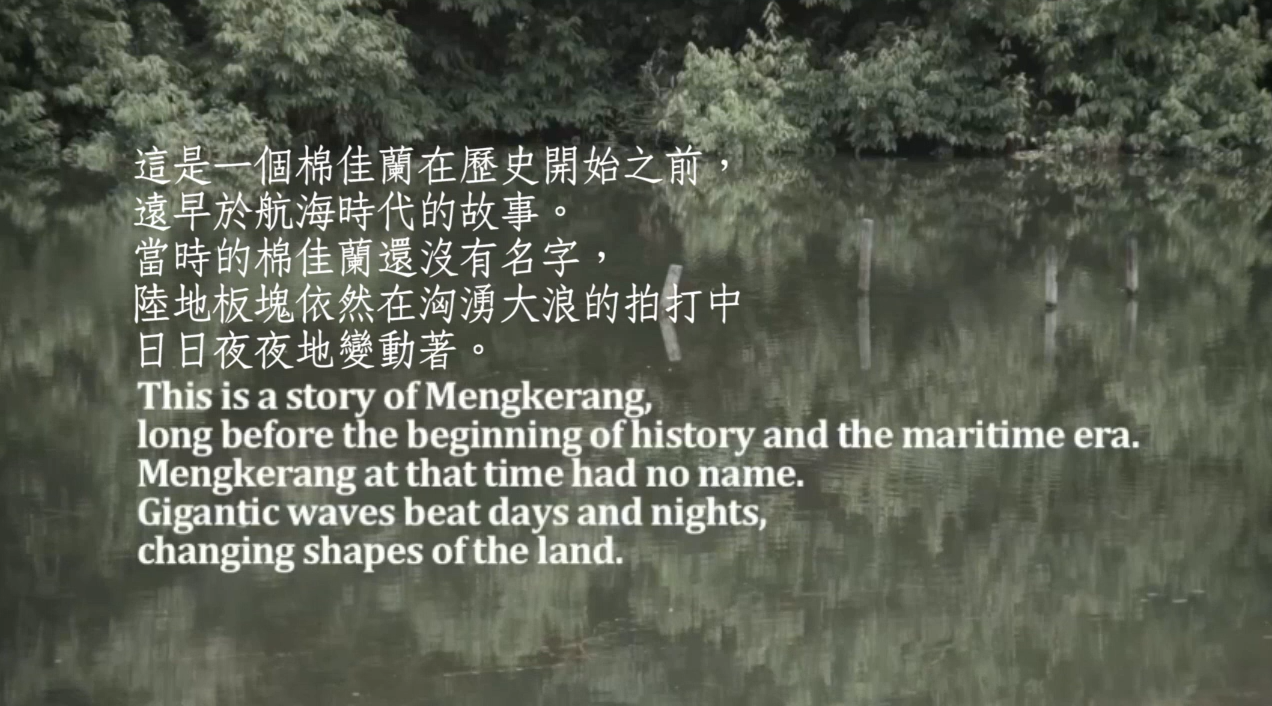

Image: Kris Project I: The Never Ending Tale of Maria, Tin Mine, Spices and the Harimau

still image from video (beginning of the story)

Au drew also on Malay tales suc her research process seems to follow specific threads that rather connect different dimensions of the Malay culture. In the Mahabharata, for instance, fragrance plays an important role: one of the main characters, and the ancestor of the heroes, was known for her irresistible body smell, which seduced the king, opening the path for drama to arise. In Au’s narrative, it is said that “a fascinating fragrance came out from Maria’s body,” and that “the story of Maria carried the smell of eternality.” In her journey, Maria meet also a bomoh, or shaman, who is said to carry “fragrance made from colorful spices.” For the artist, spices refer as well to the colonial trade, which deeply influenced the history of the region. In the exhibition, she mentioned The History of a Temptation, a book by Jack Turner which describes the commercial history of spices (pepper, ginger, cinnamon, nutmeg ah as the ones compiled by Walter Skeat in the end of the 19th century, when the English anthropologist traveled in remote places of the Malay Peninsula to collect oral stories from the villagers.[28] From this compilation, the artist was especially inspired by The Malayan Deluge which tells the story of a great flood that came down the mountains and covered all the land except some hills. After the flooding, “the sun, moon and stars were extinguished, and there was a great darkness.” When the sun returned, there was no land anymore but an immense sea. Similarly, at the beginning of The Never Ending Tale, all the habitations have been overwhelmed by a great sea after a time of great darkness. Then, “Mengkerang that yet had a name revealed itself in a sudden thunder under the layering intersections of the massive ocean.” There are many myths and cosmogonies from various traditions in which a flooding marked the beginning of a civilization. It is the power of tales to connect different cultures and epochs, and Au obviously plays with these open interpretations.

Featuring a tiger, the artist refers as well to a tale from Sri Lanka (Lanka being the kingdom of Ravana) whose title is “Mengkarung Mengalahkan Harimau Bintang”, or “The Stink Defeated the Starred Tiger.” The Malay word Mengkarung is very similar to Au’s fictional place Mengkareng. It refers to a kind of small lizard that can regenerate when its tail is cut off. Perhaps this similarity could be read as a metaphor for the resilience of pre-colonial Malay culture.

Au does not easily reveal her research sources and the work presents itself like a puzzle filled with many enigmatic riddles, puns and references that the audience can try to solve or unmask. There is no need to relate to them, though, since Au’s tale stands on its own. Besides, viewers can probably spot references that are not originally included in the film, thanks to the ambiguities of the stories, sounds and images that fuel the power of imagination and echo universal mythologies.

Artistic transformations of the research findings

A fictional framework and narrative

Image: The Never Ending Tale of Maria, Tin Mine, Spices and the Harimau still image from the video (cows). Courtesy of the artist.

The Kris Project revolves around a fictional filmmaker named Ravi who also signed the film. The objects displayed in the installation are said to be part of his collection of documents. “I believe that the presence of unfamiliar fictional characters can sometimes better reflect some problematic parts of history. The balance between fiction and reality differs from an epoch to another, but I think that conversely historiography is a political act that is very much like fiction.”[29]

The staging of the archival material and documents aptly introduces this duality: one the one hand, the evidence of the archives with their dates and references, and on the other hand their fictional belonging. Such a staging allows viewers to feel immersed in a paradoxical environment that mirrors the film’s ambiguity and diffuse a sense of awkwardness intented by the artist. At the same time, Au does not really hide this fictional framework. In the end of the film, the credits clearly mention “a film by Ravi (through Au Sow-Yee, his heteronym).” One of the cartels referring to a black and white photograph featuring a group of young men around a campfire taken in 1964 says that “That’s me, second from left,” but this example is more an exception, and Ravi does not really interfere with the work. The artist rather suggests that the fictional dimension of the work originates in reality. Ravi’s archives are also exhibited to give some clues to the viewers as to how some parts of the film could refer to real events.

Produced by a fictional film production – Kris Film Studio, the film borrows the narrative style of tales, and therefore implicitly presents itself as a fiction: “this is a story of Mengkerang.” (…) “Mengkerang at that time had no name. Gigantic waves beat days and nights, changing shapes of the land.” This beginning immediately connects the viewer with ancient mythological tales and myths about the origins, that are common in all cultures. Mengkerang does not mean anything but it sounds like a Malay name. After the flood, the story continues, a land emerged and Mengkerang arose in a sudden thunder. During these times of “great darkness,” the Sultan had a daughter, named Maria, although the narrator introduces here a doubt about her name. In fact, names in the tale are often questioned, as if the narrator, and obviously the artist, wished to prevent giving fixed definitions to any identity, which should rather be defined by their fluid state of becoming.

Maria left her father for a 14-year long exile, and her journey led her to the country of Lanka. There, she met a shaman who transformed into a tiger and, after going with Maria into a cave, eventually ate her. However, she did not die, but turned into a hybrid creature, half-human, half-tiger. It is said that her roar was so loud that it shocked the forest of Lanka and divided it into countless islands. It might be why Ravana suddenly awoke after hundreds of years of sleep. The demon and Maria fought for seven days and seven nights until Maria stabbed him in the chest. In turn, and before dying, Ravana hurt her with his dangerous teeth that could put people to sleep. From that moment, she fell asleep and could not wake up again. She started to dream and her body became both an island and a piece of the ocean while she became the new sultan of Mengkerang. The tale concludes that “probably Mengkerang was only a moving co-ordinate in the ocean of ruptures.”

Is this all but a dream? The film finishes with a fixed plan of a migrant worker, asleep nearby his pile of wood. Archival black and while images feature joyful traditional dances and one wonders if the logger is dreaming and wishes to go back in time.

It is actually almost impossible to summarize the narrative, since every sentence is open to various signifiers and functions as metaphor. Behind this fictional framework, Au questions the making of history and the continual process of historical narratives that shapes every nation and its “imagined community”[30] through the construction of a collective memory. She suggests this is a “never-ending” process, just like her tale which offers no neat end: it is said that each time the darkness arose, the story of Maria begins all over again. As with writers from the Magical Realism trend – and Au likes reading novels by Italo Calvino and Jorge Luis Borges – fiction is here at the service of reality and operates as a way to make visible its underlying layers.

Collage and ruptures

By its form, the title of the work already suggests the idea of a collage with each keyword juxtaposed in an enigmatic way. Similarly, the film itself can be seen as a collage, with various images from different sources being juxtaposed without any clear order and combined with an independent soundtrack. The narrative unfolds against the backdrop of this visual and sound composition, adding its own meaning to these entwined layers.

Image: The Never Ending Tale of Maria, Tin Mine, Spices and the Harimau still image from the video (old lady). Courtesy of the artist.

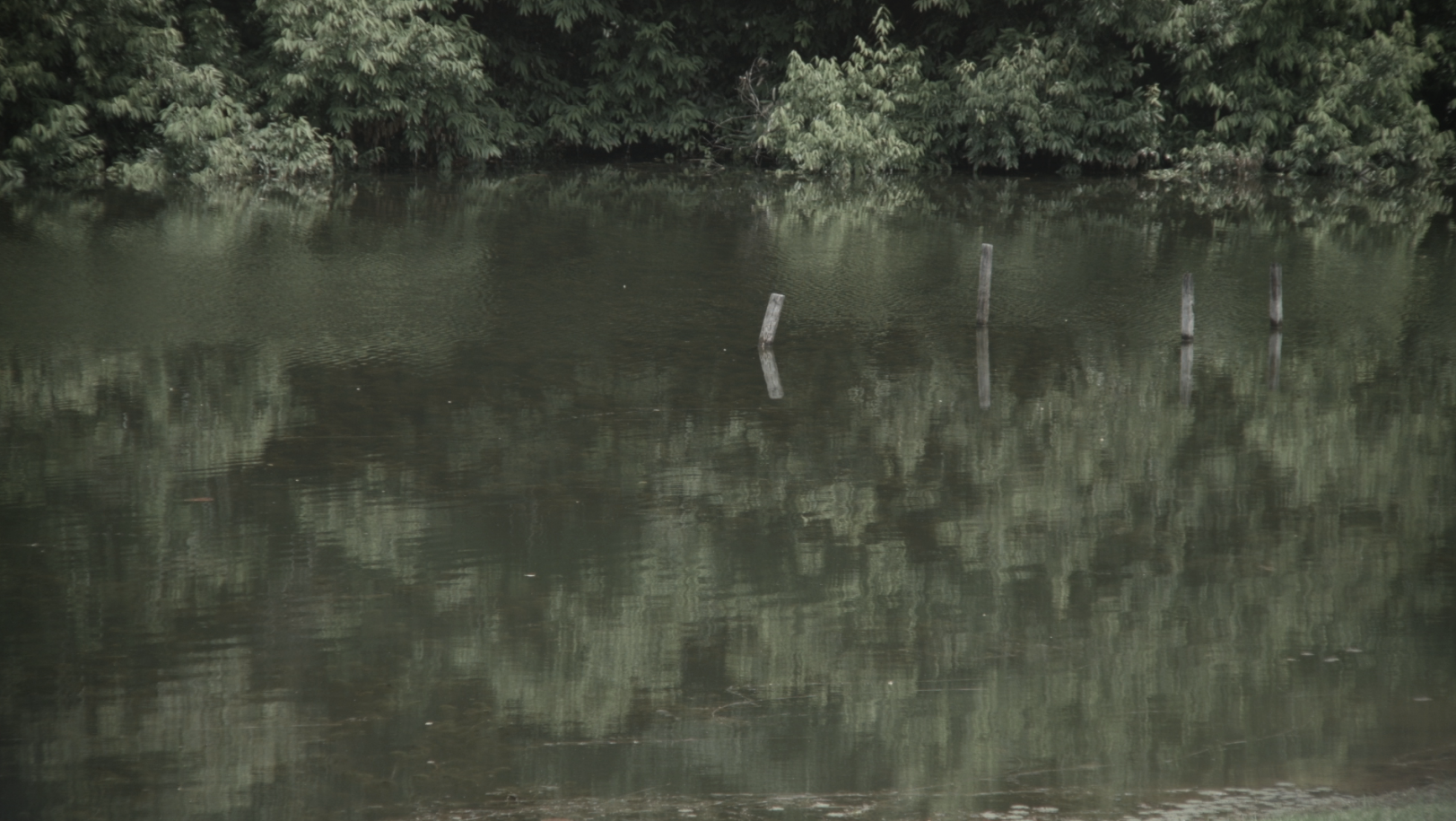

The film beginnings with a long traveling shot in the middle of a quiet and wide river, bordered by a dense jungle. Nothing moves except the camera which slides at the surface of the opaque water. It reflects the sky and trees, and looks impenetrable. The colors are very pale and greenish, as if the images originated in an old film and had faded with time. In contrast, the sound is vibrant and joyful and seems out of context: a crystalline voice singing “muchacha” transports the viewer far away from this tropical river to some Latino environment. From the start, thus, Au opens a breach in the narrative by disjointing her visual and sound material. She then introduces archival footage from films, without including their soundtrack. The music or sound creates a bridge between these decontextualized images that seem suddenly to be linked by an invisible thread. The peaceful river gives way to a black and white scene extracted from the 1943 Japanese film Marai no Tora. “Harimau,” or the “Tiger of Malaya,” is seen alone on a deserted beach while the Cuban song continues to vibrate. Finally, the singer Grace Chan appears on the screen, all dressed up in bright pinky tones, praising with her song a universal vision of a colorful world where “everywhere is home, no matter where we are, mu cha cha…” The following scene features a group of migrant workers who are probably loggers, taking a rest under a tree shade. Then, and briefly, one can see the back of an old lady seated on a wooden tilt house on the bank of a river, repairing a fishing net. Thus, in a few minutes, a typical Malay landscape, a bandit from WWII, a Chinese actress idol, migrant workers and an old Malay lady have been united by Chan’s voice and by the song’s words as subtitles.

These associations epitomize the style of the film which breaks away from any form of linearity and constantly jumps from time, places and genres in order to build its own approach of history. The artist’s research material is entirely decontextualized and used as a mere artistic material for the artist to propose a plurality of perspectives that portrays the Malay identity, and its collective memory, as complex polyphonies. For the artist, this method of editing is a way to “open up ruptures and unleash ghosts.”

In-between archival images, the artist includes her own images, shot in the region of Taiping, nearby Bukit Larut and in places where the communist guerillas used to hide during the “Malaysia Emergency.” These places are now very peaceful and, actually, the whole film unfolds in a slow pace. There are no scenes of conflicts and the violence the work refers to is only suggested by the multiplication of ruptures and by the gaps opened between the images, the sound and the narrative. At the beginning, for instance, the story mentions tumultuous times when “gigantic waves beat days and nights, changing shapes of the land.” In contrast, only birds chirping and frogs croaking can be heard within the film with, from time to time and from very far, the brief roar of an animal. The image is also very still, showing again the river, almost immobile. The artist creates here an element of tension, and one expects something might jump out of the river. However, violence remains muffled, stories remain hidden.

Image: The Never Ending Tale of Maria, Tin Mine, Spices and the Harimau still image from the video (the river). Courtesy of the artist.

Regularly, during the film, long shots of ruminating cows punctuate the story, allowing viewers to make a pause and, perhaps, inviting them to take a critical distance from the images they are watching. Some of these interludes could be perceived as ironic: after black and white footage featuring Templer visiting shops in the Malay Peninsula during colonial times, and pointing his finger at a local man as if he was visiting a zoo, a beautiful cow stares at the camera, returning us her incredulous glance.

For the music, Au collaborated with composer Sandra Tavali. The artist would send her some parts of the film and the composer, in return, would propose some fragments of music, as a basis for discussion. Besides original compositions, there are also particular references hidden in the soundtrack. Obviously the first song The World as One Family strikes for its provocative title against the backdrop of racial tensions of Malaysia, but at the end of the film, Au also includes Rasa saying, a popular Malay folk song which means "full of love," and which, in fact, originated in Indonesia. Since both countries claim it as their national treasure, it epitomizes the frictions between the countries. In 1959, a comedy film in Malay language entitled Rasa Sayang Eh was also produced by Cathay Keris in Singapore. The song appeared as well in the Japanese film Marai no Tora, contributing to the constellation of meanings and networks analyzed above. The film thus opens and closes with joyful lyrics which bring forward a form of lightness to the whole project, despite its serious topic.

With her practice of collage, the artist approaches the role of the curator who assembles particular chosen pieces in order to propose a consistent discourse that would link all these pieces together. Modelled on a fictional tale, Au’s discourse remains nevertheless totally open and unfolds in a poetic mode that recalls the Malay pantun, a traditional oral form of poetry based on metaphors.

A general process of deconstructions and mutations

Image: The Never Ending Tale of Maria, Tin Mine, Spices and the Harimau still image from the video (monkeys in the cave). Courtesy of the artist.

Whilst being embedded in the Ramayana, the story of Maria departs radically from it. The most drastic element of this deconstruction is the absence of the hero himself, Rama, who is supposed to represent the moral virtues of men, and who is the pillar of the epic in the Hindu tradition. In The Never Ending Tale, Maria (who could be seen as the equivalent of Sita, the wife of Rama) is not kidnapped by Ravana and saved by her lover. She is the heroin of the tale, and, this time, she seems to take a more active part in the progression of her destiny. Perhaps, here, the artist wishes to offer a feminist version of the tale, with Maria killing by herself the unrivaled demon. In any case, she gives voice to a usually submissive character. This might be a way to break away from the moral dimension of the Ramayana, in order to escape from any political instrumentalization of this masculine and conservative eulogy of order and established norms. In fact, the desynchronization and ruptures described in the preceding paragraph lead systematically to a deconstruction of all the featured narratives, be they built by the British propaganda, by the film industry, the tradition or by any dominant power.

Against any defined mode of thinking, Au favors the porosity and fluidity of mutations and metamorphosis. The figure of Maria itself keeps transforming, from a Sultan’s daughter to a weretiger, and, finally, to the land and to the ocean. When she leaves her father and goes to the wild forest up to the country of Lanka, the voice-over narrating her adventures is also transformed and reverberates like an echo, or a ghostly voice. During her journey, she meets a shaman and spirits whose ontologies are not fixed either. The archival footage from the film Pontianak, which tells the story of a cursed woman who can be at the same time a beautiful lady, an ugly old granny and a horrifying ghost, strengthens this idea of a general interconnectedness that links the living and the dead, the animated and non-animated things and all senses. The tale features places that can sing, such as Bukit Laru, or tin mines that can shout, while people like George Maxwell can be devoured by a passion, burn into ashes and come back under the form of a song. Maria is also able to see through a song what is happening when the bomoh transforms into a tiger, at the entrance of the cave. In turn, Harimau the tiger speaks with a voice frequency that only she can understand. In the end, while Maria has melted into the golden sand of the island, she can still hear “Maxwell’s calling from deep inside Bukit Laru.” Ultimately, these mutual mutations are a key element of the film which is not merely about a multitude of juxtaposed fragmented historical events and pieces of Malaysian traditions but about their deep interactions, conflicts and interferences that have shaped altogether Malaysia’s plural culture and history and today’s country socio-economic and political drive.

Conclusion

Image: The Never Ending Tale of Maria, Tin Mine, Spices and the Harimau still image from the video (deep jungle). Courtesy of the artist.

For their great pleasure, scholars of all times have continuously discussed every part of classical epics such as the Mahabharata, arguing about every possible interpretation. There is nothing fixed in a good narrative, and Au’s visual and sound story is just like that. The more one watches The Never Ending Tale, the more one discovers new hidden hints or mysterious anecdotes that punctuate the story of Maria. Perhaps because we have learnt too much how to “read” contemporary art, and how to analyze it, this openness is sometimes confusing. It is nevertheless gratifying to remain thus in the shadow of a poetic chiaroscuro where the imagination can freely wander and wonder.

The Never Ending Tale offers a vivid and complex image of Malaysia, made from a constant flux of disparate yet interconnected cultural, historical and political elements and influences. It suggests the impossibility of defining any national identity except by embracing its plural and ever-changing components. In some remote places of the Malay Peninsula, it is said that the village story-teller was known as a “Soother-of-care.”[31] While Au defines herself as a story-teller, perhaps her tale could contribute to soothe the multiple tensions that afflict today’s society.

[1] Following, Kris Project I: The Never Ending Tale of Maria, Tin Mine, Spices and the Harimau will be refer to as The Never Ending Tale. The two other artworks from the Kris Project are Kris Project II: If the Party Goes On (2016) and The Kris Project+: Polaris, Southern Stars and the Darken Bats (2020). The Never Ending Tale was exhibited for the first time in Shanghai, China, at the Rockbund Art Museum in 2016.

[2] The party was founded in 1973 but works in continuity with its predecessor, the Alliance Party, in power since 1957. It lost its majority for the first time in 2018.

[3] Spaan Ernst, Van Naersen Ton, Kohl Gerard, “Re-imagining borders: Malay identity and Indonesian migrants in Malaysia,” Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie (Vol. 93, No. 2, 2002): 166.

[4] The question is notably asked by Timothy Barnard and Hendrik Maier in their introduction of the book Barnard P. Timothy (ed.) Contesting Malayness (Singapore: Singapore University Press, 2004), xiii. For the scholars, the “nature or essence of ‘Malayness’ remains problematic — one of the most challenging and confusing terms in the world of Southeast Asia.” As to them, Mohamad Maznah and Aljunied Syed Muhd Khairudin emphasize that “there has been, in the last two decades, a proliferation of scholarly works that seek to re-examine the construction of the Malay identity.” Maznah Mohamad and Syed Muhd Khairudin Aljunied, “Introduction,” in Melayu (Singapore: NUS Press, 2011), xi.

[5] For the whole history of the Malay World, see in particular Andaya Leonard, Leaves of the Same Tree: Trade and Ethnicity in the Straits of Melaka (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2008).

[6] More on the role of Islam within the constitution, see for example Tew Yvonne, “Malaysia's Invisible Constitution,” in The Invisible Constitution in Comparative Perspective, edited by Rosalind Dixon, Adrienne Stone (Cambridge University Press, 2018).

[7] See for example the study conducted by Emily Kui-Ling Lau about the third generation of Malaysian Indians. Wong Ngan Ling and Lau Kui Ling, “Voices of Third Generation Malaysian Indians: Malaysian or Malaysian Indian?” Sarjana Vol 31(1) (2016): 45-54.

[8] Maznah Mohamad and Syed Muhd Khairudin Aljunied (ed.), Melayu. The Politics, Poetics and Paradoxes of Malayness (Singapore: NUS Press, 2011), xii.

[9] Maznah Mohamad and Syed Muhd Khairudin Aljunied (ed.), Melayu. The Politics, Poetics and Paradoxes of Malayness (Singapore: NUS Press, 2011), xiv.

[10] The Federation of Malaya, established after the contested Malayan Union by the British, did not include Singapore. The Malay states became protectorates of the United Kingdom, while Penang and Malacca remained British colonial territories.

[11] Stockwell A.J. “Southeast Asia in War and Peace: The End of European Colonial Empires,” in The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia, ed. Nicholas Tarling, 325-386 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 354.

[12] Newsinger John, “The Running Dog War: Malaya,” in British Counterinsurgency (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015), 33-61.

[13] E-mail conversation with the artist, April 2021.

[14] See in particular Barnard P. Timothy “Decolonization and the Nation in Malay Film, 1955–1965,” South East Asia Research Vol 17(1): 2009.

[15] Pontianak and Dendam Pontianak were directed by Filipino director Ramon Estella in 1957.

[16] E-mail conversation with the artist, April 2021.

[17] Ma Jean, “The Mambo Girl,” in Sounding the Modern Woman: The Songstress in Chinese Cinema (Duke University Press, 2015), 139-184.

[18] “Au Sow Yee – Invisible is Nothing,” Cobo Social online magazine, Oct. 3 2017. https://www.cobosocial.com/dossiers/au-sow-yee-revealing-the-invisible/

[19] Van der Heide William, Malaysian Cinema, Asian Film: Border Crossings and National Culture (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2002), 22.

[20] See for example Chandra Muzaffar, “Malaysia: Islamic Resurgence and the Question of Development,” Sojourn: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia Vol 1(1) (1986): 57-75.

[21] Maznah Mohamad and Syed Muhd Khairudin Aljunied (ed.), Melayu. The Politics, Poetics and Paradoxes of Malayness (Singapore: NUS Press, 2011), xv.

[22] The government is often accused to follow an “anti-Hindu agenda.” See for instance Swarajya, “Malaysia: Rising Islamisation Is Fueling Institutionalized Hindu-Hatred” Jun 2019.

[23] Van der Heide William, Malaysian Cinema, Asian Film: Border Crossings and National Culture (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2002), 163.

[24] E-mail conversation with the artist, Apr. 6, 2021.

[25] Cathay-Keris produced its last film in 1973 but its decline began in the mid 1960s with the competition of television and the absence of a market outside Malaysia. See for example Lim Kay Tong

[26] See in particular the case studies of Ho Tzu Nyen and Timoteus Kusno Anggawan, and their bibliography references.

[27] Turner Jack, The History of a Temptation (HarperCollins, 2004).

[28] Malaysian Fables, Folk Tales & Legends collected and translated by Walter Skeat 1901 (republished in 2012 by Silverfish Books).

[29] E-mail conversation with the artist, April 2021.

[30] See Anderson, Benedict, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (London: Verso, 1983).

[31] The expression was noted by Skeat during his fieldwork. Malaysian Fables, Folk Tales & Legends collected and translated by Walter Skeat 1901 (republished in 2012 by Silverfish Books).