Friction Current, 2019. installation view at the Asian Art Biennial, Taichung.

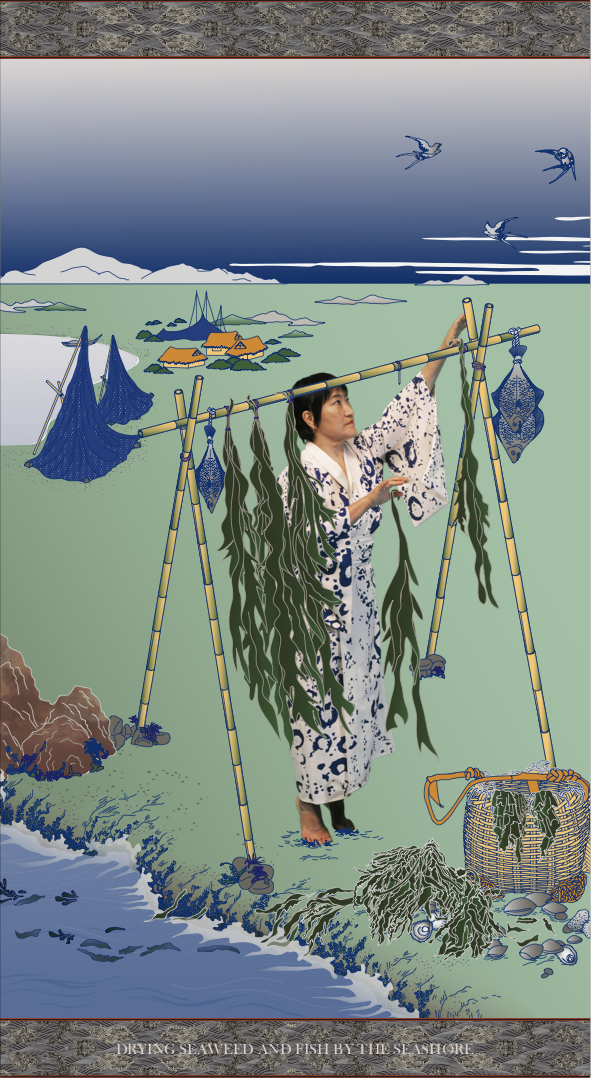

Friction Current: Magic Mountain Project is a multi-media research-based installation by Thai artists duo Jiandyin created for the 2019 Asian Art Biennial. Inspired by the Biennial’s theme of Zomia, and by the mountainous zones overarching various states of Southeast Asia, the work delves into the illegal jade and drugs trafficking that unveils a border-free network of transnational connections flourishing across the region. It aims to turn visible these fluidtrans-disciplinary relations that link the political, social, economic,cultural but also scientific and medical spheres within today’s systems of power. As such, the installation is the artistic embodiment of the artists’foray into the fields of geology, chemistry, economy, culture and politics. It mainly consists of a sculptural water fountain made from marble and jadeite, and operating with drug-contaminated urine instead of water, a single-channel documentary video depicting the carving of the jadeite piece, and various drawings and artefacts that dialogue with these two main artworks. All these elements crystalize and condense in a very original manner the complexity of the regional context and the issues at stake, inviting the audience tophysically perceive the hidden violence that sustains jade mining and meth trade.

Established in 2002, Jiandyin is an interdisciplinary collaboration between Thai artists Pornpilai Meemalai (b.1968) and Jiradej Meemalai (b.1969) who live and work in Ratchaburi, Thailand. The artists, who work also as curators, mainly explore the impact of capitalism and state authority on humans and communities. They often engage in fieldwork and community-based projects. In particular, with their series Dialogue: Seeing and Being project (2010 – 2017), they have been drawing portraits of various people from very different communities across the world, establishing with them intimate and unique relations.

Artists at work, Asian Art Biennale, Taichung 2019.

Contextual framework and artists’ drive

Friction Current: Magic Mountain Project is part of a larger and long-term project entitled The Magic Mountain, named after Thomas Mann’s 1924 novel. In particular, it derives from the artists’ research project The Ontology of Gold: Magic Mountains (2017) during which the artists engaged with 10 villagers from the Ban Khao Mo Community in central Phichit province in Thailand. Because of the local gold mining activities, the place has been strongly polluted with heavy metal and the local population is suffering from arsenic contamination.[1] The duo established contact with the community and proposed to draw the portraits of some villagers, opening a space for trust and dialogue to arise. The villagers told them stories that they usually do not share, allowing the artists to better understand the situation and the consequences of metal or minerals mining both on humans and on their environment. Observing in particular the high level of amphetamine consumed by the workers within the mines, they decided to further investigated the connection between jade mining and drug trafficking. Friction Current explores these complex interactions and the fluidity of these networks that flourish at the crossroad of legality and frontiers in Southeast Asia.

Geological and political frictions: jadeite

Jiandyin, The Alchemy[22] (2019)

C10H15N Human urine, Refrigerated cabinet 120 x 120 x 200 cm.,Jadeite Ø 12.7 cm., Marble sphere water fountain Ø 60 cm. x 50 cm., Immersion Sturgeon waterproof contact microphone, USB audio interface, Controller, 6 sound speakers, Water pump.

Myanmar jadeite, located in north Myanmar and in particular in the Hpakant area, is famous for its high and unique quality in gemology. Also called the imperial jade, it differs from the more common nephrite gemstones and is the rarer and the most valuable type of jade.[2]It probably formed during the Precambrian and Cenozoic geologic eras when important uplifts of the earthand collisions between the Indian and Eurasian tectonic plaques formed the mountainous regions of today’s Southeast Asian peninsula.[3]Jadeite emerged from these extreme geological and chemical frictions, under high-pressure conditions and deep turbulence.[4]

Today, Hpakant in the Kachin State is well-known for its jade mines covering 14,000 hectares, also famous for their dangerosity: repeated landslides have recently caused the death of many jade pickers in search of a better life.[5] Most of the workers are often drug addict: on site, heroin and methamphetamine pills are cheaper than a pack of cigarettes and allow them to work without breaks. These laborers search for the precious rocks with their bare hands and sell them on the black market.

The jade mining industry is very controversial and its business is shrouded with secrecy. What some calls “the government’s big state secret” was indeed probably worth as much as US$31 billion in 2014, which amounts to 48% of Myanmar’s official GDP or “46 times government expenditure on health.”[6] Yet very few revenues reach the Burmese people. The trade is indeed “wide open to corruption and cronyism,” and dominated by the Burmese military elites, targeted by US-sanctioned drug lords and ‘crony’ companies which are companies that emerged and prospered during the military junta.[7][MOU3] The trade is deeply connected to the Burmese complex political situation and to the ethnic conflicts that date from the 1960’s, and in particular to the guerrilla that has been opposing the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) to the Myanmar army for decades.[8]While the multiple cease fires do not solve the conflicts, the state military and local ethnic armed groups have found common grounds to bargain over the jade trade. The business is also directly linked to the drug trafficking across the region, famously known as the Golden Triangle. Drug lord Wei Hsueh Kang, who also supports the United Wa State Army ethnic armed group, is for instance known for owning a group of jade companies that are arguably the most dominant in Hpakant.[9]

Despite a political and human rights-based boycott of the jewelry trade from Myanmar by the United States, and calls for changes within the Kachin State, the jade business in Myanmar continues to thrive, operating in a grey zone between what is licit and illicit, making its slippery nature difficult to apprehend.[10]

Economic, social and political frictions: the rise and prevalence of the amphetamine market

In the Golden Triangle, the production of heroin and opium has been decreasing since the end of the 1990s, compensated by a surge of the manufacturing of methamphetamine pills, much easier to produce and transport.[11] Methamphetamine (or meth), also called ice, yaba (mad drug) or ‘little pink pills’ in Thailand, were originally produced legally in Bangkok. In the early 1990s, production was banned and most of the meth factories moved to the country’s remote hills in the north, and then to the Wa area, a semi-autonomous province in Myanmar bordering China and Thailand. For the Wa state, it was a good opportunity because they needed money to pursue their guerilla with the state.[12]

Just like the jadeite trade, drug trafficking is indeed deeply connected with the political and military situation of Myanmar, with both local warlords and pro-government militias involved in drug smuggling. “Officially, Myanmar’s government has sworn to defeat this ‘drug menace.’ (…) Yet, “the government is quietly fueling the underground narcotics trade. Some of the trade’s new key players are, in fact, militias created by the army itself.”[13] According to the United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime, the meth trade is approximately worth between $30 billion and $61 billion per year in East and Southeast Asia. [14] It is difficult to enter the northernmost regions where meth is produced: controlled by ethnic armed groups, they are also covered by jungle and hills and appear as no-go zones.While heroin production can be estimated by analyzing poppy fields from satellites, “meth production is far less traceable. It is synthesized inside huts and hidden factories that look completely unremarkable from space.”[15] As such, drug trafficking escapes any attempts to grasp its functioning. What can be said for sure is that meth pills are pouring into the region across porous boundaries, and in particular into the jade mines’ camps where they turn even children into drug addicts. They are also very common in Thailand, where the artists come from, with Thai people being the first consumers of meth in Southeast Asia.[16]

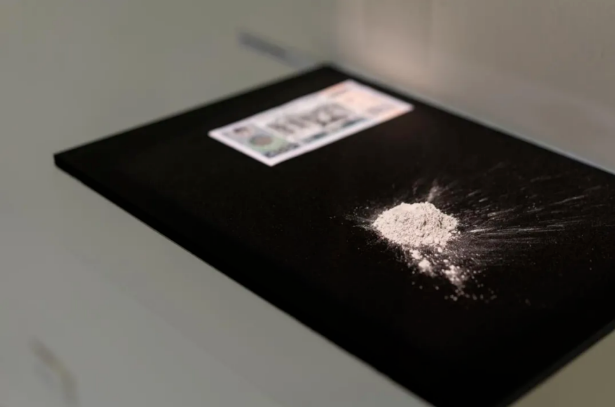

Jiandyin, Magic Mountain, 2019

Wooden shelf - Black acrylic 29.7 x 42 cm., 5g. NaAlSi2O6 Powder, courtesy of the artists.

Beyond frictions: a complex yet fluid network across Zomia

Friction Current, the installation’stitle, directly refers to James C. Scott’s famous book The Art of Not Being Governed that theorizes the concept of Zomia in the Asian uplands, defined as a zone of anarchy and refuge.[17]Their remoteness creates what Scott calls “frictions of terrain,” geographical constraints that have confronted the various lowland states with inaccessible, therefore ungovernable, territories. Its inhabitants were not primitive ancestors, as it was previously thought, but “barbarians by design,” fleeing the authority and rules of the state.[18]In fact, most ethnic groups from the Southeast Asian Massif cannot be defined by their nationality and are transnational.[19]They continuously straddle borders and redefine territories outside the national frameworks.

The jade trade between Burma and Thailand relies as well on non-state regulations.[20]Wen-Chin Chang defines it as an “underground trade,” “black market economy” or“shadow economy” taking place in a grey zone across the Burmese, Thai and Chinese frontiers. In fact, according to the researcher, about 80 per cent of Burma’s total consumer goods before 1980 originated as smuggled merchandise, mostly from Thailand, and this mode of trade prevails today. Her description of long caravans routes that used to cross boundaries remind us that national frontiers should be perceived as “interfaces” rather than fixed borders, echoing again the concept of Zomia.[21]As for the drug’s market system, it operates through cash only, beyond any state jurisdiction.

The local people from the highland have their own version of the birth of their world and cosmology. The jadeite stones are “rocks from theheaven” and a local tale says that “mountains are wrinkled lands, sewn by special thread.”[22]Drawn by this poetic description, Jiandyin investigated these invisible threads that sow these lands together. In Friction Current, they seek to reveal the deep trans-disciplinary connections that link the political, social, economic, cultural but also scientific and health spheres across the state boundaries of the region. Due to the implication of high-level members of the elite from all the countries involved, the topic tends to be taboo and is not publicly discussed, especially in a region where the freedom of expression remains limited.[23]The artists like to refer to it as a form of black magic and feel the urgent need to address it.

The artist-researcher

Connecting the dots: excavating invisible threads

Cover of the book Shan State: History and Revolution, courtesy of the artists.

Jiandyin’s research for Friction Current began in February2019, when the artists started exploring the various possible threads between geology and biology that would embody the human tragedies caused by the jadeite and drug’s trafficking. They searched for a tangible metaphor of this complex yet underground trans-national network, responsible for the death of so many. Accordingto them, in Thailand, meth is everywhere. Citizens are used to be stopped by the police in checkpoints on the highway, and be asked to proceed to a urine test. This routine experience gave them the idea to delve in biochemistry andto investigate the molecular structures of the jadeite and of the meth.

The artists work as a team and do not divide work. Their research practice involves both scholarly research and fieldwork, for they complete each other. Delving into the historical context and archives allow them to interpret and imagine things. On the other hand, in-situ research, visual perception and collection of oral histories embody their findings and trigger more emotional responses. They also write in order to support their research processes, which helps them to articulate and analyze the visual development of their work.

Among their key readings were notably the reference works of anthropologists James Scott’s The Art of Not Being Governed; Jean Michaud’s Historical Dictionary of the Peoples of the Southeast Asian Massif and Jinba Tenzin’s study of a Post-Zomian Model, which allowed them to apprehend the region from a trans-national perspective.[24] The first Western visitors’ accounts of the Burmese mines, Burma's Jade Mines - An Annotated Occidental History by American gemmologist Richard W. Hughes led them to better understand the wildness, remoteness, and the extreme terrain of the sites where jadeite was formed.[25] The artists also delved into the geopolitical situation of the region, for instance with studies about the Thai-Burmese borders or the history of the Shan State and various news’ articles about drug’s trafficking.[26] In terms of scientific research, they investigated the chemical formation of the jadeite and meth and studied their molecular structures, respectively NaAlSi2O6 and C10H15N.[27] The visual representationof their chemical components inspired them to carry further the network’s metaphor, supported by their reading of French anthropologist Bruno Latour and his enlarged vision of society as a network of multiple forces entangled in what he calls the Actor-Network Theory.[28] Finally, the artists explored the local folklore of the region and were strongly influenced by two novels, Thomas Mann’s Magic Mountain which gave its title to their Magic Mountain Project (2015- ), and Soul Mountain by Chinese author Gao Xingjian. In both cases, the narrator escapes in mountainous regions to reflect on his life, decay and illness on the backdrop of a deep crisis, World War II for Mann and the consequences of the Cultural Revolution for Xingjian. The mountains, yet, keep their secrets and hidden talismans. Their image stimulated the artists’ imagination and conceptualization of a black magic that would dominate the region.

Investigative journalistic fieldwork

Jiandyin, Urine sample bottles.

The duo did not visit any jade mine in Myanmar, and their fieldwork took a more original path. While they used to meet local people and engage relationships with them around their portraits’ drawings, they did not meet any jade picker and the installation does not feature any human being, even though their presence can be felt behind every piece.

The human dimension of the situation remains essential for the artists, yet they wished to respect the privacy of the people involved.Therefore, they decided to use meth-contaminated urine instead, as a strong symbol of the ubiquitous drug addiction and of the interconnectedness between the jade and drug trades. Besides, in order to understand how the jade market operates, they embarked on a journey to buy one stone from Hpakant in the Kachin State. Their research process resembles here the methodology of work of investigative journalists who follow secretly specific persons or goods, and reveal their illegal networks. They documented alike every step of their investigations, although did not display much of it, for they are politically too sensitive. Unlike journalists, Jiandyin prefers transforming their research outcome into visual clues and artistic interpretations.

For the artists, the human body’s secretions, and urine inparticular, became an artistic material. Through the intermediary of friends and of the police in Bangkok, they met meth users and managed to collect 8 liters of urine samples that contained traces of more than 37 different meth sources. They worked in collaboration with a specialist from the Department of Forensic, Faculty of Science, Silpakorn University in order to learn the processes of urine testing and collection. Since their request was not conventional and raised many legal issues, they finally used the urine sample from the Narcotics Control Office of a nearby district in Ratchaburi province. As such, they already experienced the crossing of the border that separates illegal and legal activities. Yet the journey was not over as they needed to testify officially the traces of the drugs in the sample. Working with the Regional Medical Science Center, Ministry of Public Health, they received the certificate proving the presence of C10H15N in the sample, which was then shipped to Taiwan according to the legal regulations.

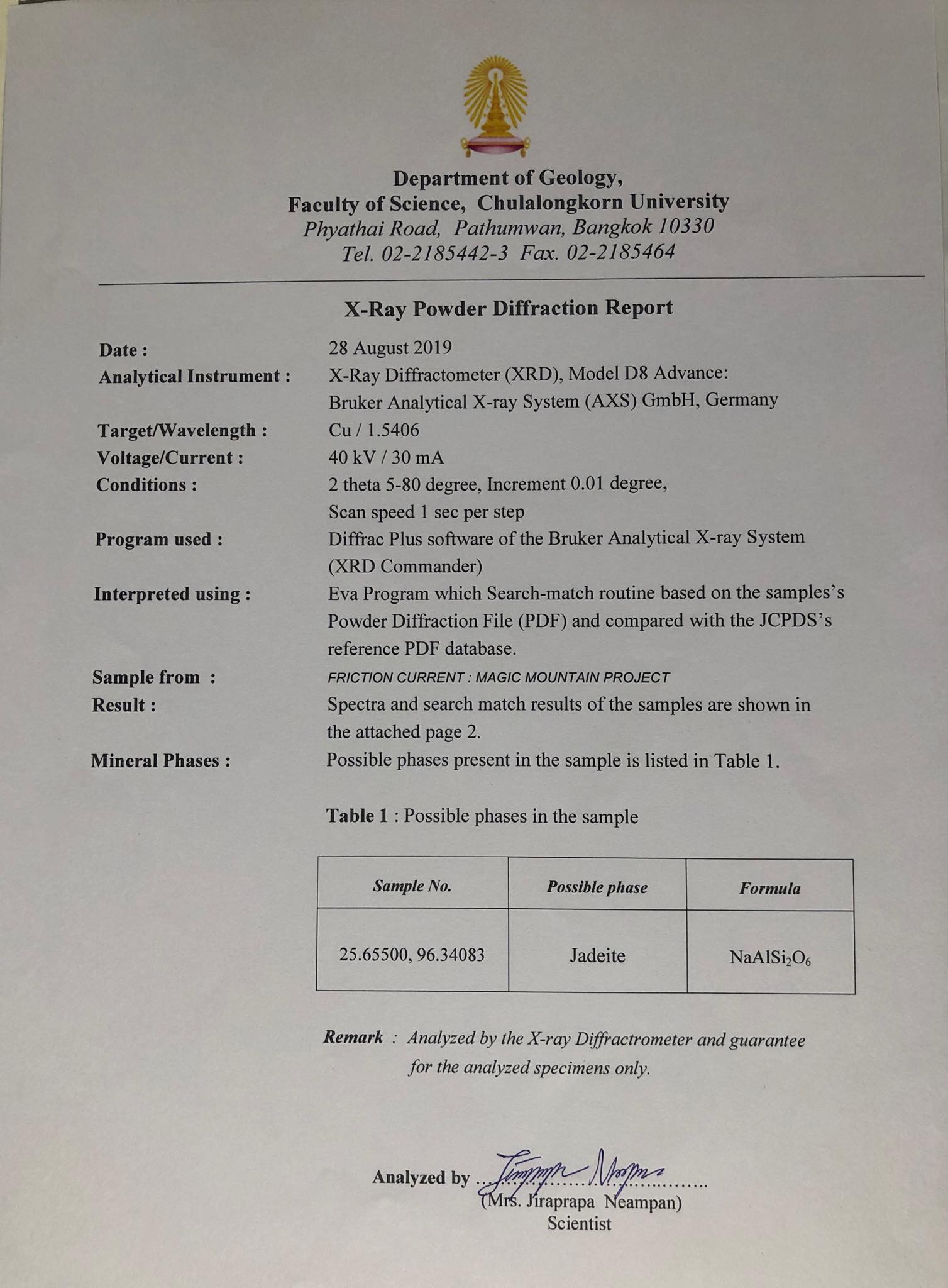

Jiandyin, Jade certificate.

In parallel, the duo searched for a piece of jadeite from the mines of Hpakant, using the underground network of this black market. They first contacted a Taiwanese-Burmese gem merchant who had been living in Thailand for 20 years and whom they trusted. He works at the Bangkok Jewelry Trade Center and can reach local stone sellers who are familiar with jadeite. He introduced them to a small shop selling jadeite rocks from Hpakant behind the door, at MaeSod District in Tak Province at the border of Thailand with Myanmar. They went through the network of middlemen or black merchants in Mandalay, which is the biggest jade market in Myanmar. To make sure that they bought real jadeite and not nephrite jade, which is much more common, they tested some samples from their stone at the laboratory of the Department of Geology, Faculty of Science,Chulalongkorn University, and obtained a certificate of the mineral components of their pieces. At the same time, they collaborated with a geologist who helped them to better understand the jadeite molecular structure.

These various research experiences, both intellectual and empirical, allow Jiandyin to physically apprehend what could be at stake behind the jade and meth trafficking. All combined, they alimented the artists’ imagination and conceptualization of their multimedia installation.

Artistic transformations of the research findings

Jiandyin, The Alchemy (2019): fountain draft for the Asian Art Biennale.

Metaphorical translations

In chemistry, a covalent bond is what provides atoms some stability through the sharing of electrons. Inspired by the biological composition of jadeite (NaAlSi2O6) and meth (C10H15N), the artists searched the covalent bond that would link the two molecular structures, in other words, they searched for a chemical relationship that could bind them together, in the same way that atoms are bound together when they share electrons. Metaphorically, this bond would bring some stability to the system, just like the jade and drug’strafficking complete each other in the process of money laundering. Since they wished to work from raw material and human secretions, the duo came up with the idea of a fountain where the contaminated urine would never dry. On the contrary, it would replace water as the basic dynamic of the water flow: just like meth stimulates the central nervous system, the urine activates the movement of a grand jadeite sphere, located on the top of the marble basin. In order to preserve the stability of the system, the artists placed the fountain into a glass refrigerated cabinet so that the temperature could be maintained.

At a glance, the audience can thus perceive the great fluidity that accompanies jadeite and meth traffics in, from and across Zomia when all relevant authorities turn a blind eye. In this fountain, entitled The Alchemy (2019), the massive jadeite ball rolls on itself, mobile, almost light, glossy and well-polished under the action of the current flow of the contaminated urine. The lubricated interplay between the liquid and the solid elements suggests the liquidity of the boundaries which separate the legal and illegal areas but also the spheres of business, bureaucracy and politics. There is no trace of workers, no human disruption except the intervention of the museum staff who injects weekly more contaminated urine in the fountain: after a few days, the meth tends indeed to evaporate. This repeated gesture illustrates the continuous need for labour exploitation that supports the whole system, but which remain invisible.

Jiandyin, The Assembly,2019[MOU4]

Paint 29.7 x 42 cm

Also metaphorical are the two images hung behind the fountain and titled The Assemblage (2019): one is an archival photograph featuring a cosmonaut in the space, and the other is an A3 illustration of the C10H15N and NaAISi2O6 molecules’ compounds. Perhaps the cosmonaut stands for the artists who tried to approach the complex topic of the jade and drug trafficking, which remain out of reach, just like the northernparts of Myanmar where the trafficking is taking place. Further than Zomia,these activities operate indeed outside any known territories, in grey areas that could be compared to space. To this inaccessible reality, the artists oppose the known chemical reality, and the perfect imbrication of the molecular elements of jadeite and meth. Their drawing, in the hues of blue, resembles an abstract composition where all the geometrical elements interlock perfectly well, reflecting again the good functioning of the chain of money laundering. Jiandyin already used this mode of representation in their animation film Khao Mo Sanatorium from their series The Ontology of Gold: Magic Mountains (2017), featuring moving 3D geometrical patterns that embodied the structure of a cyanide molecule. The work was projected in an abandoned temple of the village nearby the gold mines that caused the cyanide poisoning. Hence, on the one hand, the infinitely large, and on the other hand the infinitely small, juxtaposed as if there was nothing in-between. Again, this metaphorical representation denies the role and presence of human beings, as if they could be erased.

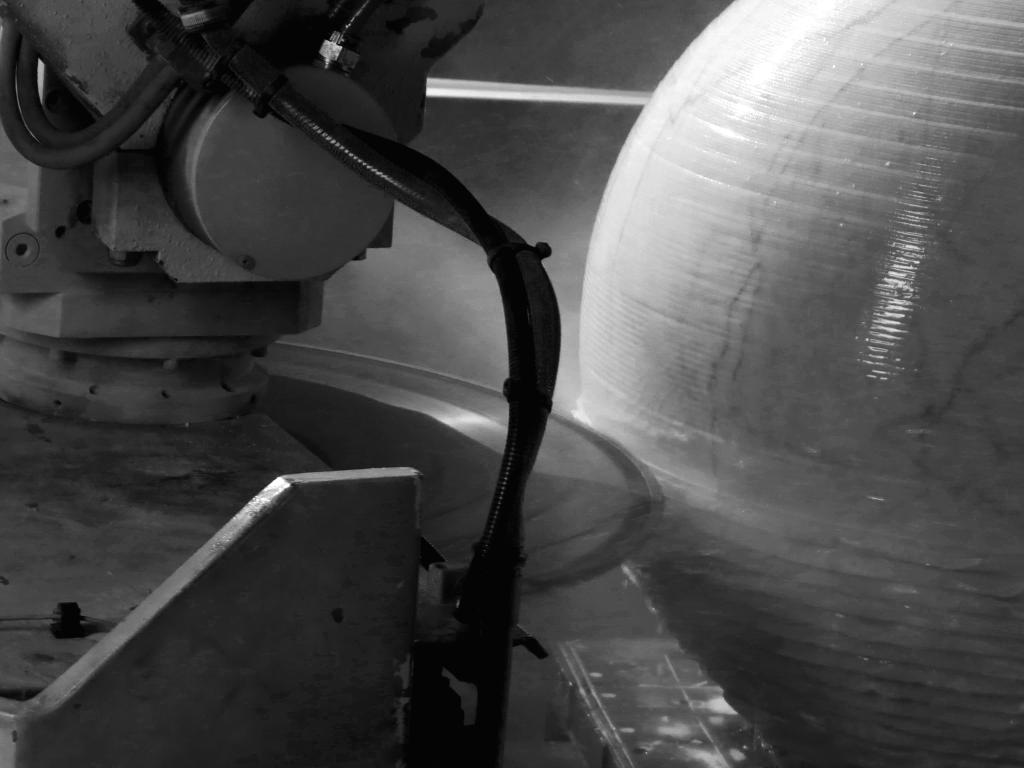

Jiandyin, Friction Current, 2019

Single-channel, Video full HD, Black and white, Silent, 20 min. 09sec, Loop

In the corner of the space, a 49-inch monitor plays a 20-minute black and white and silent video. It documents the cutting and shaping of a marble ball which stands for the jade ball from the fountain. The images focus on the polishing of the stone, and on the machine process of work that took about 72 hours. The piece of marble, carved geometrically in multi facets, stands in the middle of an almost empty factory workshop. Everything is still to the exception of a giant and circular blade that is slowly getting closer to the stone. Since the machine needs to be constantly humidified, some water drips from the blade. As it approaches the surface of the stone, it resembles a beast that would salivate in front of its prey. The camera is following its movements and close-ups bring the viewer as close as possible to the points of impact. The friction is violent. Each incision is filmed like an aggression, yet the process moves on, automatically. In fact, the machine is very precise and the violence is perfectly under control. The black and white images are highly aesthetic and the cinematographic language used by the artists resembles black and white suspense movies. Shadow’s effects and slow-motions strengthen the tension and dramaturgy of the scene. There is a strong contrast between the violence of the process, as it is metaphorically represented with the marble stone, and its final result, which is the perfect and beautiful ball of jadeite. Similarly, one could imagine the contrast that separates the fineness of a jadeite piece of jewelry displayed in a luxury vitrine, and the labor it took to extract it.

Jiandyin, Friction Current, 2019

Single-channel, Video full HD, Black and white, Silent, 20 min. 09sec, Loop

Therefore, every elements of Friction Current can unfold into many layers of meaning. A small glass vitrine contains a Chinese banknote dated from 1990, the date when China started to expand its power over the region. One side of the banknote features a mountainous landscape from the Yunnan Province, which refers here to the region of Zomia.The artist juxtaposed the banknote with some jadeite powder, originating in the cutting of the stone. It obviously resembles crystal meth powder, which is the purest form of methamphetamine. For the artists, it suggests the influence of China and its role in jade mining. Jiandyin stamped the back of the banknote with Chinese letters in black ink quoting the phrase of the folklore tale: “mountains are wrinkled lands, sewn by special thread.”

Curating a science-fiction laboratory space

Installing the microphone, Asian ArtBiennale, Taichung 2019.

Friction Current occupies a whole space, curated by the duo like a laboratory. Besides the fountain, which stands in themiddle and strikes by its original and voluminous presence, the audience is immediately attracted by a noise that pervades the room. It is in fact the amplificated sound made by the vibrations of the pump that operates the flow of the urine in the fountain. The artists have indeed inserted waterproof microphones that record and relay every pulsation that take place inside the refrigerated cabinet, whether the urine overflows, drops or touches the surface of the basin. The rhythm of the sound is nevertheless controlled by the artists who have defined a time-lapse of 3 minutes for the sound to go from a soft to a heavy tempo.The loop allows for a moment of silence to happen in-between. During that moment, the space is absolutely silenced since the video is also mute.

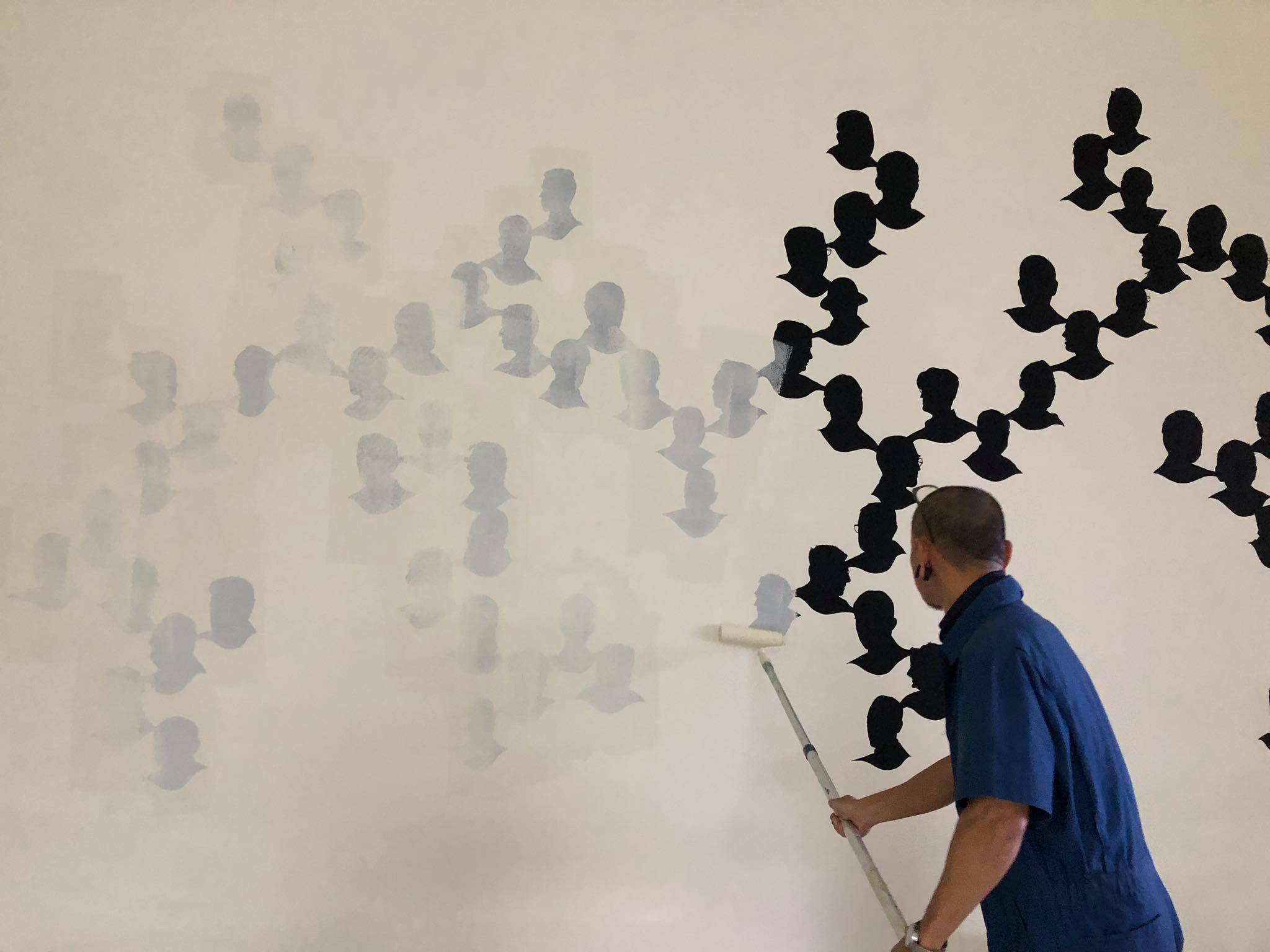

This atmosphere conveys a strange feeling. Nearby the drawings mentioned above, two original certificates document the authentication of the jadeitestone and the presence of meth in the urine sample, which fit well in a factory or a in laboratory space. However, there is no trace of human beings in such a laboratory. Except for the weekly intervention of the museum staff, the devices seem to operate by themselves: the continuous flow of the urine on the one hand, the blade from the video on the other hand. The chosen materials are also cold and dehumanized, from the marble to the empty factory workshop where the stone has been cut. A lot of empty space has been kept between the artworks and it seems that this strange factory is run by ghosts. In fact, after some consideration, the viewer realizes that the opposite wall of the entrance is not totally white and that some blurry silhouettes become apparent. They are the black faces’ silhouettes of all the people the artists found connected to the jade and meth trafficking during their research process: politicians, economists, geologists, chemists, drug lords, money launderers, chief of military, merchants, jade mine traders etc. from many different nationalities.The artists first draw their face on the wall in black, just like shadowcut-outs, then added various layers of white paint so that they only appear in a very opaque way. Their faces rather float on the wall, pale yet tenacious presence of all of those who are behind the complex networks of Zomia’strafficking. It is difficult to recognize them, and this is the intent of the artists who do not wish to single out any of them. Besides, the issue is too sensitive for pointing to any specific responsibility. Some viewers might infact not even see that there is an artwork on this wall, or might chose to ignore it, just like people can deliberately ignore the situation in this area and the people involved. What nevertheless dominates is the impression that a team of invisible persons is operating the system behind a veil, and that it works well. From time to time, though, the disturbing noise of the fountain recalls that it is not all smooth and stable.

The artist covering the silhouettes with white paint, Asian Art Biennale, Taichung 2019.

Hence, the staging of all the elements that creates the atmosphere of an abandoned factory, or an absurd laboratory, allows the artists to tell the viewer a story, although incomplete and hinted. It is a journey of space exploration involving chemistry, scientific techniques and biology, although it does not lead to space per se. The science-fictional part derives from the opacity of the objects displayed that seem at first useless, or incomprehensible, and are deprived of humanity. We enter another dimension, where all of them have in fact hidden meanings, and where the usual rules of society do not apply.

A personal perspective: wiping out the human beings

Jiandyin are not the first artists dealing with the entanglement between jade and drug trade in the region, yet their chosen perspective is very personal. Journalists emphasize the precarity of those jade pickers who are often drug addict, a precarity which contrasts with the high value of jade and with the money involved in the meth market. Similarly, Man Ra analyses the process of ‘precariatization’ at stake in the two documentary films Jade Miners (Wayushi deren, 2015) and City of Jade (Feicui zhicheng, 2016) by Midi Z.[29]The Chinese-Burmese filmmaker follows his brother who works in the Hpakant mine,and, while drawing a family portrait, delves into the laborers’ daily life. In his series The Price of Jade (2015), Burmese photographer Minzayar Oofocuses as well on the conditions of the workers in Hpakant, emphasizing their fragility and vulnerability. The jade pickers are seen like millions of ants searching the mountain, exposed to every possible risk, moved by their hope to become rich and stimulated by the drug’s effects.[30]

Minzayar Oo, Small-scale jade miners search a huge pile of rubble being dumped by mining companies as they scavenge for raw jade stones among the waste, Hpakant, Kachin State, Myanmar, April 25, 2015. © Minzayar Oo

Unlike these works, Jiandyin focuses on the stability and implacability of the system that instrumentalizes and crushes these laborers to the point that they cannot be represented. In the installation, only material things seem to have agency: it is not a human being who makes the fountain runs, but his/her urine. It is not a human being who operates the blade, but an invisible hand which reminds us of the capitalism’s invisible hand. Molecules, dust of jadeite, bank note or marble… this cold and disembodied universe has erased human beings and seems to have found its own independent pace, out of reach. At the same time, the absence of human beings is blatant and the relative emptiness of the room conveys a feeling of lack. The installation also questions the responsibility of the individuals and the group behind such a well-established mechanism. Only the shadow of the people’s faces can be discerned and, from afar, they almost look all the same. Their presence is thus above all collective as if their individual responsibility could vanish behind the system they created, drowning their blame worthiness in the group.

Friction Current refers to a longtime-line, from the geological times when jadeite was formed until today’s hiddentrafficking of the stone orchestrated by the drug market. Implicitly, it givesa sense of fate to the work, as if the current trade was part of a naturaldevelopment of the region. What could be conceived as cynicism on the behalf ofthe artists is nevertheless compensated by the exhibition’s time, which is muchshorter, and during which Jiandyin introduced a real-time interaction betweenjadeite and meth. In the fountain, insidiously, theacidity of the urine attacks indeed the stone and, in a long-term process, iscorroding it. Hence, with time, both the urine and the stone mutuallytransform. What if the precious jade loose its purity? Would it break down and,with it, the whole system?

Conclusion

Working like investigative journalists, the artists have accumulated knowledge about jade mining and drug trafficking across the region called Zomia, from scholarly research and fieldwork. They wrote about their research findings but did not display this discursive part of their work. On the contrary,and based on their own interpretation, they focus on the symbolic and metaphoric translation of these findings into a visual and sound artform able to crystalize the issues at stake. Because it attracted the attention of the mediafrom 2015 onwards, the topic of jade mining and drug trafficking is already known by the general public, although probably superficially. Hence, the installation does not produce any new knowledge per se but allows the audience to embrace in one glance the complexity and opacity of the topic. As such, it generates another form of knowledge, based on the physical encounter with the artworks and on the viewers’ personal feelings, thoughts and on the intuitionsit triggers. Unlike many research-based artists, Jiandyin did not contextualize the installation and, except for the two certificates, they did not display any documentation about their research process. The cutting of the jadeite stone, even though it documents the shaping of the jadeite ball, remains purposely mysterious and there is no voice-over that could comment it. The viewers are thus left alone in front of these eclectic elements and multi layers of meaning. They need to fill the gaps with their own investigation and active participation. While the artists acknowledge that the subtext included in the installation could be simplified, they are not worried about generating confusion among the audience. Since the topic they address is complex, they feel that this confusion is inherent to this complexity. Moreover, they introduced some clues for the viewer to build back the jigsaw puzzle they propose. The small size of the video and of the drawings makes it difficult for the viewer to totally immerge in the work, yet the powerful image of the fountain, and its disturbing noise, are strong enough to feel and project into the hidden network that rules over Zomia and its shadow economy.

[1]Since 2015, the closure of the gold mineshas been under discussion for health and environmental reasons. See for instance https://www.reuters.com/article/us-thailand-australia-mine-idUSKCN0Y11KU

[2]Although a few other countries produce jadeite, 98% of the production comes from Myanmar.

[3]More on the genesis of Myanmar jadeite see for example Qiu ZhiLi and al., “Age and genesis of the Myanmar jadeite:Constraints from U-Pb ages and Hf isotopes of zircon inclusions,” Chinese Science Bulletin, vol. 54 no4, (Feb. 2009): 658-668.

[4]The phenomenon is known as the orogenesis process in geological language.

[5]More than 350 people have been killed since 2015 and the mine was supposed to close in June 2020. See Muller Nicholas, “A Deadly Gamble: Myanmar’s Jade Industry,” The Diplomat, July 13, 2020.https://thediplomat.com/2020/07/a-deadly-gamble-myanmars-jade-industry/

[6] Global Witness, “Jade: Myanmar Big State Secret,” (Oct. 2015):5.

[7] Global Witness, “Jade: Myanmar Big State Secret,” (Oct. 2015):10-12. Myanmar, formerly known as Burma, has been ruled by the military or junta since General Ne Win’s coup in 1962. Despite the 2015 free elections and the victory of the NLD (National League for Democracy), the militaries are still occupying most of the positions in the government. See for instance Baranay Zoltan, “Exits from Military Rule: lessons for Burma,” Journal of Democracy, Baltimore Vol. 26(2), (Apr 2015): 98.

[8]More on Myanmar’s recent history and current state see in particular Simpson Adam, Farrelly Nicholas, & Holliday Ian (eds), Routledge Handbook of Contemporary Myanmar, 2017.

[9] Global Witness, “Jade: Myanmar Big StateSecret,” (Oct. 2015):12.

[10]Chang Wen-Chin, “The everyday politics of the underground trade in Burma by the Yunnanese Chinese since the Burmese socialist Era,” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 44(2), June 2013: 298.

[11]Chin Ko-lin. The Golden Triangle: Inside Southeast Asia's Drug Trade. Cornell University Press, 2010, 9.

[12]Chin Ko-lin. The Golden Triangle: InsideSoutheast Asia's Drug Trade. Cornell University Press, 2010, 127-128.

[13]Winn Patrick, “Myanmar’s state-backed militias are flooding Asia with meth” Global Post Investigations (Nov12, 2015). Available online:

[14]Figures from 2019, quoted in Berlinger Joshua, “Asia's meth trade is worth an estimated $61B as region becomes' playground' for drug gangs,” cnn edition online (July 18, 2019). Available at https://edition.cnn.com/2019/07/18/asia/asia-methamphetamine-intl-hnk/index.html

[15]Winn, 2015 Ibid.

[16]Cohen Anjalee, “Crazy for Ya Ba: Methamphetamine use among northern Thai youth,” International Journal of Drug Policy, Vol 25, issue 4, July 2014: 776-782.

[17]The region of Zomia, originally invented by Dutch social scientist Willem van Schendel, includes five Southeast Asiancountries (Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Thailand and Myanmar) and four provinces of China. Its area is comparable to Europe. See Scott James C., The Art of Not Being Governed. Yale University Press, New Haven & London 2009.

[18]Scott James C., The Art of Not Being Governed. Yale University Press, New Haven & London 2009, 8.

[19] On the local population across Zomia, see in particular Michaud Jean et al., Historical Dictionary of the Peoples of the Southeast Asian Massif. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. Second edition, 2016.

[20]Chang Wen-Chin, “Guanxi and Regulation in Networks: The Yunnanese Jade Trade between Burma and Thailand, 1962–88,” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 35 (3), October 2004: 479-501.

[21]Chang Wen-Chin, “The everyday politics of the underground trade in Burma by the Yunnanese Chinese since the Burmese socialist Era,” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 44(2), June 2013: 292-314.

[22]The artists found this quote in the Yao mythology. The Yao are an ethnic minority from the Guangxi autonomous provincein southern China. They share some beliefs with the people from Zomia.

[23]See for instance the ranking established by Reporters Without Borders published online: https://rsf.org/en/ranking

[24]Tenzin Jinba, “Seeing like Borders: Convergence Zone as a Post-Zomian Model,” Current Anthropology Vol58, issue 5, Oct. 2017.

[25]The article traces back the history of jade mining in Myanmar from the early 19th century and reveals the mysteries and tragedies that have always accompanied this trade, but which have hitherto not been discussed. It is available online: https://www.lotusgemology.com/index.php/library/articles/283-burma-s-jade-mines-an-annotated-occidental-history

[26]See for instance Chachavalpongpun Pavin, A Plastic Nation: The Curse of Thainess in Thai-Burmese Relations, UPA 2005;Tun Sai Aung, History of the Shan State: From Its Origins to 1962. Silkworm Book 2008.

[27]Methamphetamine was discovered in 1887 by Romanian chemist LazărEdeleanu (1861-1941). The compound C10H15N in methamphetamine was synthesizedfrom ephedrine in 1893 by Japanese chemist Nagai Nagayoshi (1844-1929). In1919, crystal methamphetamine which is the most extreme form was synthesized by pharmacologist Akira Ogata (1887-1978). See for example Jumlongkul A. “Amphetamines: A review of forensic medicine,” Chula Med J. 60(4) July-Aug 2016: 399-412. (in Thai language).

[28]In particular, the artists were influenced by Harman Graham, Prince of Networks: Bruno Latour and Metaphysics. Re.press, 2009. Moreon the Actor-Network-Theory see Latour Bruno, “Reassembling the Social – An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory,” Oxford University Press, 2006.

[29]For an analysis of Midi Z’s films see inparticular Man Ra, “Homecoming Myanmar Midi Z’s Migration Machine and a Cinema of Precarity,” in Independent Filmmaking across Borders in Contemporary Asia,199-227. Amsterdam University Press 2019.

[30]See for instance an interview of the artist-reporter on Lens Culture: https://www.lensculture.com/articles/minzayar-oo-the-price-of-jade. The series was exhibited at Charbon art space, Hong Kong, in March 2018 as part of the exhibition Documenting Myanmar curated by the author.