|

| Khvay Samnang, Preah Kunlong (2017) Digital C-Print, 80 x 120 cm. Courtesy of the artist. |

For Preah Kunlong,Cambodian artist Khvay Samnang (b.1982) spent months in the Areng Valley in the southwest part of Cambodia, trying to understand the possible impact of the construction of a hydropower dam in the region. From there, the artist found inspiration from his encounter with the local inhabitants who mostly belong tothe Chong minority, and who shared with him their traditions and beliefs.

Based on this fieldwork, Preah Kunlong (2017) is a two-channel 18-minute film featuring choreographer and traditional dancer Rady Nget,wearing successively 11 animal masks, dancing in the midst of this part of the rainforest, known as one of Southeast Asia’s last great wilderness areas. The work also includes the sculptures of the masks, displayed on sticks around the video or separately. The video installation conveys the artist’s personal understanding of the mutual relationships which the local people entertain with nature, an understanding transformed as a powerful invitation to reconsider the way we inhabitthe world. In particular, this vision of nature stands out against the government’s development projects and, beyond, challenges the usual division nature/culture imposed by modernity.

There is no record of Khvay’s actual fieldwork except for a few photographs that the artist does not exhibit. In fact, Preah Kunlong never refers directly to the local context or even to the Chong people themselves: if it had not been explained by the artist or by the curator, there would be nothing left, in appearance, ofthe artist’s research process in the final artwork, which is totally converted, absorbed and embodied into Nget’s choreography. The knowledge produced by the work is thus above all sensuous, empirical and body based.

|

| Khvay Samnang, Preah Kunlong (2017). Monkey mask. Courtesy of the artist. |

Contextual framework and artists’ drive

|

| Waterfalls in the Areng Valley, near Chumnoab village. Courtesy of the author. |

An ecological urgency

The starting point of Khvay’sresearch was the mediatised controversy that took place in the Areng Valley about the construction of a hydropower dam, perceived as a threat for the local community and, in particular, for the Chong ethnic minority. The Areng Valley, and more largely the Cardamom Mountain, is known for its unique biodiversity and is home to 60 threatened species, including the Asian elephants, tigers, Siamesecrocodiles and pileated gibbons. In conjunction with the increased humanin tervention and climate changes, the usual and traditional animals’ paths aredeviated, and many species are endangered (the elephants, the Siamese crocodile)[1]or already extinct (tigers). The dam would have also caused the displacement of about 1,300 persons and flooded a 9,500-hectare area.[2] After many protests,the project was postponed but there are still uncertainties about its possible implementation.[3] Since he felt it was difficult to understand the situation from the media reports, Khvay decided to go there in order to see by himself what was happening.

In fact, the tensions and controversies that have arisen in the Areng Valley crystallise recurrent issues that plague the country: massive deforestation, illegal logging, indigenous protests for their rights or land grabbing. The Chong people belong to the Poar group, scattered between Thailand and Cambodia, and, more generally, to the group of highlanders’ inhabitants, who are located throughout Southeast Asia.They belong to Cambodia’s indigenous minorities, which account for approximately1.4% of the whole population.[4]Theoretically, they are all recognized as Khmer citizens, but in reality some ethnic minorities are still deprived of their rights, and in particular of the right to own land.[5]Additionally, and because of the richness of their lands, the indigenous people are constantly threatened by new project developments from private investors or from the government, and increasingly controlled by Non-Governmental Organisations (NGO) or new regulations aiming at protecting the natural environment, sometimes at the expenses of the local populations.

In Cambodia, there is nostrong policy that would help the indigenous communities to live through these deep transitions, develop education, alleviate poverty and secure their land. Globally,these populations are among the poorest of the country, powerless in front ofthe commercial and state interests.[6]All literature on the subject underscores the weakness of Cambodian institutions, their lack of transparency, corruption and the non-implementationof the policies supposed to empower the indigenous people. For example, the protected and wildlife conservation areas, created by the government in order to protect natural resources, are in fact “disappearing quickly owing to illegal encroachment, and in particular their illegal sale to domestic and foreign companies as part of economic land or forest concessions.”[7]

The context of the Areng Valley offers thus an overview of the complexity of the issues at stake and how much their perception can be biased according to the chosen sources of information. Alex Gonzalez-Davidson, the activist and founder of the environmental group Mother Nature who had been living in the Areng valley for years, was deported by the government in 2015 because of his activities against the hydropower dam project.

|

| Deforestation in the Areng Valley, Koh Kong province, Cambodia. Documentary photograph. Courtesy of the artist. |

A feeling of mistrust

Khvay constantly highlights the impossibility to believe either the press or the discourse of the government. This is why he had to go and see by himself. A general sense of mistrust pervades indeed the country. Today, and despite an “open face”presented to the outside world, most of the media in Cambodia are owned or controlled by the government or the ruling party. Sebastian Strangio, who is a journalist specialized in the region, points out that, actually, “a free and impartial press has never really existed in Cambodia.”[8] Politically,the country has been governed by the same Prime Minister since 1985, with little room for any form of opposition.[9]On the legal side, despite a liberal democratic Constitution, voted in 1993, Professor of Law Catherine Morris underscores the corruption of the law and the weakness of the legal system, observing that “corruption and lack of independence from the ruling party have corroded public trust in Cambodia’s courts, police, lawyers, and public officials.”[10]

In this context, it is easy to understand why the artists feel the need to engage in their own investigationsin order to make their own judgements. While activists are easily jailed or even assassinated,[11] and journalists often threatened,[12]the artists feel paradoxically freer, and they are the ones who address the sensitive topics. Besides, research is another way to regain agency and to actively respond to this context of authoritative power. The practice of documenting reality and working in the field is totally new in Cambodia and responds to this specific context: as Pamela N. Corey recalls, art students have been trained almost until today to remain confined in their studio since the French colonial era. “New forms of photographic practice, which involve dimmersive looking, active research and planning opened up avenues for alternative conceptual models via engagement with public space.” [13]

The artist researcher

|

| Khvay and the villagers in ChiPhat. Documentary photograph. Courtesy of the artist. |

A long journey: building trust

“Preah Kunlong was made over16 months for documenta14 during which time the artist and various collaborators spent around ten week long stays in Areng Valley and Chi Phat, inthe southwest of Cambodia. The artist was interested to experience this unique ecosystem firsthand – the area is the largest unbroken rainforest in all of Southeast Asia. He had hoped to learn from the indigenous Chong people to better understand their beliefs and livelihoods, especially at a time when governmental and corporate interests threaten all life in the valley through deforestation and damming.”[14]

Khvay’s process of work isfully emphasised in Preah Kunlong and was largely described in the presentation of this particular artwork, both by the artist during his talks, interviews or statements and by the curator when the work was exhibited at Documenta 14. Infact, at the beginning of the project, Khvay was wondering how he could addressthe problem of the dam in continuity with his previous works focusing on ecological issues. Rapidly, though, he discovered the culture of the Chong people and felt the desire to learn more from them, enlarging the scope of his research interest. He had still no precise plans and arrived in the Areng Valley with a totally openmind.

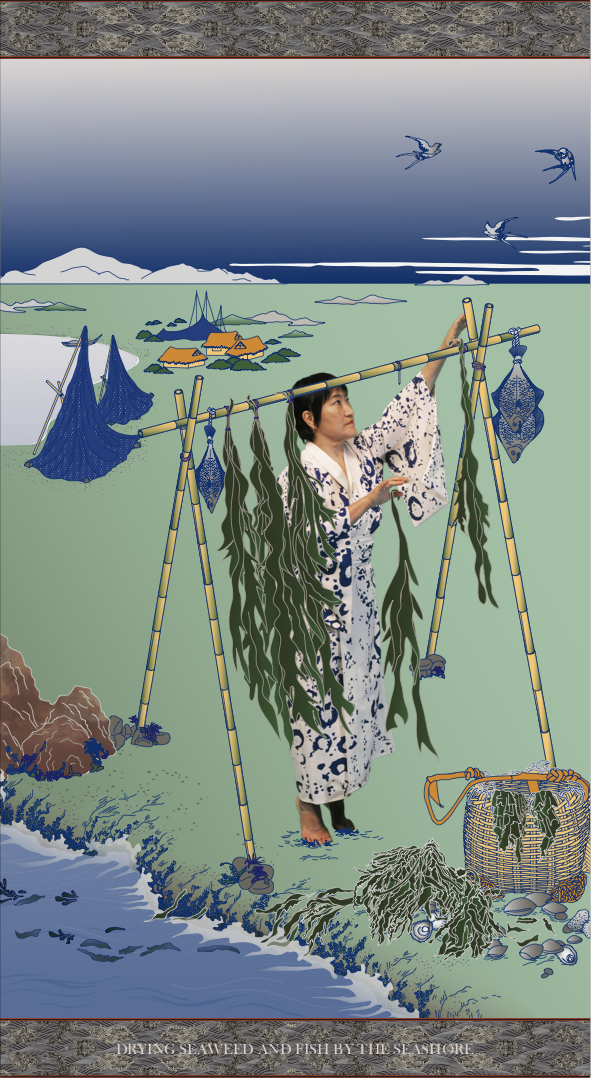

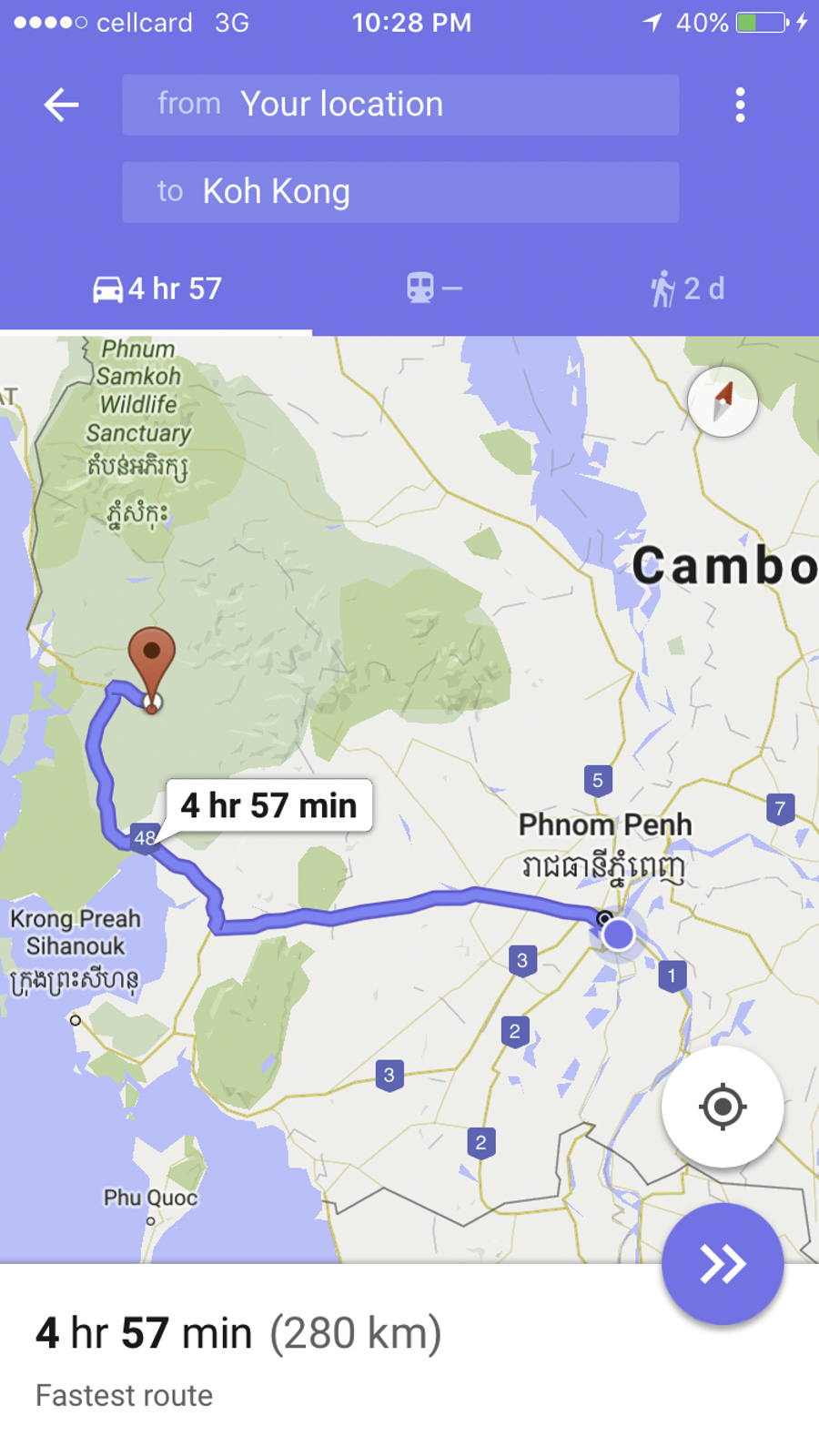

|

| The artist’s journey (map).Courtesy of the artist.

|

Going there and meeting thepeople took already a lot of time. The journey itself was an adventure since there was no road to enter the valley. Khvay established himself first in ChiPhat, a village relatively easily reachable by road, and then reached a smaller village, Chumnoab, deeply lost in the Areng valley. Today, there is a muddy road going there but at that time it was not yet built, and the village was totally isolated. Khvay and his team had to push their motorbikes through the jungle. In Chi Phat, there are Chong people living together with other communities, including Khmer people, while in Chumnoab there are only Chong population (about 100 families).[15]From Chumnoab, the artist would walk through the jungle with their local guide to reach further wild locations and higher mountains.

|

| The artist’s journey: motor bikes in the jungle. Documentary photograph. Courtesy of the artist. |

The first two visits were dedicated to initial contacts and identification of locations. Khvay tried to gain the people’s trust and to immerse himself within the community in order to understand the way they live, work and think. It actually took him a lot of time to create such a link since many locals looked at him with suspicion: the hydroelectric dam’s project had drawn attention to the area, bringing political organizations, ecological activists and journalists to the villages in addition to the Chinese investors. In this context, the indigenous people were not inclined to trust anyone as the tensions were growing. At first, he presented himself as a tourist, and later explained that he was an artist doing research in order to create an artwork. During the project, some local people chose tomove away from him, afraid that working with him would affect them negatively.In Chi Phat and Chumnoab, he seems however to have been really accepted as a member of the family and he is still invited to go back there for weddings, housewarmings or other ceremonies.

Another difficulty was the language since most of the Chong people, while they do not use anymore the Chong language, speak Khmer with a strong accent. Later, it is only by living with them that Khvay managed to learn more about their traditions and beliefs,collecting bits of them little by little. In fact, most of these traditions have already been forgotten and it was not easy to have the old people reminding them.

Khvay conducted many informal interviews with local villagers but did not record them. He only took a few photographs as a way to document his research. These photographs are not on display with the installation, though, and are kept by the artist for his personal use or as supports of his public talks. When I asked about the reasons for this absence of documentation, he told me that he could only get information about the Chong culture when he was drinking with them, and that it was difficult to record such moments. Moreover, since he was trying to establish a trustful relationship with them, he did not wish to write anything in front of them, nor to take photographs. Hean Sokhom, who focuses on indigenous people from the northeast territories, notes that they “are not likely to tell an outsider their own identity”[16]especially when they live nearby the Khmer population, because of their fear of xenophobia.

|

| A traditional kitchen in Chumnoab village. Courtesy of the author. |

Delving into local traditions and beliefs

It is indeed difficult to precisely define the Chong community and their culture from the outside.There have been actually very few scholarly works dealing with the Chong ethnic group and their kin,[17]with most of the scholarly work about the Cambodian minorities and indigenous people focusing on the Northeast region.[18]Today, the Chong people are farmers fighting for their rights. They do exist as a community but they seem to be more defined by their political and economic situation than by the specificity of their culture: what bring them together is the fact that they are deprived from the right to own the land where they have been living for centuries, and that they are powerless in face of the government projects of development and foreign investment.

|

| A neak Ta in Chumnoab village. Courtesy of the author.

|

However, Khvay discovered someold stories that triggered his interest and imagination. In particular, the Chong people tend to be animist and each family worships a different animal which could be conceived as a guardian. Yet these spirits call also for respect and for certain rules to be followed. This belief is actually very common in the Cambodian culture. Alain Forest, who studied the expression of guardian spirits in Cambodia, notes for example that, in most villages, it is believed that if someone talks in an inappropriate way, laughs too loudly or insults someone not far from a neak ta (a spirit of the land), or in the forest guarded by aspirit, he/she will be punished by this spirit.[19] At the same time, some animals are said to have helped villagers, either to find water in times of drought or to find their way when they were lost, thanks to their footprints left on the ground. The title of the work could actually be understood as The Way to the Spirit (Preahmeans god or spirit and Kunlong means path or footprint), which is also the way taken by the animals of the forest. These beliefs have consolidated along relationship between the villagers, the forest and the local animals,passed on from generation to generation. In fact, the Chong people are very much dependent from their environment and there is a solidarity that links them to the surrounding nature. It is this deep connection, experienced and felt byKhvay during his multiple stays, that partially drew the artist’s inspiration.

Working freely as an intuitive ethnographer

|

| Camping in the Areng Valley. Documentary photograph.Courtesy of the artist.

|

For the American professor of anthropology James Spradley, “the central aim of ethnography is to understand another way of life from the native point of view.”[20]Yet, while fieldwork is the main feature of ethnographic research, it is clear that Khvay borrowed very freely the tools of the ethnographer: he did not follow any specific methodology of work, he did not define his object of study nor defined clearly any specific objectives to his research. Above all, Khvay never meant to work as an ethnographer and rather defines himself as a translator, interpreting what he observes, learns and feels. There is no reason, thus, for him, to deliver any specific outcomes from his fieldwork, nor to be consistent in his interpretation of the Chong culture. To complete his knowledge of the ethnic minority, and of their environment, Khvay also mentions reading a few articles and reports such as the reports from the Mekong Wetlands Biodiversity Programme.[21] He nevertheless acknowledges that he responds better to fieldwork than to literature, his favourite sentence being “if I want to know, I should go.” The knowledge he gathered from his fieldwork is not indeed so much discursive but rather flows from his intuition and experience, translated in the work. From this perspective, his research approach would be closer to Tim Ingold’s empirical conceptions of knowledge: for the British anthropologist, “to know things you have to grow into them, and let them grow in you, so that they become a part of who you are.”[22]

Khvay is an urban citizen and the experience of the wildlife was new to him. In order to reach out this unfamiliar world, he tried to let his mind on the side, and to open all his five senses. At the beginning, for instance, he could not smell the presence of the animals in the jungle. His guide, a local villager from Chi Prat, was constantly telling him: “do you smell? The elephants took this way earlier this morning.” But he was unable to smell anything. However, after long journeys into the rain forest, he suddenly smelt it. He said it worked like a curtain that abruptly opened, revealing a world that was hitherto hidden. This is when,probably, he started thinking with his body, or when he ceased to be an outsider in the jungle: being able to see from inside.

On his side, Nget Rady, who is the dancer featuring in the video, went also on site to accustomed himself to the jungle. He wished to “feel” the spirits of the animals and the energy of the place and of the natural elements, which inhabit his dance once he wears the masks. In order to know more about the 11 animals he had to interpret, he went also to the zoo in Phnom Penh and observed them behind the bars. He spent some time observing them and mimicking their behaviour or sounds. Nget is aclassical Cambodian dancer. Since the age of 9, he has been trained to play the monkey in the Ramayana: in this traditional epoch, all the gestures are verymuch coded and precise. As such, embodying a monkey in the Areng Valley was atotally new research experience for him. Just like Khvay, he mainly followed his intuitions and learned from his fieldwork, which he did not restrict to the wildlife: in fact, his dance embodies at once the local animals’ spirits and the people and he tried to combine the feelings of both.

|

| Nget Rady at the Phnom Penhzoo. Documentary photograph. Courtesy of the artist. |

Artistic transformations of the research findings

In Khvay’s practice, one cannot clearly distinguish the artist’s research from the artistic transformation of the research findings since these processes are entangled and nourish each other. The artist learns while creating and creates while learning.

Collaborating with the villagers

|

| Masks making. Documentary photograph.Courtesy of the artist.

|

During some specific ceremonies, the Chong people may use animals’ masks, but they are very different from the ones created by Khvay. Traditionally, the people wear a hat with two horns, which does not cover the face. It is thus by discussing with the villagers and by learning their different weaving techniques that Khvay had the idea of creating the masks that featured in Preah Kunlong. An old lady proposed an original method using vines and fishing nets and they tried altogether various shapes during collaborative workshops. The mask of the peacock was the first one to be achieved successfully. Later, most of the masks were made by Khvay’s guide who also learnt how to collect vines for the artist. It took about twomonths to create the featured masks, and they all represent a specific animal-protector of local families. In the work’s caption, there is no mention of the names ofthe people who participated in the making of the masks. How to collaborate artistically with indigenous people raises several complex and ethical questions that would deserve an analysis on its own, though, and it exceeds the frame of this article.

|

| An old lady making masks. Documentary photograph. Courtesy of the artist. |

|

| Trying different shapes of the masks. Documentary photograph. Courtesy of the artist.

|

Guided by the villagers, Khvay and his team – seven persons including Nget – identified for each animal the right location where the scene could take place. Usually, the photographer working with Samnang would go ahead and check the places before they all go. For instance, for the peacock, the dance was performed in a rice field, when the rice was high. In-between those places, they often had to walk long hours, and these long hikes became part of the experience. One of the journeys lasted 10 days before they reached the waterfalls, and they often had to sleep in the jungle.

|

| Camera shooting in the ricefield. Documentary photograph. Courtesy of the artist.

|

|

| Khvay Samnang,Preah Kunlong (2017) Digital C-Print, 80 x120 cm. Courtesy of the artist. |

Improvisation

Both Khvay and Rady have assimilated in their own way what they have learned and felt during their time in the Areng valley. Combinedwith their imagination, this knowledge has driven their choices or gestures during the creation process of the work: Khvay felt where to shoot the scenes,and, later, how to edit the film; Rady felt how to move. They let their own intuitions and body knowledge drive them.

|

| Rehearsing. Documentary photograph. Courtesy of the artist. |

Khvay did not direct the choreography and did not wish Nget to perform a classical animal dance. Hesimply suggested that he would embody a half-human and half-animal creature, inhabited by spirituality. In each location, Nget would perform freely for about 3 hours and Khvay would catch the right moment when the dancer would forget who he was and became one with nature. For his part, Nget confesses he stopped being aware of any surrounding dangers once he wore the masks. He felt stronger and quickly different from himself during the performances. The smell of the masks, for instance, conveys a specific energy that penetrates his body, helping him to transgress the usual boundaries between humanity and animality.

Preah Kunlong opens the path toward an intuitive understanding that Zhuangzi described as a ‘non-knowledge’, aknowledge that would encompass what cannot be rationally known, freed from any intentionality.[23]The Chinese philosopher is particularly interested in the tipping point when the body, artificially controlled by the mind, starts operating by itself. During this changeover moment, the consciousness is released, and something else is taking over, something seems to be superior, more complete, spontaneous and natural.

|

| Leeches on Nget’s foot.Documentary photograph. Courtesy of the artist.

|

Similarly, and despite the difficult working conditions on site, humidity, tiredness or leeches and teeming insects, Rady began to feel and behave differently as soon as he wore the mask, leaving his mind aside and trusting only his body’s intuitions. Literally, he let everything go, and his performance is a perfect expression of a spontaneity freed from the human will and intention. Like the sleepwalker who knows what to do even though he is sleeping, he trust his body knowledge which he has accumulated with years of practice as a dancer of Lakhaoun khaol,when he played the monkey character.[24] From this empiricist perspective, the conscious can indeed disappear as one is able to“espouse the metamorphosis of reality” and to evolve freely.[25] In Preah Kunlong,Rady resembles the swimmer who abandons himself to the flow of the stream without any fear,depicted by Zhuangzi as an accomplished man. In this famous dialogue,Confucius sees a man who dives into the water, said to be too dangerous for anyone to swim.[26]He who is supposed to know everything is astonished to discover that this man can swim there so easily, and he asks about his secret. There is no method, replies the man, “I have no way”. I simply “go under with the swirls and come out with the eddies, following along the way the water goes and never thinking about myself.”[27]In the same way, Rady has no method: he only followed his way, just like the animals and the spirits of the forest, and the film is taking us with them on this original path.

A metaphorical performance

Khvay’s camera and plans follow and magnify Nget’s performance, transcending the specific context of the Areng Valley to bring forth a renewed conception of nature and of our way to inhabit the world. Against an official discourse praising progress and development, Preah Kunlong opposes images of a pristine place that seems to speak for itself, only troubled by the movements of the hybrid dancer. Amirage of beauty and intuitions poised to resist the irrational and invasive world of techniques and investments.

Perhaps the most striking element of the film is that there is no direct reference to the Chong people and that it features no animals either: Khvay offers us a metaphorical representation of what he saw and felt in the Areng valley, converted into the sensual language of art. His process of work could be compared to the practice of work of ancient Chinese painters who never searched to paint reality, but to represent how this reality affected their inner self and imagination.

The editing work strengthens and extends the metaphor: the dancer continuously jumps from one screen toanother, creating for instance a sense of continuity within discontinuity. Similarly, we do not witness the changes of the masks, or the transformation’s states between the different animals: despite multiple transformations, Nget makes one with nature and with the animals, perceived as an ontological entity.

|

| Khvay Samnang, Preah Kunlong (2017) Digital C-Print, 80 x 120 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

|

When the film starts, Nget is already standing in the left screen. He can be seen from afar against the backdrop of a mighty waterfall whose noise pervades the gallery space. He wears the mask of the deer. We feel that he has always been there, and is a smallp art of a vast, pristine and beautiful landscape. On the right screen, we can see him closer, lying on the top of the waterfall, wearing another mask – this time of the crocodile. He unhurriedly stands up, as if waking up, extending his muscles one after the other. He faces the landscape, but is also above it. Dominating nature and simultaneously being dominated by it… the duality of the images constantly negates traditional oppositions and proposes a continuumthat, instead, expresses a solidarity between all the elements involved: time,nature, space, animals and dancer, all connected and deeply united.

The viewer either observes the dancer or sees what he sees and, therefore, becomes the dancer/animal himself. This sense of fusion is reinforced by the sensuality of the framing and editing. Khvay’s direction alternates between close-up shots, which linger ondetails of the dancer’s movements, skin and muscles, and wide-angle views ofthe environment. Mud, soil, water and vegetation are intimately sticking to the dancer’s body. Jerky rhythms alternate with static plans. In the middle of the film, Nget starts to growl and squeak, mixing his voice with the sound of the environment, blurring again the boundaries between humanity and animality.[28]

What resembles a mythology resonates with contemporary and global ecological concerns. At the end of the film, the dancer abruptly disappears, before it starts again as a loop. This sudden vanishing embodies today’s disappearance of the tradition and culture of the Chong people, as perceived by the artist, but it also represents the current rupture that divides the humans and non-humans, the former being cut off from nature by modernity, naturalism and capitalism.

|

| Khvay Samnang, Preah Kunlong (2017) Digital C-Print. Courtesy of the artist. |

Conclusion

As we have seen, Khvay’s research process of work is above all intuitive and embedded in his fieldwork’s experience. As such, Preah Kunlong is all but didactic since there is no evidence of the artist’s research findings: what he learnt from his long relationship with Chong people and from his experience in the rain forest has been totally converted into a sensual and artistic language. From this perspective, the work opens the path toward a more empirical form of knowledge, based on intuition and affect as well as on the performative language of signs. We feel that the dancer has been touched by grace, and that Samnang has been the mediator of such an almost magical arising. Preah Kunlong functions thus like a revelation, in the Heideggerian sense of a disclosure of the Being. For the philosopher, art is precisely what can operate such a disclosure and what can give us access to the hidden essence of things. “The artwork opens up, in its own way, the being of beings.”[29]

Hence, and beyond its research component, Preah Kunlong invites us to follow the artist and the dancer’s way (the way of the spirit perhaps?) in order to reconnect with forgotten forms of knowledge that we probably knew in our childhood.Ultimately, the works invites us to de-learn what we have learned before and to accept the experience of the unknown.

[1] See in particular Lopez A.(Comp.) MWBP working papers on Mekong populations of the Siamese CrocodileCrocodylus siamensis. MWBP. Vientiane, Lao PDR, 2006.

[2]The CambodianDaily, Feb. 4, 2015 (https://www.cambodiadaily.com/news/hun-sen-defends-proposed-areng-valley-dam-77352/).

[3] A Mar. 15, 2017 articlefrom the Cambodia Daily entitled ‘NGO Wary of Promise to Cancel Hydropower DamProject’ suggested that there are still doubts about the future of the project.(https://www.cambodiadaily.com/news/ngo-wary-of-promise-to-cancel-hydropower-dam-project-126565/).

[4] According to the reportfrom the ‘United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues’ Sixth session,New York May 2007 (https://www.un.org/press/en/2007/hr4916.doc.htm).

[5] On this point, see inparticular IndigenousPeoples/ethnic minorities and poverty reduction in Cambodia(Philippines: Environment and Social Safeguard Division of the AsianDevelopment Bank, 2002), 9-10.

[6] See for example thereport from the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues Sixthsession, New York May 2007. https://www.un.org/press/en/2007/hr4916.doc.htm

[7] Sokphea Young,“Practices and challenges towards sustainability,” in The Handbookof Contemporary Cambodia ed. Brickell Katherine and Springer Simon(Routledge, 2017), 113.

[8] Strangio Sebastian,“The Media in Cambodia,” in The Handbook of Contemporary Cambodiaed. BrickellKatherine and Springer Simon (Routledge, 2017), 76.

[9] See in particularSutton Jonathan, “Hun Sen's Consolidation of Personal Rule and the Closure ofPolitical Space in Cambodia,” Contemporary Southeast Asia: A Journal ofInternational and Strategic Affairs, 40, 2 (Aug. 2018):173-95.

[10]MorrisCatherine, “Justice Inverted,” in The Handbook ofContemporary Cambodia ed. Brickell Katherine and Springer Simon(Routledge, 2017), 29.

[11] See in particular theassassination of famous activist and political commentator Kem Ley on 10 July2016, but closer to Preah Kunlong’s ecological topic, Morris relates thecase of an environmental activist investigating illegal logging who was killedin Koh Kong province in 2012. See Morris, “Justice Inverted,” Ibid., 35.

[12]Strangiounderlines the pressure under which the reporters have to work, often beingthreatened or bribed. See Strangio, “The Media in Cambodia,” ibid. 82.

[13] Corey Pamela N. UrbanImaginaries in Cambodia In: Catalogue connect: Phnom Penh: RescueArchaeology Contemporary Art and Urban Change in Cambodia edited by ifa-Galerie(Berlin Germany 2013), 117

[14] From d14 Floor Labelduring Documenta, courtesy of the artist.

[15] According to theartist. It is difficult to have data about the Chong people. An April 2018Phnom Penh Post article mentions 200 families living in the Koh Kong province(Available at: https://www.phnompenhpost.com/national/ethnic-areng-valley-minority-group-petitions-recognition)

[16]Sokhom, HeanEducation in Cambodia: highland minorities in the present context ofdevelopment, Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, 5:1 (2004), p.139 - DOI:10.1080/1464937042000196897

[17] Schlesinger, Joachim. The ChongPeople: A Pearic-Speaking Group of Southeastern Thailand and Their Kin in theRegioned. Schlesinger 2017 Joachim Schlesinger.

[18] See for example IndigenousPeoples/ethnic minorities and poverty reduction in Cambodia, Environmentand Social Safeguard Division of the Asian Development Bank, Philippines 2002

[19] Forest, Alain, LeCulte des Génies Protecteurs au Cambodge (the cult of guardian spirits or‘neak ta’ in Cambodia) (Paris: L’Harmattan édition, 1992), 49-50

[20] Spradley James, ParticipantObservation (Illinois: Waveland Press Inc.,1980), 3.

[21] Lopez A. (Comp.), MWBPworking papers on Mekong populations of the Siamese Crocodile Crocodylussiamensis (Vientiane, Lao PDR: MWBP, 2006).

[22] Ingold, Tim. Making:Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture. Routledge, 2013, 1.

[23] Zhuangzi, TheComplete Works, trans. Burton Watson (New York: Columbia University Press,2013).

[24]Thistraditional theatre requires a long experience of training for the dancer to beable to feel and act like the interpreted animal and is mainly based ongestures as language since none of the animals speaks. For more on Cambodiantheatre see in particular “A conversation with Pring Sakhon (Oct. 03, 2001)” inDaravuth and Muan Cultures of Independence (Phom Penh, Cambodia: ReyumPublishing 2001), 133-34.

[25] I follow here theinterpretation of the text by Jean-François Billeter, notably In BilleterJean-François. Leçon sur Tchouang-Tseu (Paris: Allia, 2010).

[26] Zhuangzi, TheComplete Works Ibid., 151.

[27] Zhuangzi, Ibid., 152.

[28] The description of thework comes from a previous article. See Ha Thuc Caroline. “Khvay Samnang: TheWay to the Spirits.” CoBo Social magazine, Sept. 2018. Available at: https://www.cobosocial.com/dossiers/khvay-samnang-the-way-to-the-spirit/

[29] Heidegger, Martin. “TheOrigin of the Work of Art” In: Heidegger Martin, Off The Beaten Track,edited and translated by Julian Young and Kenneth Haynes (Cambridge UniversityPress 2002), 17.