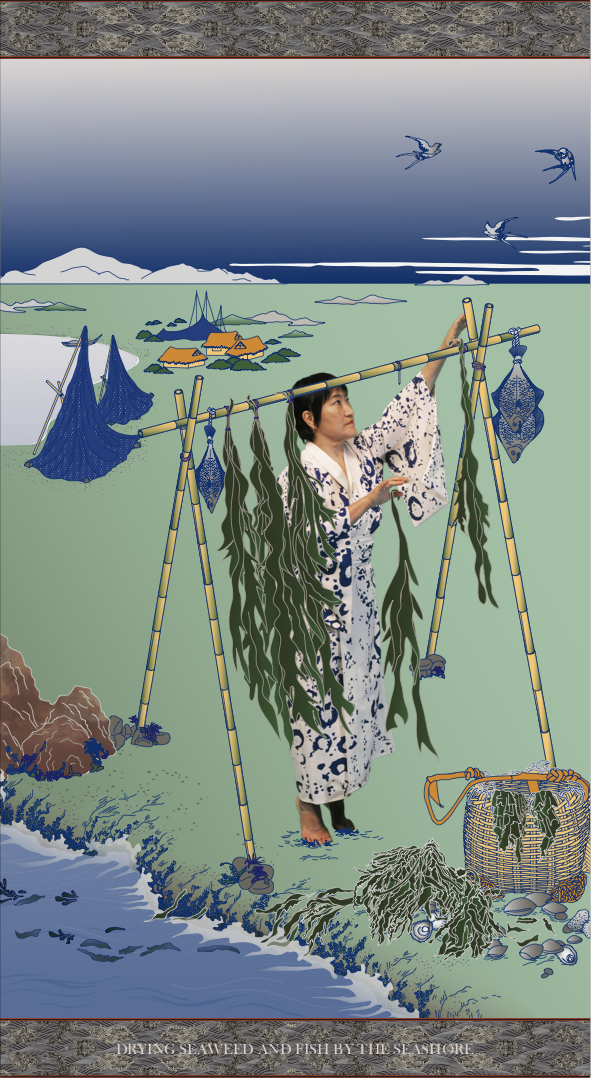

Engine – 20KM, variable matrix of 20 photographs

View of the exhibition at The Guild, Mumbai, India 2025.

All images courtesy of the artist and the Guild Art Gallery

Else All Will Be Still is an ensemble of works, mainly photographs and videos, derived from Ravi Agarwal’s long-term fieldwork among fishermen in a small coastal village of Tamil Nadu, India.[1] The series offers a multitude of perspectives from which to grasp the complex reality of this community whose traditional way of life is bound to disappear. The work focuses on the fishermen’s work techniques and daily gestures, and emphasizes their specific relationship with the local ecosystem. At the same time, Agarwal proposes a deeper reflection on the unfathomable nature of the sea and shares his own experience and attempts to capture its inexhaustible features.

Born in 1958 in India, Ravi Agarwal is an artist, a documentary photographer and an environmental activist. His pluri-disciplinary practices overlap and complement each other and aim at addressing today’s ecological crisis and environmental injustice. Else All Will Be Still belongs to the artist’s long-term questioning process about the idea of nature and reflects his quest for new paradigms that would reshuffle human and non-human relationships. In particular, it points to labour and technical objects as ambivalent modes of interaction between individuals and their environment.

For this series, Agarwal drew on an early form of Tamil poetry in which landscapes are associated with inner human feelings in an inclusive conception of the world. In contrast with today’s fast changes that radically transform the environment and traditional livelihoods, these poems inscribe the artworks into an ancient era and invites viewers to apprehend those mutations within a much longer period of time and through the lens of another culture. Combining written or recited verses with visual images, from documentary video to constructed photographs, the artist explores and questions the ability of any form of language to capture an increasingly complex reality. With its open-ended, fragmented, non-didactic and heterogeneous format, Else All Will Be Still reflects Agarwal’s attempts to open-up the field of knowledge and to think anew about the given frameworks of modernity.

Contextual framework and artists’ drive

A long-standing and on-going ecological activism

Alien Waters, photographic print, 2004.

“Art can play a critical role. Artists through embedding their practice in the ecological discourse and collaborating with other practitioners can foster fresh interdisciplinary understandings of the entangled questions of ecology.”[2]

Ravi Agarwal grew up on the banks of the Yamuna river, a 1,300km-long river that cross the megalopolis of Delhi. With his camera – he had his first one at the age of 13 and, since then, has always kept it with him - he observed the changes of its waters, its ecosystem and environment, recording its deep degradation as a result of climate change and high urbanization. For decades, he documented its flora and fauna, the rise and fall of the coal-fired power plants on its banks and the life of the population living from and around it. In particular, he followed the eviction of those inhabitants, some of whom were forced to leave the land because of project developments. Many artistic projects arose from this long-term relationship with the river, from photographs of these communities in Alien Waters (2004-2006), art installation on its shores with Riverbank Installation (2007) to a documentation of marigold flower growers who work also on the river shores, Have You Seen the Flowers on the River (2007-2010).

For Agarwal, landscapes and nature cannot been conceived without addressing the question of the people living and working within their environment. The issue of labour is especially fundamental since it involves the transformation of nature but also the exploitation of resources and of people. According to the artist, “labour is just another commodity.”[3] In 1996, he founded Toxics Link, a community-driven platform and collective organization that collects and shares information about the sources and dangers of toxic substances, promotes sustainable alternatives and defends environmental justice. As an activist, he faced many court cases for “trying to speak about irresponsible corporate power and people's vulnerabilities.”[4] Besides, he has spent years documenting the lives of migrant workers, especially during his long-term project Down and Out: Labouring under Global Capitalism (1997-2000) presented at Documenta XI (2002). The series emphasizes how the landless workers of South Gujarat have contributed to the development of India without benefiting from it. In parallel, he has been writing essays about climate change and the Anthropocene, editing books and journals about art and ecology.[5]

Down and Out: Labouring under Global Capitalism, photographic print, 1997.

Before 2013, the sea was an alien element to Agarwal until he decided to study the impact of climate changes on the coast and on the lives of fishermen from a small fishing community in Tamil Nadu, in the south-eastern part of India. As we will see, many different issues collide there, bringing radical changes in this fishing village. Agarwal aims at understanding the villagers and their environment from multiple perspectives and at expressing the complexity of the situation, with a holistic approach. Art offers him the means to reflect on this multiplicity: according to him, activists, in order to be heard, need to deliver clear messages, that obviously lack nuances. Similarly, academic researchers need clarity in their expression, and are usually asked to develop relevant arguments. In contrast, and as an artist, Agarwal does not need to comply with any rule and feels free to propose something different, more open, perhaps more confused as well but, he hopes, closer to life.

Else All Will Be Still is an attempt to seize reality with its complexities and ambiguities. For him, the series is “a jumble of everything: I am not really trying to make any sense here. I am just trying to know something better, although I cannot say that I succeeded. I rather wish to reflect on my ability and inability to understand.”[6] His questions are in fact numerous: what is nature and what is the sea? How can we engage in nature differently and move away from the Western conception of nature as a separate entity? How are these fishermen coping with the environmental degradation, how could we learn from them? In his diary, which is part of the series, he asks: “What are the boundaries of ‘ecology,’ of ‘nature,’ of ‘knowing?”

Ravi Agarwal in his studio in 2018.

Sangam Poetry: re-thinking the self within nature

Agarwal emphasizes how much the life of the fishing community is entangled with the sea and notes that, perhaps, “in such entanglements could lie hidden secrets of other ways of being and re-learning how to coexist with the planet.”[7] As he was wondering how he could express such an interconnectedness, he delved more into the Tamil culture and discovered Sangam poetry through Mrs. Meenakshi Ji, a veteran master poet whom he was introduced to. This very ancient tradition, dating from about the beginning of the Common Era, is considered to be the earliest known literature of South India. The poems are mainly about love and war, but what struck Agarwal is the intimate connection made between nature and human feelings: each physical landscape is rooted in a particular mood of the human being and, conversely, human inner experiences are correlated to specific habitats. In particular, neithal, which means the sea in Tamil language, is coupled with the state of longing that arises from a long separation from the beloved one. It is also associated with water lilies, seashore, sunset, fishing and costal trade as activities. Obviously, there is a balance here between the various living elements which combine harmoniously, with nature conceived as an intrinsic part of the human life. Although most of them might not know this ancient literature, traditional fishermen valued these interrelationships and their fishing methods used to be respectful of the environment in a way which is connected to this mutual connectedness.

Such a symbiosis inspired Agarwal to rethink the idea of nature, not seen any more as a mere resource or as an object that can be exploited and commercialized. Just like the fishermen do, he wanted to learn how to live “on, off and in” nature and the sea, which is, in fact, more complicated than it seems. Fishermen’s lives cannot be romanticized and, besides, the artist was confronted with the open sea for the first time. He acknowledges that the sea he saw “was clearly not the sea they saw!”[8] and reflected on his own vulnerability and inability to grasp its essence. For him, the questions raised by nature are still not understood today. Sangam poetry and art might offer novel perspectives and epistemic frameworks to think anew about the very foundations of modern life.

Most traditional knowledges and cosmologies, in fact, are based on an expanded conception of the self which supposes a mutual solidarity between human and non-human beings. They are now increasingly recognized by ecologists and anthropologists in their attempts to reconsider the multitude of micro relations that link humans and non-humans daily and constitute essential bases to engage into political ecology.[9] In India, however, fishermen are seldom listened to, and their local knowledge is disregarded.

Artisanal fishing in Tamil Nadu: a threatened activity

Fishermen on the beach. Fieldwork photograph.

With a coastline of 1,076 km and about 600 fishing villages, Tamil Nadu is one of the most important Indian states for fish production. It also offers a very rich marine ecosystem with a high biodiversity. However, recently, the state has been facing many challenges and the traditional fishing activities are perhaps on the edge of disappearing.

New techniques of fishing are putting pressure on the local ecosystem and on the natural stock in a national (and in fact general) context of overfishing. Besides, mechanized boats compete inequitably with smaller and traditional boats and despite recent regulations, many conflicts occur between artisanal fishermen and those involved in mechanized fishing operations.[10] Traditional boats cannot venture too far from the shore, and their catch is obviously limited. In Tamil Nadu, fishermen used to navigate on kattumaram, wooden raft made from a few tree trunks tied together with fiber lashings. In Tamil language, kattumaram means "tied wood," from kattu "binding" and maram "wood.”[11]

After the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, many of these boats were replaced by fiberglass boats and, while important sums of money were dedicated to the devastated areas, the villagers were not asked about their needs. For example, some concrete housing estates were built for them, although nobody wishes to stay in such housing. According to Agarwal, they prefer sleeping on the beach. The tsunami has accelerated some radical changes within the fishing communities, with new technologies widening the gaps between a new type of businessmen and marginalized fishermen. “Along with the new boats, had come diesel engines, especially for those who were able to invest in larger boats. (…) A new hierarchy of technology access had developed within the same community.”[12] Agarwal witnessed the fishermen’s hesitations as to how their livelihood should transform and adapt to the new global capitalist society. The artist observed how much the village he stayed in had changed over these few years as tourism increased and leisure construction emerged on the beach, again without any consideration for the existing fishing activities. With tourism, the price of land soared, and many fishermen sold their place. Finally, the neighbouring town built a harbour that impacted the ocean currents, resulting in a sand erosion of the beach where the fishermen used to land.

Fishermen on the beach. Fieldwork photograph.

Just like the beach, the traditional fishing community keeps shrinking, squeezed between too many issues that increase its vulnerability. “… fishing as a livelihood seemed to be a dying one. It would survive, but as a business, not a livelihood,” notes Agarwal in his diary.[13] Some fishermen make sure that their children do not learn how to swim, so that they will never live by the sea. For the older generation, swimming was equivalent to walking, and they all learnt it at a very young age. Now, an immense gap is thus dividing the generations, with the knowledge of the oldest about to vanish. However, this knowledge and fishermen’s singular perception of the sea and of the local marine ecosystem could be very helpful to understand climate change and ecological mutations. [14] In India, the question is seldom addressed, and these small-scale fishermen have little agency regarding the decisions that are made about the development of their own land and economic activities.

As an invitation to penetrate their daily lives, to see their work techniques and to approach some of their concerns, Else All Will Be Still gives these fishermen a voice, and emphasizes their culture. According to Agarwal, the Indian modernity tends to be invasive and does not allow for periods of transitions. “The mindset in India is about moving forward without looking at the past, rather than building from what we have.”[15] The artist calls for a more evolutive conception of modernity and of progress that would include traditional know-how and local contexts while considering the interconnections and mutual solidarity that link the self and the environment. In his work statement, he expresses the urgency to do so: “the works are an outcome of my struggle to comprehend the times we inhabit. Fishermen friends helped me navigate new waters.’ The ever changing, ever moving sea led me to these explorations. There is urgency in the air. Else, all will be still.”[16]

The artist researcher

Fieldwork: living with fishermen

The series began by chance when Agarwal was visiting friends who live near Pondicherry. After interacting with the local fishermen, he wished to know more about their local ecology and about how they were affected by climate change. He decided to spend more time on the coast and rented a fishing hut in a village named Thanthirayan Kuppam. He would spend 2 to 3 weeks there, from time to time, between October 2013 and August 2015. For him, it was essential to share the daily life of these fishermen in order to better understand their concern, their culture and traditions, and in particular their relationships with the sea. Reading about their landscape and communities was indeed not enough to really grasp the complexity of their reality.

Ravi Agarwal fishing during his fieldwork

Progressively, he became friends with the local fishermen and in particular with one of them named Selvam. He went with him several times on his fishing boat and learnt about some of the traditional fishing techniques. In the morning, he used to follow some of their activities on the beach, watching the catch of the day and the fixing of old boats. He met an old man who came every morning and spent hours contemplating the sea. This man had lost one of his leg during an accident and, when asked about his daily habit, he replied that the sea was all he knew. Besides, Agarwal observed their festival and how they pray the goddess of the sea, or practice idol immersions in the sea. The artist does not speak Tamil, so sometimes there were some translation issues with the local people, yet he managed to communicate with most of them using English or Hindi.

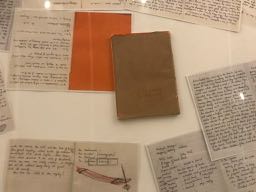

Ravi Agarwal’s diary and notebook

We can follow the artist’s journey thanks to his diary, which is exhibited alongside the artworks. Agarwal noted his thoughts, descriptions of the boats, of the beach and of its evolution, but he also noted down the stories he collected from his conversations with the local people. In a very personal and sometimes poetical manner, he wrote down their dreams, their doubts and their wish to give their children a better future, far from the sea. The artist related a few anecdotes as well, such as when the fishermen tried to resist the expansion of tourism, resulting in fights and arguments with businessmen running a hotel. On the first two pages the artist has written words related to the fishermen’s perception of the sea, noted while discussing with them. This gave birth to the photograph Rhizome (2015) and reflects the pragmatic vision that they have from their environment: subsidy, sickness, cyclone, monsoon, jellyfish… What struck Agarwal is that there were no conceptual/abstract words. When they relate to traditions, for instance, they refer to festivals, temples but not to their traditional knowledge.

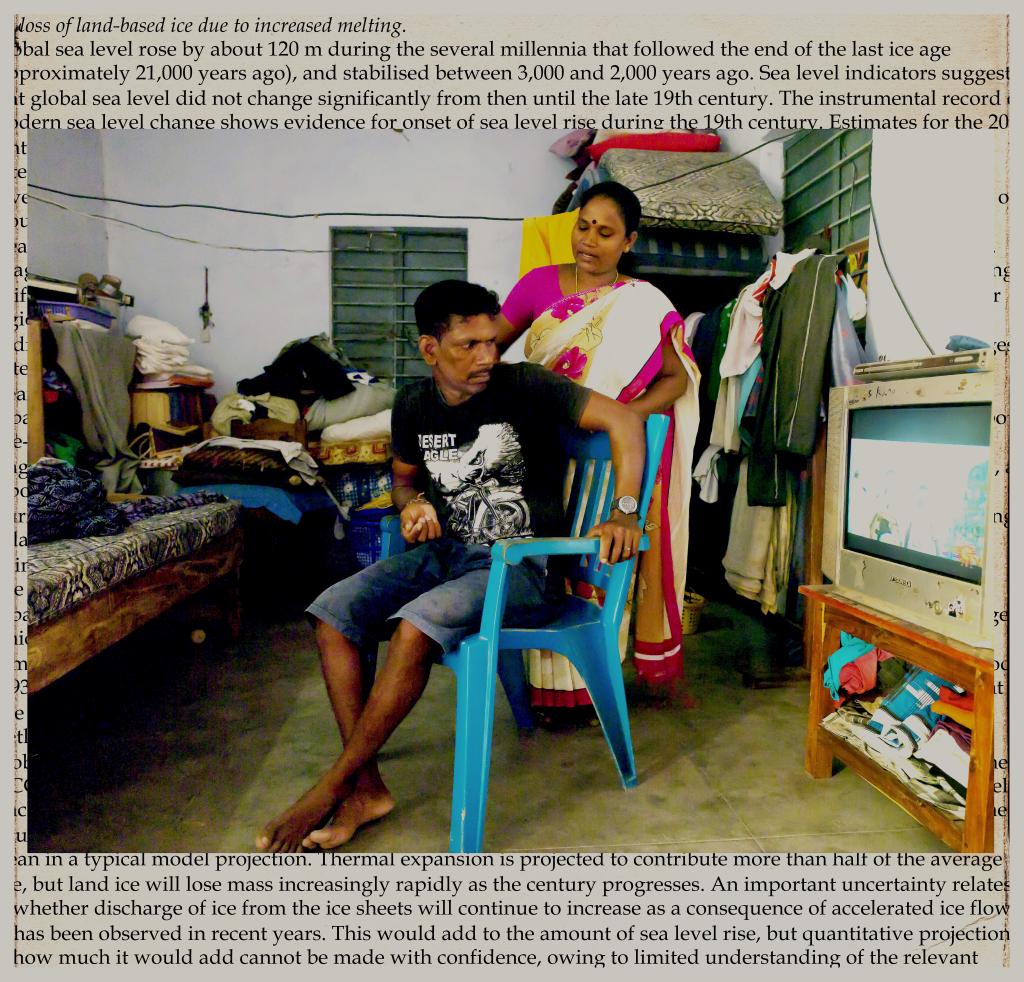

No One Asked Me, archival photographic print 17 x 17cm, 2015.

Besides collecting stories, Agarwal took many photographs of the fishermen, yet many of them are not displayed. In fact, Else All Will Be Still does not directly address the daily life of these fishermen. Some photographs are shown inside the diary, but otherwise he chose to keep his distance with their personal life. For him, there is an essential difference between the artworks hung on the wall or installed on the floor, and the diary that viewers have to browse, which he considers a mere documentation. Documentary photography was Agarwal‘s first medium and, for him, the question of the representation of others has always been delicate. He confesses that some photographers such as Brazilian social documentary artist Sebastiao Salgado, have found their way to represent other communities through their work, but it is not yet the case with him. He remains wary of stereotypes and of the relations of power implied by the representation of others, thus he always hesitates about showing the fishermen as persons. It might be also a way to protect them. Therefore, in this series, he only displays one photograph featuring Selvam and his wife in their home, entitled No One Asked Me (2015). This is a very formal photograph, taken following a very ritualistic procedure. As such, Agarwal does not feel that he reveals too much about their intimacy. Most of the works from the series feature landscapes and engines. Selvam is only filmed in Agarwal’s videos Shoreline I, II & III (2015), but the work focuses on his gestures and the fisherman does not express himself and remains silent. In his diary, Agarwal does not name the fishermen either, who are referred to as “he,” or who feature in photographs without being identified. This is not to keep their names secret but a way to expand their individual stories to the larger collective group of fishermen. All the fishermen and people he interviewed are thanked in his acknowledgement, though, and Agarwal showed them his artworks so that they could understand, in turn, what he has done during his fieldwork. In order to get them involved, he also invited Selvam and his family to participate in a debate with environmentalists in Pondicherry in the framework of the Pondy Photo festival in 2016.

Selvam and his family with Ravi Agarwal in front of Agarwal’s installation for the Pondy Photo festival in 2016.

A holistic approach

Despite a research process based on fieldwork, and on a long-term immersion among the community of the fishermen, with whom he established strong relationships - he continues to talk to them regularly over the phone nowadays - Agarwal is thus not working as an ethnographer. If we consider, with French anthropologist Marc Augé, that the subject of study in ethnography is the alterity and the question of the other,[17] the artist seems precisely to avoid such an object of investigation. On the contrary, he purposely and continuously claims his personal interpretation of the reality he is observing and does not propose to depict all features of the fishermen’ way of life. Somehow, he tries to give these fishermen a voice without directly representing them. Besides, his research process is intuitive and does not follow any systematic methodology. He rather brings forth a patchwork of elements that he presents to the audience as an invitation to compose their own vision of the Tamil coastal communities and of the complex ecological issues that coalesce there. As he was traveling along the coast, he noticed for instance immense salt pans near Pondicherry, which he found fascinating. For him, these landscapes embody the industrialization of the coast and large-scale extractive industries. A large photograph entitled Salt Pan (2015) belongs to the series and does not directly relate to the fishermen community. However, for Agarwal, all these elements are linked as they contribute to alter our environment, and thus our relationship with nature through labour and resources exploitations. The artist investigated as well the amount of micro plastics he could find on the sand, and which might impact the quality of the salt extracted, yet he did not include this part of his research in the series.

Salt Pan archival photographic archival print, 36 x 103 cm, 2015

Agarwal’s fieldwork, like his practice, is holistic and his approach is pluri-disciplinary: he is concerned with the economy, culture, politics, history, literature etc. because ecological issues cannot be addressed without embracing all these dimensions which constantly overlap and mingle. Through his network of environmental activists, he was for instance introduced to PondyCAN, a non-profit organization based in Pondicherry. Their members work with the local communities and collaborate with the Indian government, researchers and the civil society in order to bring ecological changes on the Indian coastline.[18] One of the artist’s interview with Aurofilio, who co-founded PondyCAN in 2007, features in the series as a 36-minute-long video entitled Sea of Sand (2015). Aurofilio is specialist of waste water treatment and he has been working on the restoration of the Pondicherry coast. During this specific interview, he discusses the issue of the building of the port nearby the village, and the disappearance of the beach. For the artist, it was fundamental to hear such a voice and to confront various perspectives on the situation. Agarwal met also Meenakshi Ji, the veteran master poet mentioned above. He recorded their interview but he could not use it because of a glitch.

Sea of Sand video (36 min), 2015.

Agarwal supports his ideas, questions and theories with many academic references. In his essays, he draws in particular on Gilles Deleuze’s notion of the rhizome, a subterranean structure which develops and unfolds horizontally like the roots of a plant through infinite ramifications.[19] This notion aptly reflects Agarwal’s series of works presented as an inclusive constellation of texts, images and sounds and the artist’s attempt to connect heterogeneous elements conceived from different perspectives. Agarwal’s questioning of the idea of nature is notably inspired by theorist Timothy Morton and by Indian philosopher Akeel Bilgrami, especially for his analysis of Gandhi’s philosophical thoughts,[20] yet his scholarly sources are very diverse, from Western philosophy to Indian cosmology, Buddhist theories and literature. He cites for instance Indian writer Amitav Ghosh, who recently addressed the issue of climate change in non-fictional essays, art historian T.J. Demos with whom he collaborated and historian Mark Cioc, known for his environmental and historical study of the Rhine.[21] For Else All Will Be Still Agarwal read articles about contemporary fishing practices in Tamil Nadu, translations of Silappathikaram, an ancient Tamil epic mentioned in the Sangam literature, and various translations and commentaries on Sangam poetry.[22]

Artistic transformations of the research findings

A rhizomatic network

Else All Will Be Still unfolds into a profusion of various artworks that could be classified according to their main topic: a first set deals with the sea as an unfathomable element; a second set focuses on the fishermen’s tools, engine and techniques; a third presents some background context about the situation of Tamil fishermen today and, finally, a last set proposes fictional and poetic perspectives on all the above issues. All these artworks complement and dialogue with each other. The figure of a rhizome could indeed describe this composite ensemble that forms a very free network of artworks juxtaposed without any specific entry point or order. Implicitly, the artist invites the audience to link the breath of the ocean with fishing nets, boat engines and traditional fishing vessels and to critically question the nature and evolution of these links. Further, he suggests to rethink every identity in connection with these entities, extending them through their mutual relations.[23]

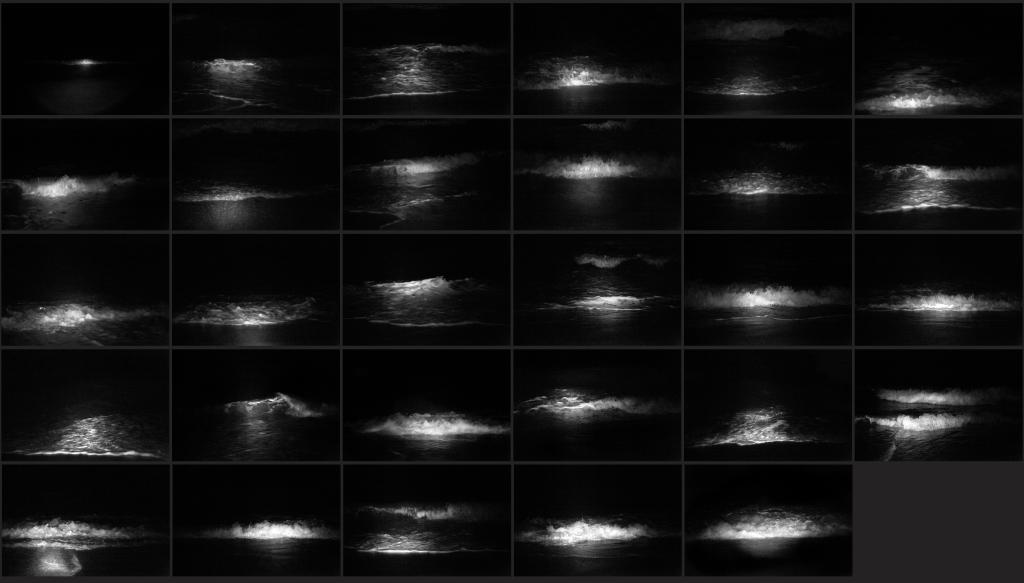

Lunar Tide, archival photographic prints, variable matrix of 29, 17,5 x 26,5 cm each, 2015.

Lunar Tide (2015) is a series of 30 photographs taken at night and juxtaposed in a large composition. Agarwal used a lamp torch to shed light on the waves as they burst on the shore. At first, he was inspired by the silver lines drawn by the moonlight on the sea surface and he tried to mimic them. The title of the work reflects this ambiguity: we cannot guess if the spotlight comes from a natural source or from a technical effect. The work suggests that despite today’s technology, we cannot see what is beyond the surface or that technology did not provide us the keys to this natural and mysterious world. In fact, this inability derives from the relationship of human beings with nature, conceived as an external landscape that needs to be controlled and deciphered. Another reading of the work could switch this perception around: the whole composition evokes a series of x-ray photographs in which the lighted part of the sea would represent an embryo in its first stage of development. The night would then become a womb that would give life to the waves, just like women give life to babies. From this more ambivalent perspective, the sea and human beings become ontologically emmeshed.

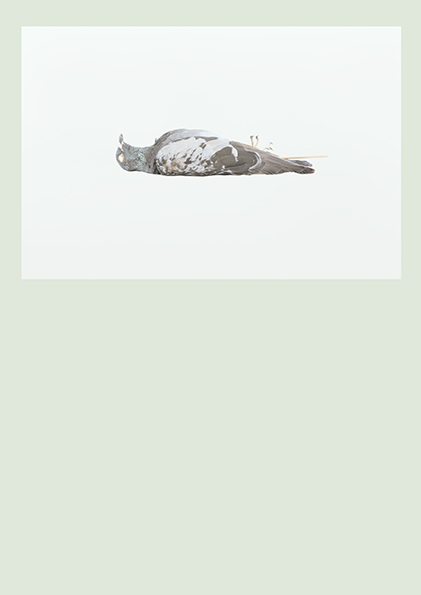

Like Lunar Tide, the 5-minute video Neithal features the sea, shot at night and only partially lighted by a white torch. It is structured almost symmetrically with a climax in the middle of the video. In the beginning, the surface of the sea can barely be seen but the sound of the waves pervades the space. This powerful noise is soon amplified by a regular pulsation similar to a sonar that seems to punctuate the invisible movements of the waves. Then, like a crescendo, the artist’s voice merges to the ensemble. It recites some Sangam poetry but is constantly disrupted, with each word being repeated like an echo. Finally, more voices join what resembles then a choir, all of them reading news about climate change extracted from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP)’s websites. These voices are so loud that the sound of the waves is now inaudible: the images of the sea serve only as a mere background for these interwoven discourses. However, by the middle of the video, a decrescendo arises: the voices are reduced and the waves swell again in a reverse tendency. In the very end, though, the audience is left facing a silent sea. Technique and discourses seem here to combine in an attempt to elucidate the environment and climate changes. However, they remain external to the nature they probe or describe, maintaining the gap that separate human beings and their environment.

4am, matrix of 64 photographs, 2015.

In contrast, some artworks suggest a more inclusive approach. 4am is a set of 64 colour photographs featuring the dark silhouette of the fisherman while he drops his net from his boat at dawn. They are arranged chronologically and, from the upper left to the bottom right, the light changes with the sunrise, turning slightly pink with golden hues. The blurriness of the images transcribes the constant movements of the fisherman, paddling, pulling in and out the net in blacklight. His body seems to merge with the elements and to espouse their dynamic: dancing with the waves, moving with the clouds, rising with the sun… When juxtaposed with the artworks featuring the open sea, this composition emphasizes the deep connexion that binds fishermen with their environment through a multitude of relations.

In-between the man and the sea, or forming a fundamental trio with them, are the fisherman’s tools, his boat and engine. In the series, the role of technique as an intermediary between human beings and their environment is striking. Ultimately, labour appears as the way to interact with nature and, more specifically, with the sea. A trilogy of videos is dedicated to particular fishing techniques: the art of dropping a net in Shoreline I; the art of building a traditional kattumaran in Shoreline II and the art of mending a fishing net in Shoreline III. These videos are mostly silent, except for the ambient noise. Favouring long and steady shots, the camera follows Selvam, the fisherman, in his daily routine, focusing on his gestures. The subject of these works is not Selvam but the nets, the rope, the wooden trunks that constitute the boat, and the fisherman’s hands which transform these materials into objects of technique. Shoreline III, for instance, takes place near the beach yet the video does not provide any contextual background. We only hear the chirping of birds, the horns of cars and voices from afar. It begins directly with a close shot of the fisherman’s skilful hands while he repairs his net. We discover the thread and the long needle he uses and follow his very precise and fast gestures. Later, a few larger plans show him with a pile of enmeshed nets. He pulls them back to gather them, probably preparing for fishing. They look immense as if they could not end. Surprisingly, in these videos, we never see any catch nor any fish and we do not know anything about this fisherman, as if these scenes had been extracted from the reality. This focus exacerbates his solitude while the very slow pace of the work and the repetition of his movements locate his gestures into a timeless period, connecting him to his ancestors. Selvam seems here to represent all the fishermen, not only from his generation but from all times, who patiently transmitted and skilfully carried on with these gestures. This tradition echoes an immutable reality that strongly opposes today’s radical transformations and the vulnerability of this community. Implicitly, Else All Will Be Still creates a tension between these images of stability and a contemporary world on the verge of collapsing. The photographic composition Engines 20 KM alludes to this impossible transition: it features 20 close-ups of colourful boat engines made from recycled material and tinkered ingeniously. This handiwork embodies the pressure of today’s fishing activities, with the need to go further and faster, and the dreams of the fishermen to own better boats and access better catch, and a better living.

Shoreline I, video (18 min 46 sec), 2015.

Despite these underlying tensions, however, none of the artworks is violent or tensed by itself. On the contrary, they are all imbued with a form of serenity and their tranquil beauty seems to defy these contemporary challenges. The rhizomatic composition of the whole series, with its great freedom of association, offers a fluidity of approach that leaves room for a multiplicity of links to arise, and transversal interpretations to emerge. Agarwal does not intervene in any of these readings and remains distant, maintaining here, it seems, the same distance he nurtured with the fishermen. His series is thus paradoxically highly personal because of his choices of subjects and encounters, and neutral in its exposure.

A poetics of languages

Sea of Mars, archival photographic print, 29 x 47.5 cm (Original photograph NASA), 2015.

From mere documentation to constructed photographs, Agarwal plays with the large scope and ambiguities of photography and video as mediums, moving seamlessly from one realm to another. In particular, photography and moving images allow him to navigate between the past and the present, fiction and reality, or memory and imagination, introducing purposely some confusion in the interpretation of the works. In contrast with the documentary works described above, Else All Will Be Still features as well a series of staged photographs that displaces the Tamil context into fictional spheres. In the photograph Sea of Mars, for instance, an abandoned kattumaran lies on the rocky ground of a deserted landscape. The sea might have carved the geological patterns of these mountains and valleys, on the planet Mars or here, yet it seems to have withdrawn long time ago. The black and white image evokes an archival photograph which could describe a bygone era or prefigure a time to come. In fact, it originates in the NASA archives. In all cases, the useless fishing boat becomes the symbol of a lost and obsolete culture but also of its resilience: when nothing survives, the boat lives on.

Rhizome offers another example of such a drifting between reality and fiction: Agarwal collected the words that fishermen associate with climate change, and wrote them down on labels that he planted on the sand. The photograph illustrates the outcome of the artist’s performance. With the sea at the background, though, these placards also resemble property titles except that they do not describe any ownership but manners to live with and on the shore. They could even be read as protest boards held by the sand/land itself, whose voice is never heard. At the same time, the written words, incarnating civilization, seems to invade the beach while pretending to voice for it. Who is claiming rights, here? Christopher Stone, who is among the first ones who question the possibility of considering non-humans such as trees as legal subjects, suggests that nature, just like indigenous people, might soon claim rights. [24] Who can claim the ownership of a disappearing beach, and who is liable for its degradation?

Rhizome, archival photographic print, 31.5 x 47.5 cm, 2015.

Far from these open-ended artworks, the 36-minute-long video Sea of Sand stands out for its straightforward documentary perspective: the work features a long interview of one of the co-founders of PondyCAN, Aurofilio, shot in his office. It begins abruptly without any question on the behalf of the artist, as if the conversation had already started and as if the audience knew about the context of the discussion, which revolves around the negative impact of the construction of ports on the environment. There is no editing work. The material is dry and not conceived to be attractive. This video confronts directly the audience with the harshness of reality yet this harshness is presented through a discourse in an office and appears thus filtered and almost attenuated.

Words, and texts, are ubiquitous in the series, yet they do not embody any anger or any revolt against the dramatic situation of the community and its endangered ecosystem. In particular, Sangam poetry, which originally connect landscapes and inner feelings, functions like a thread that binds the works together and transposes the series into the poetic realm. The extract “evening has come, soon darkness too will close in” appears in many artworks, often juxtaposed with the recurring pattern of the wooden kattumaran. The verse is also structuring the artist’s diary and it was written on the floor of the gallery’s entrance when the series was first exhibited in Mumbai. Beyond an evident and general feeling of loss and nostalgia, the interweaving of various languages and the prevalence of poetry in the series suggests an invitation to expand our vision of the world in order to include its poetic, imaginary and emotional dimensions. It is perhaps only by including these unexplored realms that a more comprehensive understanding of today’s reality can emerge.

Sangam Engines archival photographic print set of 5, 15.5 x 23 cm each, 2015.

Sangam Engines proposes such a twist in language. The series of 5 colour photographs represents specific parts of the motorboat, each one associated with one of the five Sangam concepts or words. Kurinji, or mountains is for instance written, like a caption, on a representation of an orange, rusty connecting box while mullai, or forests, is juxtaposed to a set of oxidized gearwheels. The engine parts have been photographed against a neutral background, and thus appear totally decontextualized. Their association with landscapes and feelings is an attempt to humanize or naturalize them. Here, Agarwal raises the question of the ontology of technical objects, and their place within our environment. For the artist, machines are beautiful and alive. However, they also represent the tip of the iceberg of a political economy of desire and of a capitalist system that pushes toward accumulation and resources depletion. By integrating machines within the inclusive Sangam concept of life, the artist proposes to move away from the usual alienating relationships that they imply, echoing French philosopher Gilbert Simondon’s critical approach of technical objects and his attempt to bestow them with the same ontological status as living being.[25]

Conclusion

Else All Will Be Still plunges the audience into an interconnected and rhizomatic ensemble of artworks depicting a community and a culture caught up with radical transformations and increasing pressures from the society it lives in. From technical details about ports planning to fishing skills, ancient poetry and climate change, Agarwal tackles the issues from multiple viewpoints in order to reflect the complexity of the situation, and the necessity to consider it from a pluri-disciplinary perspective. Besides, the artist’s exploration of diverse modes of documentation and languages suggests the need to embrace a plurality of mediums and languages in order to enlarge our understanding of the reality, including the use of fiction and imaginary settings.

Agarwal’s process of work escapes any systematic approach and his research outcome and artistic creations reflect this free and experimental mood. The artworks of the series are not dogmatic and remain purposely open to different interpretation. Aside from a short statement, and from his personal notes written on his diary, the artist does not guide the viewers who have room to reflect critically on the works. Consequently, the knowledge generated by the series remains incomplete and fragmentary. This indeterminacy arises as a necessary consequence of the poetic and aesthetic dimension of the works. It leads to a form of “opacity” or critical confusion, which is claimed by many post-colonial thinkers as a means to challenge the scientific rationality that, for a long time, has established the frameworks of knowledge production.[26] The series Else All Will Be Still does not produce new sets of dogma, but initiates dialogues rendered even more necessary by the indeterminacy it creates. This larger and more open framework leaves to the viewer the responsibility to re-appropriate and consolidate the new forms of knowledge it generates. The series could be conceived as an initiation, an invitation to penetrate the world of these fishermen and to think anew, with them, about our daily interactions with nature from a more collaborative, ethic and mutually respectful perspective.

The very serene tone of the series, and its apparently tranquil opposition to the fast degradation of the environment and of the fishermen’s livelihood could echo Gandhi’s politics of non-violence conceived to get back India’s independence in the 1930/40s. Akeel Bigrami, who analyses Gandhi’s philosophy, recalls that non-violence originated in part from Gandhi’s desire to see the British leave the country by means that were not derivative of their systems of thoughts in order to free the Indian population from their cognitive enslavement.[27] Similarly, one can wonder if Agarwal, here, suggests to resist the negative effects of the capitalist system not by transforming it from inside but by upending our vision of the society we live in by means that would be radically alien to such a system, namely a poetics of knowledge.

Raft installation in the gallery

[1] The series was first exhibited as part of a solo exhibition at The Guild art gallery in Mumbai in 2015.

[2] Agarwal Ravi, “Alien Waters,” in The Routledge Companion to Contemporary Art, Visual Culture, and Climate Change, ed. By Demos, Scott and Banerjee (Routledge, 2021), 374.

[3] From the artist’s website in his page related to the series Mechanical Man + Metal Man (2008)

https://www.raviagarwal.com/2018/01/23/mechanical-man-2008/

[4] T.J. Demos, “The Art and Politics of Ecology in India, A Roundtable with Ravi Agarwal and Sanjay Kak,” Third Text (27(1), 2013): 151-161.

[5] See for instance Schippert Helmut, Matzner Florian and Agarwal Ravi (ed.), Embrace our Rivers (Kerber Verlag, 2018); Lopez Paulina and Agarwal Ravi, “The Possibility of Acting in Climate Change: a Gandhian perspective,” IIC Quarterly 2019/20.

[6] Phone interview with the artist from Delhi, India, May 3rd, 2021.

[7] Agarwal Ravi, “Introduction” in Weather Report – The Crisis of Climate Change ed. Agarwal Ravi and Goyal Omita India International Centre, Winter 2019-Spring 2020 Vol 46 (3;4): 1.

[8] Agarwal Ravi, “Alien Waters,” in The Routledge Companion to Contemporary Art, Visual Culture, and Climate Change, ed. By Demos, Scott and Banerjee (Routledge, 2021), 371.

[9] See for example Descola Philippe, “Human Natures,” Social Anthropology/Anthropologie Sociale 17, 2 (2009); Kohn Eduardo, How forests think: Toward an anthropology beyond the human (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013); Viveiros de Castro Eduardo, Cannibal Metaphysics. Ed. and trans. Peter Skafish. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014).

[10] In 1983, the government introduced the Tamil Nadu Marine Fisheries Act. “The primary objective of this Act was to regulate fishing activities, especially to avoid competition in resource exploitation, as well as to solve problems concerned with the negative impacts of the gears employed by the mechanised sector.” Murugan Arumugam and Durgekar Raveendra, Beyond the Tsunami: Status of Fisheries in Tamil Nadu, India: A Snapshot of Present and Long-term Trends (Bangalore, India: UNDP/UNTRS, Chennai and ATREE, 2008), 3. However, according to the authors of the report, the conflicts continue to occur.

[11] Pohl Henrik, “From the Kattumaram to the Fibre‐Teppa—Changes in Boatbuilding Traditions on India's East Coast,” The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 36.2 (2007) : 382–408.

[12] Agarwal Ravi, “Alien Waters,” in The Routledge Companion to Contemporary Art, Visual Culture, and Climate Change, ed. By Demos, Scott and Banerjee (Routledge, 2021), 370.

[13] Ambient Seas, Ravi Agarwal’s diary, 2013-2015.

[14] Madhanagopal Devendraraj and Pattanaik Sarmistha, “Exploring fishermen’s local knowledge and perceptions in the face of climate change: the case of coastal Tamil Nadu, India,” Apr. 5, 2019.

[15] Phone interview with the artist from Delhi, India, May 3rd, 2021.

[16] Artist’s statement for his 2015 exhibition. This text originates in Agarwal’s diary Ambient Seas.

[17] Augé Marc, Non-Places, Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity, trans. by John Howe, (Verso 1995).

[18] See their website in English: http://pondycan.org

[19] The concept, in a philosophical sense, has been elaborated in Deleuze & Guattari’s introduction to A Thousand Plateaus in which the authors try to understand multiplicity, and point to the different models that have been unable so far to reflect it. Deleuze Gilles & Guattari Felix, A Thousand Plateaus, trans. Brian Massumi (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987).

[20] See in particular Timothy Morton, Ecology without Nature: Rethinking Environmental Aesthetics (Cambridge, MA Harvard University Press, 2007) and Akeel Bilgrami, “Capitalism, Liberalism and the Claims of Historical Necessity,” in Marx, Gandhi and Modernity: Essays presented to Javeed Alam, ed. Akeel Bilgrami (New Delhi: Tulika Books, 2014).

[21] See for example Ghosh Amitav, The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable (Penguin Books, 2016); T. J. Demos, Decolonizing Nature: Contemporary Art and the Politics of Ecology. (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2016); Cioc Marc, The Rhine: An Eco-Biography, 1815–2000 (University of Washington Press, 2002).

[22] The poem that is quoted in the work comes in particular from M.L Thangappa, Love Stands Alone, translations from Tamil Sangam Poetry, ed. AR. Venkatachalapathy (India: Penguin Viking, 2010).

[23] Here I paraphrase Caribbean poet of the decolonisation Edouard Glissant, also very much inspired by Gilles Deleuze, who invented the concept of Poetics of Relation: “Rhizomatic thought is the principle behind what I call the Poetics of Relation, in which each and every identity is extended through a relationship with the Other.” In Glissant Edouard, Poetics of Relation, trans. Wing Betsy (The University of Michigan Press, 1997 [1990]), 11.

[24] Stone Christopher D., “Should Trees Have Standing? Towards Legal Rights for Natural Objects,” Southern California Law Review 45 (1972): 450-501.

[25] Simondon Gilbert, On the Mode of Existence of Technical Objects, trans. Malaspina Cecile and Rogove John (Univocal Publishing, 2016).

[26] See for instance Glissant Edouard, Poetics of Relation, trans. Wing Betsy (The University of Michigan Press, 1997 [1990]).

[27] Bigrami Akeel, “Gandhi the philosopher,” Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 38 (39) (Sep. 27 - Oct. 3, 2003): 4160.