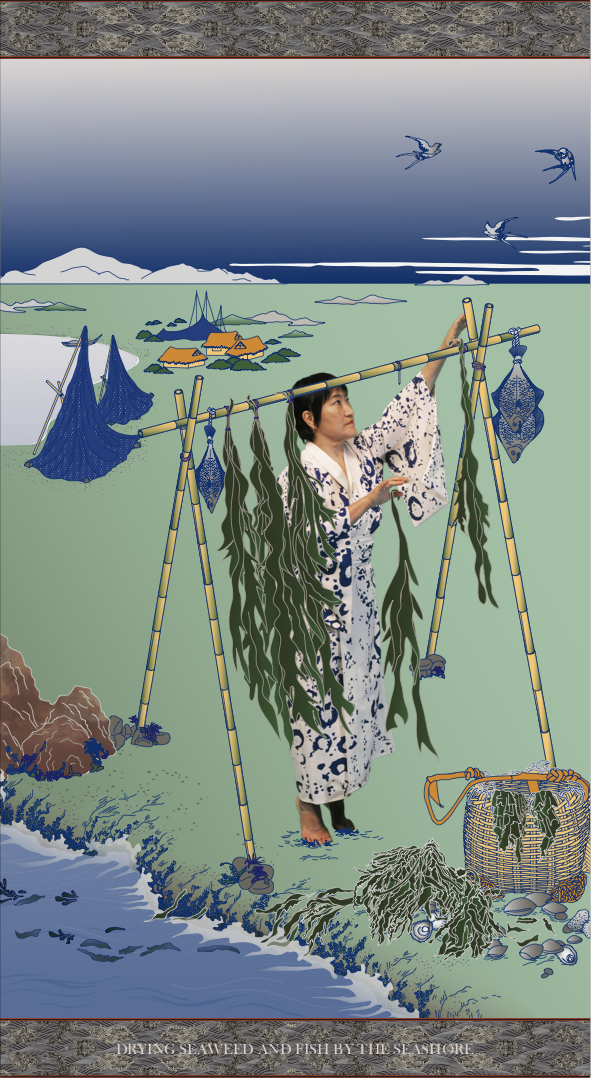

Rodel Tapaya working in his studio. Courtesy of the artist

The Folk Narrative is a series of neo-traditional paintings by Filipino artist Tapaya Rodel. It started in 2007 with the artist’s desire to explore and research local, traditional, folktales and to give them life through an artistic transformation. Drawing from a particular fable, mythological figures, belief or historical event, the artist creates a jungle of hybrid animals, organic webs of plants and objects, interconnected creatures and patches of abstract shapes that unfolds into a complex and dense network of meanings. His large figurative compositions reflect the diversity and multiple layers of the Filipino identity, marked by its colonial history and cultural syncretism. As a reflection of our times, the paintings also offer relevant allegories of today’s society, weaving the past with the present and shedding light on contemporary political, social and ecological issues.

Passionate as he is about the history of the Philippines and about traditional folktales, Rodel Tapaya has been collecting local oral stories and researching how they relate to the pre-Hispanic period of the country. His investigations deal with the influences of the Spanish, American and Japanese cultures on the Filipino traditions as well, and on their expressions in the current society. Despite its richness and variety, the popular folklore had been neglected for a long time. By gathering and critically re-activating these fables, legends and beliefs through his artistic practice, the artist wishes to transmit this heritage while at the same time questioning today’s systems of powers in the country.

Contextual framework and artists’ drive

Reactivating local folktales

Rodel Tapaya, The Land of the Promise (triptych), 2016. First panel. Acrylic on Canvas, 243,8 x 335,3 cm. Courtesy of the artist

Born in 1980 in Montalban, in the Rizal Province of the Philippines, Rodel Tapaya grew up in a large and relatively poor family. His parents were smoking fish for a living and, at the age of eight, his task was to buy some used newspapers and magazines in order to pack the fish. Before handing them to his mother, however, he would look at the lifestyle section, cutting out and collecting images and art reproductions. This was his first exposure to art and he discovered in this way artists such as Anita Magsaysay—Ho, Mauro Malang , Ben Cabrera. These circumstances probably influenced his practice, still very much based on collages and assemblages of anachronical and eclectic elements. Quickly, he began to draw and engaged in an artistic career, pursuing drawing and painting courses at Parsons School of Design in New York, the University of Helsinki in Finland and at the University of the Philippines College of Fine Arts.

From the start, Tapaya has been driven by the rich folklore of his native place, a small town located on the slopes of the Sierra Madre Mountains, famous for its Gorge and for its legendary story: it is said that inside the two facing mountains the national hero Barnardo Carpio is trapped. There are many different versions of this legend, which combines pre-Hispanic elements with Spanish texts and Tagalog folk poems.[1] Fixed in a written form in the 19th century, it has been continuously re-interpreted. The giant hero imprisoned while fighting some villains, or trapped while trying to stop the quarrel between the two mountains, became associated with the national hopes to free the Philippines from the colonizers. During the independence movements, some national rebels went to the mountain to receive his blessing. For Tapaya, the power of such folktales activated his imagination and, as a boy, he would recall investigating on them. These stories were only transmitted orally, and the artist tried to bring them to life by transforming them into colors and forms.

Rodel Tapaya, Ang Huwad na Bernardo Carpio Pagkalipas ng Apat na Siglo, 2006. Acrylic on Burlap 121.92 x 91.44 cm. Courtesy of the artist

The Folk Narrative Series began in 2007, inspired by old local old stories, folktales, legends and myths that the artist had collected from his native region. At first, Tapaya was simply trying to illustrate them, before exploring the multiplicity of their interpretations and connections with the reality. After a time, increasingly, he started combining them, deconstructing and reconstructing their plural meanings and symbolic power while expanding his collection to various other regions of the country. “I like the surrealness and the bigger-than-life quality of the folktales, myths and legends.”[2] For him, the series is still ongoing as he keeps experimenting various ways to approach the contents in a pictorial mode. It is also a way for him to explore Philippine’s pre-Hispanic roots and to reflect on how successive colonizers, from the Spanish to the Japanese, have impacted the local culture and, to some extent, are still modeling some parts of today’s society.

Damania Eugenio, who is known as the “Mother of Philippine Folklore,” notes that it is not before the late 19th century that some traditional folktales began to be collected. However, most of the earliest collections have disappeared, making it urgent to engage in more comprehensive research.[3] By grounding his artworks in history and in Philippine folktales, Tapaya wishes to reactivate them and to emphasize the complexity and the richness of the national culture. “I think teaching history is the best way to know and love your country. And I noticed that we as a Filipino nation we need to work hard to achieve that. I believed the artists can contribute more in this area by creating and telling history, and by showing the beauty and complexity of our culture. In the process, I hope to enliven once again the soul of the country.”[4]

A rich and vivid folklore: syncretism and permeability of influences

Rodel Tapaya, Monkey Beauty, 2013. Acrylic on Canvas, 198 x 136 cm. Courtesy of the artist

Portuguese navigator Ferdinand Magellan first reached the Philippines in 1519 while he was searching for the “Spice Islands” on behalf of the Spanish crown. As soon as he arrived in what is now Cebu, he organized the baptism of around 800 indigenous people, and gave to the queen of the island a wooden carving of the Christ and a Virgin Mary.[5] Rapidly, Catholicism became the dominant religion of the country.

Before the Spanish colonized the territory, the indigenous Filipinos believed in a great creator, or Lord Bathala, who had several ministers interceding with human beings. They were also honoring various spirits and used to perform rituals to please them. Their system of beliefs had no scriptures, and their myths, proverbs, customs, and codes of conduct were handed down orally from past generations.[6] Quickly, though, they accepted Catholicism and assimilated their local spirits with Catholic saints. Consequently, indigenous myths and legends integrated some elements from the Western religion, leading to an original syncretism.[7] Angels were associated with local mythical gods, Christian religious symbols were reappropriated, and cosmologies enriched. They cohabited with ancient supernatural creatures such as the Aswang, a category of dreadful local vampires, viscera sucker, weredogs, witches and ghouls who are still reportedly haunting the country.[8]

All these mythical elements and legends have been reactivated in the end of the 19th century with the rise of local national movements aiming at the independence of the country from the Spanish colonizers. A key figure of the movement was Jose Rizal who was also a pioneer Filipino folklorist and mythologist. [9] In particular, he gave his own version of the story of Bernado Carpio, emphasizing his image of a national liberator. The famous rebels of that time became themselves national heroes, whose stories were integrated in the local folklore as part of the collective memory. For the artist, what is precisely interesting is the blurred border that separates historical facts with myths and legends.

In 1898, the American forces defeated the Spanish, proclaiming military rule and triggering the Philippine-American War. It ended in 1902 with the installation of an American civil government. The Philippines gained its independence in 1946, after a short period under Japanese influence during WWII. While “the American influence resulted in free and universal system of public education, the rule of law, and a court system,”[10] it also brought fast food and elements of the American way of life that remain deeply embedded in the local culture.[11] Retrospectively, some Filipinos described their history as “300 years convent, 50 years Hollywood,”[12] although Tapaya finds this summary far too simplistic. His painting aims precisely at revealing the complexity of these successive yet interwoven layers of influences, which modeled and transformed today’s Filipino identity and traditional collective narratives.

For the artist, folktales allow us to better grasp the past, while, conversely, the past sheds light on the construction of these popular legends. Therefore, he feels it is essential to transmit this knowledge. The task might seem hard to accomplish given the sheer diversity of the Filipino culture, spread across more than 7000 islands and 87 native languages. Yet, Tapaya embraces this variety as he does not attempt to demonstrate any sense of common ground in the Filipino identity.

Corruption, patronage and authoritarian power

Rodel Tapaya, Slave Broker, 2015. Acrylic on Canvas 243,84 x 335,25 cm. Courtesy of the artist

Beyond traditional folktales, the paintings from the series aim to reflect the reality of today’s Filipino society, although always in a metaphorical and allegorical manner, highlighting in particular its post-colonial heritage, political dysfunctioning, blatant social inequalities and ecological degradations.

According to Tapaya, the Spanish colonizers perpetuated a feudal system based on Haciendas (landed estates, originally plantations) that is still at the origin of a current mindset among Filipinos, who tend to feel infantilized and dependent from the government rather than seeking their own emancipation. Besides, this system of patronage, linked to corruption, has led to growing inequalities, increased poverty and economic backwardness. “While the Philippines enjoyed a two-party democratic system, patronage prevented the removal of corrupt or ineffectual officers, and the Congress populated by mostly landowning families often delayed passing important land reform legislation. Towards the end of the 1960s, while many of the country’s neighbors were industrializing rapidly, economic growth in the Philippines slowed down, hampered by import substitution policies favored by the elites.”[13] At independence and during the 1950s, the Philippines was one of the most advanced countries in Asia. However, in 2016, 90% of the Filipinos were classified as lower or working class, of which 27.9% lived below the poverty line. “Despite the economic gains in the last few years, the poverty situation remained dire. (…) Around thirty-three percent of children under the age of five had stunted growth due to malnutrition”[14]

The years following independence did not see the establishment of a real democracy, and the recent decades have been paved with authoritarian governments favoring the elites, bureaucrats and businessmen with the support of the military power. From Ferdinand Marcos’s martial law to the assassination of Benigno S. Aquino Jr, his opponent,[15] and the elections of Rodrigo Duterte in 2016, for whom the laws on human rights are useless,[16] the country has been through chaotic decades that Tapaya aptly represents through his carnivalesque paintings. For him, fear is everywhere under today’s social and political conditions. Since the election of Duterte, an official war on drugs has notably increased extra-judicial killings. During his first year in power alone, it is believed that as much as 12,000 people have been killed without anyone being judged for these assassinations.[17] At the same time, the cronies support illegal logging practices and mining concessions that are leading to a dramatic deforestation of the country, threatening both the environment and the local communities. [18] Nature is pervasive in Tapaya’s artworks, polluted and damaged by human activities, yet the lush jungle seems always to prevail: for the artist, nature will outlive human activities and decadence.

The artist-researcher

Collecting folktales and all kind of stories

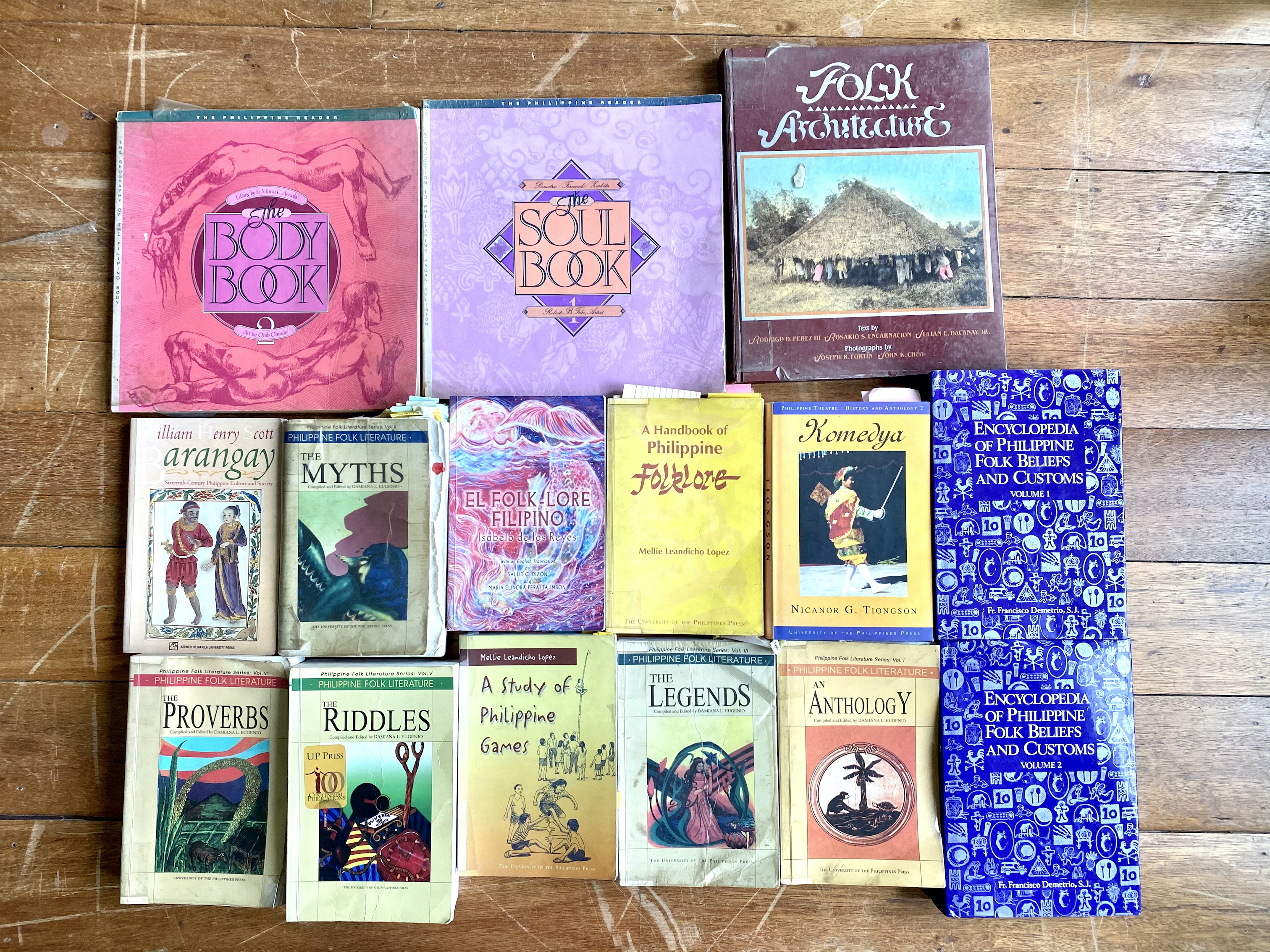

Books from the artist’s collection. Courtesy of the artist

“I try my best to look into different sources of inspiration. I enjoy learning about Filipino culture, stories, history… I try to explore different genres and to find connections with the work or theme I am trying to develop.”[19]

Tapaya defines his practice as mostly research-based, as he has been collecting and investigating pre-Hispanic tales and local stories for many years. His sources are very diverse as he searches for legends but also for ancient proverbs, riddles, games and theater. Most of his research is literary based, although he has been collecting oral stories from old people, especially from Northern Luzon where he lives,[20] and from Visayas (central part of the Philippines) where his parents originate. His fieldwork is always informal, and he is not collecting these stories in a systematic or scholarly methodology. On his way to a province, he talks to the local people and asks them about their childhood memories.

The scope of Tapaya’s investigation is very wide. One of his main references is the work of ethnologist Damiana Eugenio ( 1921 – 2014), a Filipino female author and professor who spent her life studying and compiling Philippine folklore. She classified folktales according to a few categories: animal tales or fables, tales of magic, novelistic, humorous, religious and didactic tales. Although she published many books on the topic, she emphasized the urgency to gather in a more systematic way all the oral stories from every part of the Philippines. She also underlined the lack of interpretation of these tales and proposed a few comparisons with tales from abroad, noting for instance how the story of Cinderella had been Filipinized, since the meeting with the prince happens in a church and not in a ball. Another taxonomy is proposed by Mellie Leandicho Lopez in A Handbook of Philippine Folklore, that provides theories about Filipino folklore.[21] Francisco Demetrio’s Dictionary of Philippine Folk Beliefs and Customs is another important source. Demetrio is the director of the Philippine Folklife and Folklore Center at the Xavier University Museum in Cagayan de Oro in the Southern Philippines, a place that Tapaya visited. The dictionary is arranged in chapters related to themes such as animals, Aswang or Witches, Death, Feats and Celebrations. Demetrios has also written Myths and Symbols in Philippines,[22] describing for example early Filipino myths and studying their evolution but also connecting religious, myths, and oral traditions, a correlation that is also at the core of Tapaya’s approach.

Not only books but TV shows shed light on popular stories. "Lola Basyang" (Grandmother Basyang) is a famous bedtime series that is part of the artist’s childhood in the late 1980s and 1990s. Basyang is actually a pen name of Severino Reyes, a Filipino writer who created and published short traditional stories for children published in magazines and comic books from the mid 1920s. Watching the show gave Tapaya the idea to ask around him about local tales. He painted the figure of the old lady in Grandmother's Tale (2021), showing an almost dying grandmother, perhaps to suggest that storytelling as an art form to relay stories was in the verge of extinction.

Anthropology and history

Beyond and through these oral stories, Tapaya is investigating the pre-Hispanic period of the Philippines history, as well as its colonial era. The artist has always been driven by historical studies, his favorite subject at school. There is no specific Filipino historian that influenced him, but he is following the work of contemporary public historian Ambeth Ocampo through his newspaper column. He especially likes his different approaches of telling Filipino history in a not intimidating way.

Some national heroes such as José Rizal have contributed to the knowledge of the local folklore, in particular with his second novel, El Filibusterismo, published in 1891. The lives and legends of national heroes are part of a collective memory that Tapaya tries to trace back. For instance, he has investigated the life of Macario Sacay, another national hero of the independence who was hanged by the Americans in 1907 and who was remembered as a bandit, after the American propaganda demonized his image.[23]

The study of local riddles, proverbs and games requires an anthropological approach as well. Some of the folktales are also performed, combining theatral art forms with storytelling. Delving into 16th century Philippines, “Barangay” written by American historian William Henry Scott who spent his life in the Philippines, aims at describing how the Spanish colonizers perceived the country when they arrived, bringing forth a rich anthropological perspective on that time. Closer to the contemporary context, Tapaya is inspired by the work of Filipino anthropologist Felipe Landa Jocano (1930 – 2013), a pioneer in the use of Participant Observation as a research methodology in Philippine ethnographic research. He is known for his fieldwork and especially by his book “Slum as a way of life,”[24] in which the artist drew inspiration from for his recent series entitled Scrap paintings.[25] Besides the reference to his own childhood spent in a slum, Tapaya probably borrows the anthropologist’s humanist approach when it comes to portray the urban poor communities.[26] Jocano also documented some local folktales and epic poems. Some of these books are not very popular and Tapaya found them from secondhand sources.

More generally, Tapaya has been influenced by French anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss, historian Yuval Noah Harari and by “magical realist” writers such as Garcia Marquez. Art critic David Elliott notes how the artist had to “learn to compress a whole book within the scope of a group of interlinked images, joined together within a single pictorial plane.”[27] Rather than narrowing his vision, these readings and research practices made his “imagination explodes with images.”[28]

Artistic transformations of the research findings

A storyteller

Rodel Tapaya, The Chocolate Ruins, 2013. Acrylic on Canvas, 304,8 x 731,52 cm. Courtesy of the artist

Tapaya defines himself as a storyteller and his paintings tell stories of their own, an interwoven combination of the artist’s research material with his own imaginative power.

He usually works with very large formats – some of the paintings from the series are more than 7 meters long - for viewers to feel part of the work. This format allows him to concentrate on many tiny details and to play with the contrast between the micro and the macro perspectives of the composition. As a student, and in order to make money, he used to paint houses designed by interior designers, which gave him a good experience of creating trompe-l’oeil and of working on large murals. This monumental format also refers to a long tradition of muralist painters who influence his practice, such as Filipino artists Juan Luna and Carlos Modesto "Botong" Villaluz Francisco known for their historical compositions, and Mexican artists like Diego Rivera and Jose Clemente Orozco. The strong narrative dimension of their works, embedded in social realism, was particularly important for Tapaya who has always favored figurative painting.

In Tapaya’s artworks, many fables and stories co-habit and mingle. His compositions resemble a jungle, a dense entanglement of people, mythical creatures and natural elements. No space is left empty. For the artist, this density and complexity reflect the diversity of the Philippines, the overlapping of various traditions, dialects, groups of people and cultures. The accumulation of overwhelming details echoes as well the Filipino sensibility of horror vacuii or fear of void. In most paintings, the artist’s palette is very bright because the colors originate from his collages and glossy magazines. Tapaya likes to play with the contrast between this joyful aesthetics and the darkness of some of the featured topics.

Rodel Tapaya, Multi-Petalled Beauty, 2012. Acrylic on Canvas 244 x 426.72 cm. Courtesy of the artist

In folktales, animals are often playing the role of human beings, standing for specific human qualities or symbols. A fantastic bestiary supports also Tapaya’s narratives and allegories, with recurring animals and themes. The animal trickster is usually a monkey, but the ape also parodies human beings and their desires. In Multi-Petalled Beauty (2012), for example, a monkey perched on an uncanny plant is transformed into a human being in a quest for beauty and eternal youth. His skin opens like a banana while a pale face of a man emerges, more dead than alive. On his side, a sheep herd is watching him with indifference, except one who stares at us with a lymphatic look. These sheep refer to Dolly and today’s research on cloning. The crocodile, on the lower part, represents the dark intentions of those who take advantage of the new technology, creating fake medicine in order to deceive people. In other works, pigs, crocodiles and frogs embody greed and power while the motif of the skull refers to the afterlife, underworld and death. Manau, the mythological bird of the Philippines, who released the first man and woman from a bamboo stick, is also present in many forms, for example making chocolate in Chocolate Ruins (2018).

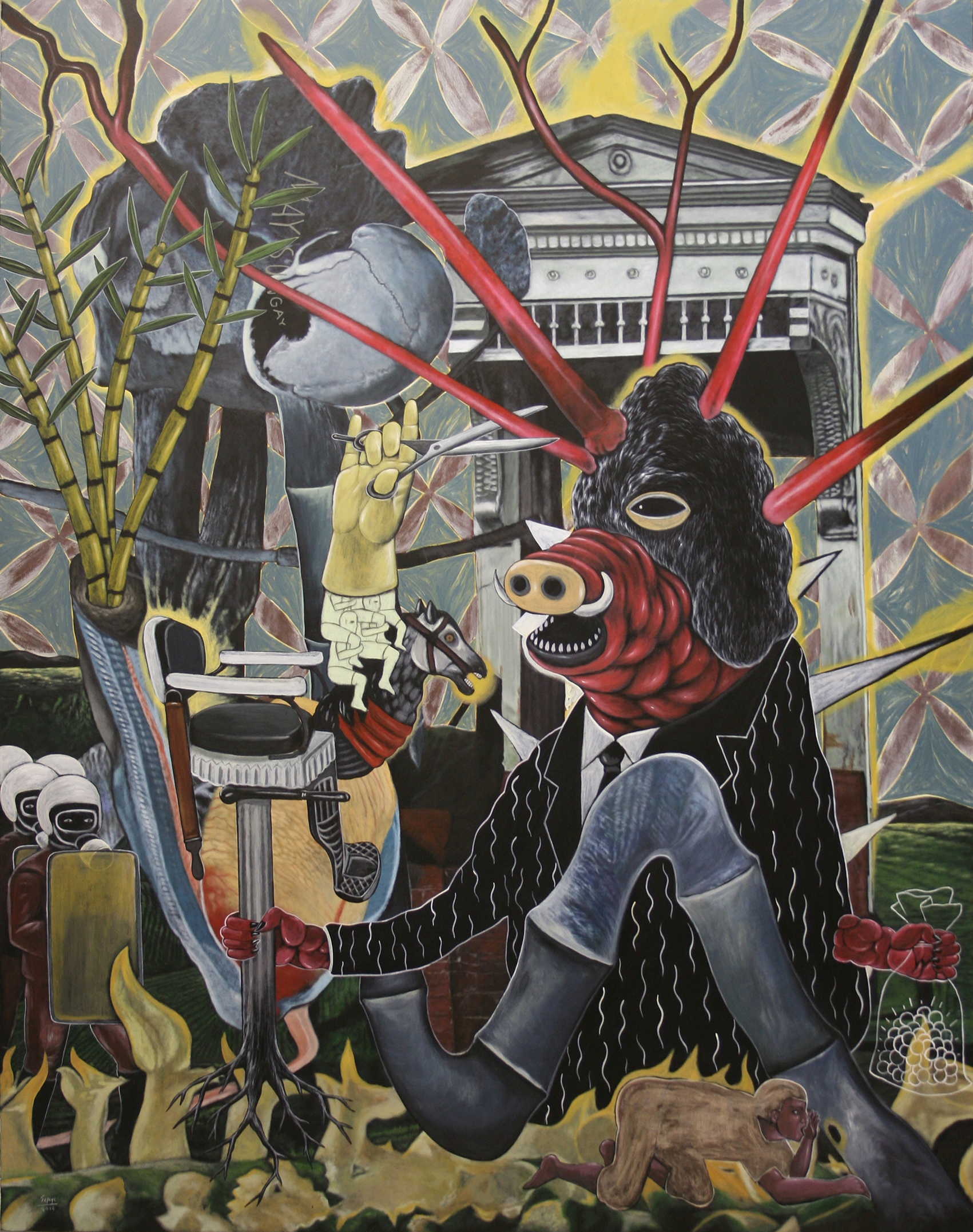

Tapaya uses architectural details and references as another way to put his stories back into specific contexts. A hybrid building with a classical frontispiece stands for instance at the backdrop of Whisper Cutler (2014), in which a horrifying boar wearing a necktie seems to spread terror. For the artist, this white building strengthens the feeling of power and alludes to the seat of governance, imbued with Western influences. In Nang Wala Pang (2010) he painted a traditional house known as nipa house, a typical architecture from a particular tribe in Northern Philippines, in order to root his tale into this region, where it originally comes from.

Rodel Tapaya, Whisper Cutler, 2014. Acrylic on Canvas, 193,04 x 152,4 cm. Courtesy of the artist

Despite these precise references, Tapaya does not wish to restrict his artworks to a Filipino audience. Beyond some national specificities, many myths and stories from various origins are similar and his motifs are clear enough to speak to everyone. He willingly cites Georges Orwell’s “Animal farm” as another possible source of metaphors. As human beings, he also feels that from the beginning of mankind and from the age of our ancestors, we share some similar approaches to the environment and to the world around us.

Organic processes and collages

A story, a piece of news or merely a form can be the starting point of a painting. From one given element, Tapaya will connect his research material with his imagination, letting visual images grow. His process of painting can be very slow as he marks some pauses before completing a work. Working on many compositions at the same time creates some dynamism and gives his imagination the time to unfold.

Since 2011, the artist’s creative process always starts with a collage. Before, the artist only made sketches and images based on his memory and imagination, transferring his studies into larger canvas for painting. However, he felt limited by this process and decided to include collages in order to expand his palette of motifs and colors, adding unexpected elements to his compositions. This practice also offers fertile contrasts between the flatness of the graphic design patterns and more figurative or realist elements, aptly embodying the confusion, and sometimes slippage between myths and reality. “It was like creating a hybrid form of realism, which I think parallels the nature of mythology and myth making, and making sense of stories in the present times. Sometimes, myths are closer to the truth, and facts look more fictional.”[29]

Rodel Tapaya, The Magic Frog, 2014. Acrylic on Canvas, 233,68 x 355,28 cm. Courtesy of the artist

Collages provide a preliminary backdrop for the painting, which might at first remain chaotic. The original collage is scanned and printed, so that Tapaya can draw on top of it, adding more layers of shapes and meaning. “The process is organic, I let the images and forms tell me what to do. I use mind mapping to get my thoughts down and, from a core idea, other ideas branch out and expand. Ideas are like plants that germinate from small ideas to larger ideas.”[30] Through a long process of construction and deconstruction, the artist finds his way in this chaotic ensemble, connecting progressively images, colors and shapes and ordering all the elements. This organic flow and multiple stages of transformations are almost literally expressed in many paintings where forms are growing and expanding like plants, whatever their nature is: arms extend, necks bend unreasonably, thorns can grow from animals’ heads, roots stem from objects and branches from various living species, including abstract shapes, intermingle.

As a result, many eclectic figures and various patterns cohabit in Tapaya’s works, originating in diverse spatial and temporal spheres. This principle of assemblage, or collage, gives a unity to what might hitherto be perceived as antagonist: mythical creatures are juxtaposed to real figures, ghosts from the past are mixed up with contemporary events and animals, objects and human beings are suddenly found side by side. With the accumulation of layers, some motifs literally fly against the background or simply seem to pop up from nowhere. A feeling of the absurd emanates from these original compositions, yet new meanings and narratives arise.

Rodel Tapaya, Instant Gratification, 2018. Acrylic on Canvas, 243,84 x 335,28 cm. Courtesy of the artist

Instant Gratification (2018), for instance, features a giant monkey dressed in a white suit in the setting of a fancy jungle. His left arm is excessively long and holds a bunch of bananas carried by a small turtle. At his feet, a group of ghostly people queue in front of a tiny house, probably eager to buy a lottery ticket. A slot machine is drawn on the side, of almost the same size as the house. From there, abstract shapes grow up and down, following a triangular motif. All the outlines of these elements are very neat and remain oddly autonomous yet their colors match perfectly the background: they seem thus at the same time to be alien to the landscape and to belong to it. On the left, Tapaya plays with successive layers of foliage and leaves in order to create a feeling of depth, although he is using unconventional rules of perspective. Everything looks thus awkward and farcical, with unidentifiable patches of colors and shapes juxtaposed on the top of each other. This static mode of assemblage strengthens the irrational dimension of the painting already given by all its featured surrealist components: tree trunks have eyes, the head of the monkey expands, transparent diamonds float by while busy monkeys are collecting disproportionate shrubs, closely monitored by a second tiny turtle.

This painting was inspired by Jose Rizal’s rendering of a traditional Filipino tale entitled “Ang Pagong at ang Matsing” (The Turtle and the Monkey), a very popular story in which the monkey plays tricks to a turtle who finally revenges. The mortar and pestle, lying on the table, refers for instance to the way the monkey proposes to punish the turtle.[31] Here, Tapaya has embedded the tale in the contemporary society, pointing to the greed and individualism of hi compatriots. The little ghostly people, wrapped in long and black robes, might represent the larger part of the population, roaming around in a quest for money or goods. They can be found in other Tapaya’s paintings as recurrent figures.

Rodel Tapaya, The Sacrificial Lamb, 2015. Acrylic on Canvas, 244 x 335,28 cm. Courtesy of the artist

The process of collage allows the artist to play with these symbolic yet figurative elements. It also aptly expresses the syncretism of Filipino’s identity. Elements from the Tagalog culture are for instance constantly mixed up with Catholic iconography or symbols, reflecting on the complex layers of the history that has shaped today’s Philippines. The Sacrificial Lamb (2015) tells the story of two brothers who sacrificed their beloved sister in the hope to have edible food growing from their garden. For the artist, the story is morbid, but it is very powerful as an act of love. It connects the Catholic religion, in which Jesus gives his life for humanity, with traditional Filipino beliefs. The painting features the two brothers in their garden nearby their traditional houses under a rain of blood. They are engaged in a kaingin or typical technique of cultivation in the Philippines that involves slashing and burning trees for clearing the land. At the back, in a remote and dark mountain, the artist has represented the Golgotha hill with three crosses. The influence of Catholicism is also prevalent in the artist’s representations of the human skull, another recurrent motif, and of the lamb. Titles such as The promised land: the moon, the sun, the stars (2016) connects directly to the Bible. Tapaya plays also on the format of his paintings to highlight the originality of the Filipino culture that embraces many forms of beliefs. The canvas of Monkey Beauty (2013), for instance, is shaped according to a water drop. It refers to traditional amulets which are supposed to bring luck to those who wear them. For the frame, the artist collaborated with local artisans who usually design altarpieces for churches, using brass and tin sheet. Therefore, the painting, by its mere format, blurs the distinction between the different faiths and beliefs.

Contemporary allegories and metamorphosis

Rodel Tapaya, Aswang Enters the City, 2018. Acrylic on Canvas, 243,84 x 426,72 cm. Courtesy of the artist

The chaotic and absurd ensemble of disparate motifs originating in the collage process is counter balanced by a great feeling of interconnectedness between everything: time, places, historical events and myths co-exist and generate each other through successive metamorphoses. More than syncretism, this chosen perspective underlines how the past informs the present and how the present sheds light on the past.

This process of transformation is particularly blatant in Aswang Enters the City (2018) which depicts the invasion of a town by hybrid creatures known in the Filipino folklore as aswang. These mythical beasts resemble pigs with disproportionated tongues. They are a kind of vampires or “viscera suckers,” spreading fear and chaos everywhere while devouring anything they can. In the morning, though, they transform into ordinary human beings. On the left side of the painting, one metamorphosis is under way, with the outline of a pig head arising from the face of a policeman. Meanwhile, the gigantic aswangs are beheading animals and opening their flesh despite some white birds, whose heads have been cut and replaced by human faces, carrying garlic to kill them. In popular thinking, garlic is indeed an antidote used against these supranatural creatures. The bloody scene, which is rooted in very old beliefs, refers to the contemporary extra judicial killings that happen often at night in the country, spreading equally fear and terror. It hints at president Duterte call when he declared in 2016 “Please feel free to call us, the police, or do it yourself if you have the gun — you have my support. Shoot [the drug dealer] and I’ll give you a medal.”[32] Policemen are turning into criminals while normal citizens can thus legitimately claim they become policemen in a frightening game of transformations.

In the lower part of the artwork, a hooded man is pointing to a direction, as if he had identified a target. His mask, a woven basket made from dried leaves, is a typical mode of representation of an armed group known as makapili, a term meaning “to choose” since its members used to identify who they wanted to kill. The group was founded during the Japanese occupation of the Philippines in 1944 with the aim to serve the Japanese army and spy the local population. They call themselves Alliance of Philippine Patriots although they were not patriots but traitors. After the war, the group did not disband and continued to wield their power with terror. The hooded man is the central figure of another painting entitled Hooded Witness (2019). He is holding binoculars and one can only see his eyes as the basket protects his identity. On the upper part of the artwork, a monstrous policeman in uniform is represented. His head is that of a ferocious dog and he is holding some dead rats in his hand. The color of his skin is green and instead of hands, his right arm extends into two gnarled snakes with big bulging eyes. For Tapaya, these people are “like dogs hunting for rats. They are reducing other people to pests, creating collateral damages and leaving widows and orphans in the so-called battlefield of war behind.”[33]

Rodel Tapaya, The Hooded Witness, 2019. Acrylic on Canvas, 152,4 x 121,92 cm. Courtesy of the artist

The present seems here to unfold in continuity of the past. This interdependence is also clear in all the paintings referring to the colonial times, such as The Chocolate Ruins (2018) in which the artist suggests that the feudal systems inherited from the colonial powers are still shaping today’s Filipino society. In this very large painting, the mythological bird of the creation is pouring cocoa beans into a processor, yet its production vanishes into a dense jungle of objects and absurd creatures. Behind him, a large yellow cocoa flower gives birth to a long snake whose body disappears into a chaotic landscape. Besides figuratively embodying the typical colonial product, cocoa is here associated with corruption and the unbalanced systems of power inherited from the Spanish.

Finally, the organic process of metamorphosis and the general interconnection between human beings, living creatures and objects reflects the artist’s concern for ecological issues. In Manama Abode (2013), for example, the body of a man is emerging directly from the rock. One of his arms gives birth to a bird while his third hand is still petrified in the mountain. Manama is the name of a mythical god in the Manobo tribe in the southern part of the Philippines. In this painting, the power of nature is underlined with a giant and magnificent flower arising from the center of the composition. The myths and fables that Tapaya refers to talk about pre-human worlds whose forces overcome human activities. However, and often introduced in smaller details or as a background, one can find hints at the human impact on nature despite the interdependence that connects every living creature. In Chocolate Ruins (2018), for instance, the scene takes place in Chocolate Hill in the Bohol province of the Philippines, where a deadly earthquake happened in 2013. While the hill collapses, with poor people looking for shelters, the giant bird continues to make his profitable chocolate.

Conclusion

Rodel Tapaya, Manama’s Abode, 2013. Acrylic on Canvas, 193 x 152,5 cm. Courtesy of the artist

With the Folk Narrative series, Rodel Tapaya combines and converts ancient oral folktales from the Philippines into artistic forms and gives them a contemporary twist. His research engagement allows him to collect and gather a great diversity of these fables and stories, contributing to their re-activation. The narration is aptly supported by the large-scale format of the paintings, their bright colors and often impressive motifs, although the artworks are dense and complex.

This research-based and artistic practice allows Filipino people to remember their own traditions, and foreigners to discover them. However, this re-activation and transmission can be ambiguous. Fragmented, re-interpreted and recomposed through successive metamorphoses, the original stories might indeed disappear, overlapped by the artist’s own narration. Tapaya is using the language of the tales and the ready-made language of the media in order to express his feelings and to comment on the reality of today’s Filipino society. By doing so, he perpetuates the tradition which consists of recontextualizing and re-interpreting these folktales in light of the contemporary period, just like José Rizal did when he used the fables during the independence movement. Nevertheless, some parts might be lost during this conversion. Besides, the artist converts an oral tradition into visual forms, perhaps contributing to the erosion of the culture of orality, which hitherto characterized these popular stories.

That being said, Tapaya demonstrates the power of the symbolic and narrative vocabulary of folktales which seem still relevant to reflect on contemporary issues. His figures unfold with an incredibly expressive force that transcends every cultural framework. The next step could be, perhaps, to move away from collages and existing visual references in order to invent a new narrative language and a new grammar of forms that could translate the vigor of the Filipino rich oral traditions in a totally renewed and creative manner.

[1] See for instance Scalice Joseph, “Pamitinan and Tapusi: Using the Carpio legend to reconstruct lower-class consciousness in the late Spanish Philippines,” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 49(2) (June 2018): 250–276.

[2] Email conversation with the artist, August 25, 2021.

[3] For the scholar, “there is a need to compile, edit, and publish anthologies, regional and national in scope, in order to make these folktales known and available to the people.” See Eugenio Damiana, “Philippine Folktales: An Introduction,” Asian Folklore Studies Vol. 44, No. 2 (1985): 155-177.

[4] Email conversation with the artist, April 19, 2021.

[5] Castillo del Fides A., “Christianization of the Philippines,” Mission Studies 32 (2015) 47-65.

[6] Castillo del Fides A., “Christianization of the Philippines,” Mission Studies 32 (2015), 52.

[7] See for example the Pasyón (Spanish: Pasión), a Philippine epic narrative of the life of Jesus Christ, focused on his Passion, Death, and Resurrection and told through an original form of epic poetry.

[8] See in particular Ramos Maximo, "The Aswang Syncrasy in Philippine Folklore" Western Folklore 28 (4) (Oct. 1969): 238–248.

[9] Demetrios Francisco, The Religious Dimension of Some Philippine Folktales,” Asian Folklore Studies Vol. 28, No. 1 (1969): 51-76.

[10] Lau Dawn H. and Rithmire Dmeg, “Philippines: From Sick Man to Strong Man,” Harvard Business School n°9 (June 13, 2017): 2.

[11] Friend Theodore, “Philippines-American Tensions in History,” in Crisis in the Philippines, ed. John Bresnan, (Princeton University Press, 1986), 3-29.

[12] Lau Dawn H. and Rithmire Dmeg, “Philippines: From Sick Man to Strong Man,” Harvard Business School n°9 (June 13, 2017): 2.

[13] Lau Dawn H. and Rithmire Dmeg, “Philippines: From Sick Man to Strong Man,” Harvard Business School n°9 (June 13, 2017): 4.

[14] Lau Dawn H. and Rithmire Dmeg, “Philippines: From Sick Man to Strong Man,” Harvard Business School n°9 (June 13, 2017): 12.

[15] On Marcos presidency, see in particular Garner Noble Lena, “Politics in the Marcos Era,” in Crisis in the Philippines, ed. John Bresnan, (Princeton University Press, 1986), 70-113.

[16] At his final presidential campaign rally, in May 2016, Rodrigo Duterte said “Forget the laws on human rights.”

[17] “In January 2018, Philippine police acknowledged that approximately 4,000 suspected drug users or sellers had been killed in the war on drugs, while Human Rights Watch put the number at 12,000 6 and Philippine human rights advocates claimed it was more than 16,000.” Johnson David and Fernquest Jon, “Governing through Killing: The War on Drugs in the Philippines,” Asian Journal of Law and Society, Vol 5 (2) (Nv. 2018): 359.

[18] Experts predict that the country “will likely be completely denuded by 2025.” Bengwayan A., “Illegal Logging Killing Philippine Forests,” Eurasia Review, June 4, 2019 (https://www.eurasiareview.com/04062019-illegal-logging-killing-philippine-forests-oped/)

[19] Email conversation with the artist, August 25, 2021.

[20] Tapaya lives and works now in Bulacan, a province located in Central Luzon.

[21] Lopez Mellie Leandicho, A Handbook of Philippine Folklore (Quezon City : University of the Philippines Press, 2006).

[22] Demetrios Francisco, Myths and Symbols Philippines (Manila: Navotas Press, 1978).

[23] More of this national figure, see for instance Cinco Maricar, “Camp's name change is first step to correct history,” Philippine Daily Inquirer, 2 Dec. 2016.

[24] Jocano Felipe Landa, Slum as a way of life: A Study of Coping Behavior in an Urban Environment (University of the Philippines Press, 1974).

[25] See Ha Thuc Caroline, “Random Numbers,” Artomity magazine (Spring 2021): 54-63.

[26] One of Tapaya’s exhibitions was actually entitled Looban (Slums) at the Boston Gallery in Cubao in 2006.

[27] Elliott David, “The One You Feed. Stories and Images in the Work of Rodel Tapaya” in Matthias Arndt (ed.), Rodel Tapaya, Berlin, Distanz, 2015): 9.

[28] “Rodel Tapaya Mines Filipino Folklore for ‘Ladder to Somewhere,’” Blouin Artinfo South East Asia, April 3, 2013. Cited in Elliott, Ibid. 10.

[29] Email conversation with the artist, August 25, 2021.

[30] Email conversation with the artist, August 25, 2021.

[31] More on this tale, see Eugenio Damiana, “Philippine Folktales: An Introduction,” Asian Folklore Studies Vol. 44, No. 2 (1985): 161.

[32] Kaiman, Jonathan (2016a) “Meet the Nightcrawlers of Manila: A Night on the Front Lines of the Philippines’s War on Drugs,” Los Angeles Times, 26 August. Cited in Johnson David and Fernquest Jon, “Governing through Killing: The War on Drugs in the Philippines,” Asian Journal of Law and Society, Vol 5 (2) (Nv. 2018): 359.

[33] Email conversation with the artist, August 25, 2021.