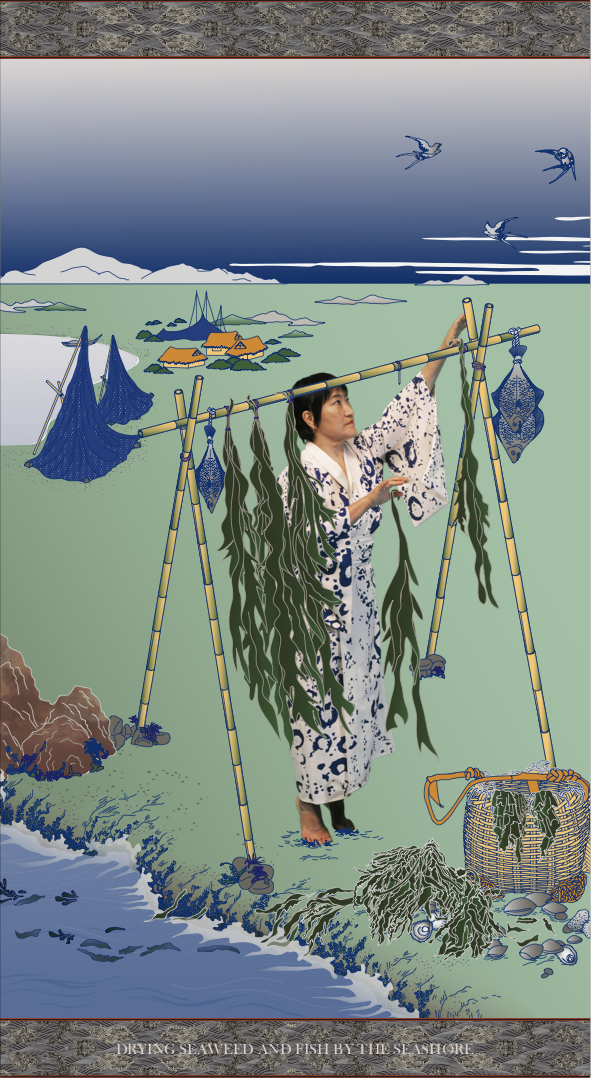

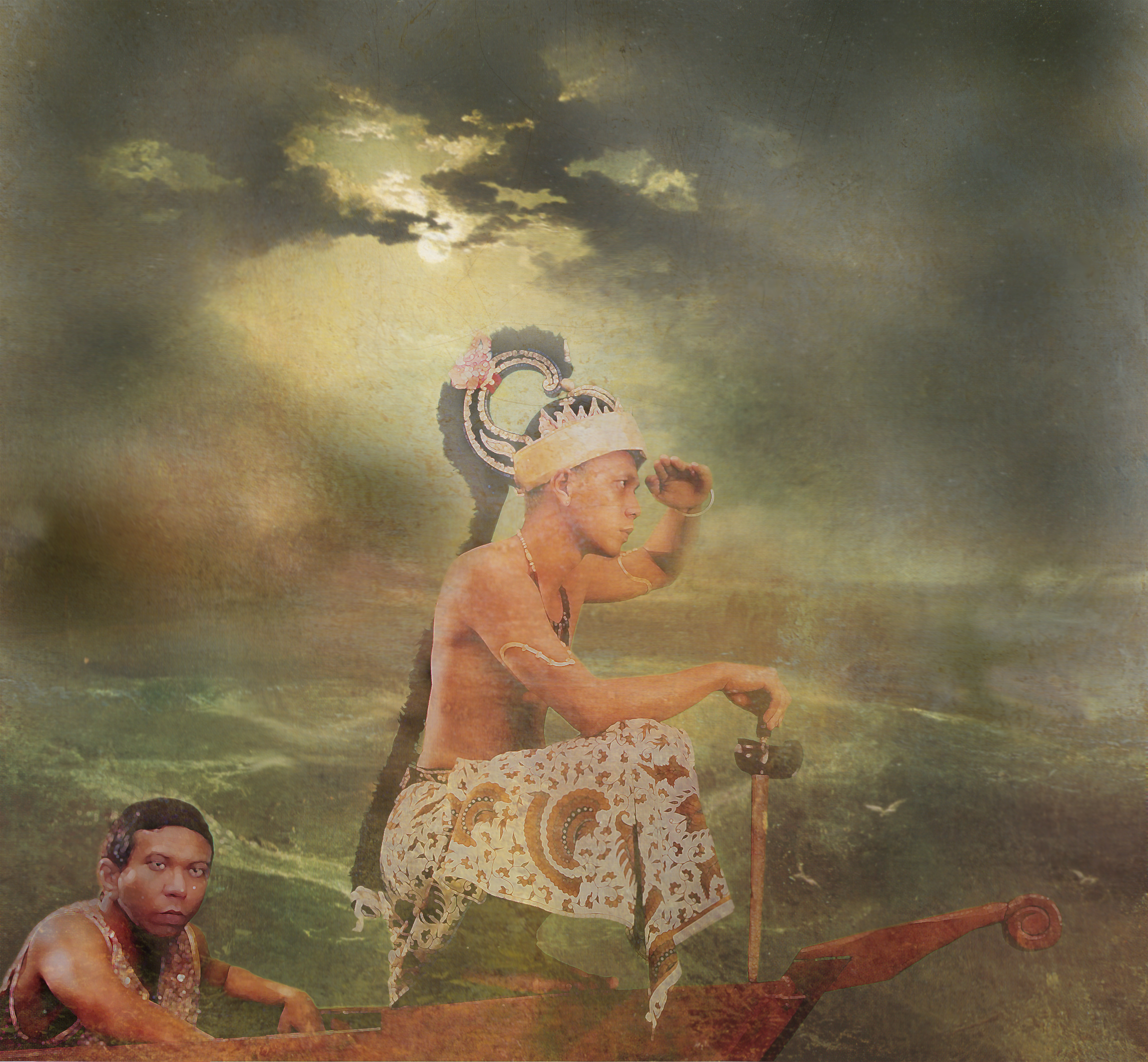

Still image from One or Several Tigers (2017). (tiger sun)

All images courtesy of the artist

One or Several Tiger (2017) is Ho Tzu Nyen’s last piece of a series of artworks dealing with tigers in Southeast Asia. His research began in 2012 and led to the creation of four different artworks revolving around this real yet mythical animal figure: Like The song of the Brokenhearted Tiger (2012), a heavy metal concert featuring a traditional Malay dancer; Ten Thousand Tigers (2014), a theatre performance including shadow puppetry; 2 to 3 Tigers (2015), an animation video; and, finally, One or Several Tiger (2017), a 2 channel video installation that combines many elements of the former works and complete them. Conceived as a duet between a computer-generated tiger and a man, this artwork addresses the ambiguity of tiger-human relationships and explores in particular its symbolic expression in colonial and post-colonial Singapore.

This set of artworks marks also the official point of departure of the artist’s larger and ongoing research on Southeast Asia, a research which he has been developing under the umbrella name of his Critical Dictionary of Southeast Asia. What he calls a “a generator of projects,” or an artistic platform, is an open-ended matrix organized freely around alphabetic letters. It aims at exploring the essence – if any - of Southeast Asia as a regional entity.[1] Since a single artwork could not have been able to reflect on the plurality and complexity of this essence, The Critical Dictionary of Southeast Asia deploys into many and various artforms that often dialogue with each other.[2] Whilst emphasizing the constructed reality of the term, such a process contributes to give it a substance, thus giving visibility to what has always been considered as the periphery of the periphery[3].

As a Singaporean artist, Ho Tzu Nyen (b.1976) lives and works at the core of Southeast Asia. His drive for research originates in his passion for scholarship but derives also from the post-colonial and authoritarian context he is working in. Since his early works, he has explored different modes of visual and sound languages in order to generate artistic forms of knowledge that would challenge at the same time the colonial and the post-colonial binary ways of thinking. His practice rather opens up to a plurality of conceptions of knowledge based on novelty, imagination and emancipation that would embrace rationality and beliefs, traditions and technology, nature and culture, grand narratives and individual memories, centers and peripheries.[4]

Contextual framework and artists’ drive

T for Tiger

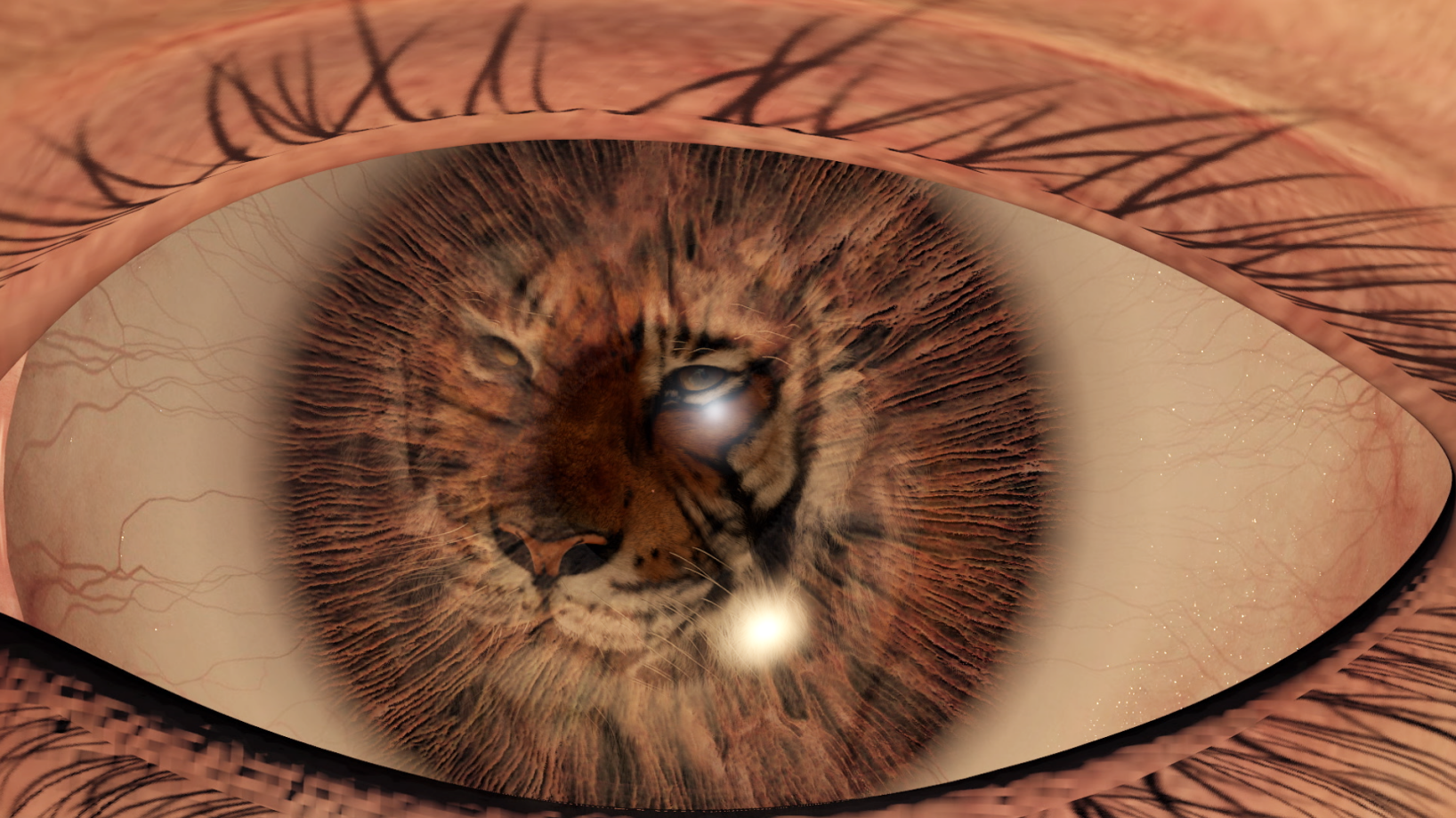

Still image from One or Several Tigers (2017). (iris)

Since Ho works against any form of linearity, it is not surprising that the first letter of his Dictionary was T (rather than A). The main entrance is T for Tiger, in which he mainly examines the history of tigers in Southeast Asia as well as their metaphorical and mythical representations.

Long before the arrival of Homo sapiens in the region, the Malayan Peninsula, Sumatra, Java, Bali and Borneo formed a single land mass called the Sunda Shelf where tigers could jump from one territory to another without crossing any sea. Hence, when the first humans arrived in the region, in about 100,000 years before present, they were prompt to consider these animals as their ancestors and to give them a central role in their cosmology.

In the indigenous culture of the Malay world, tigers embody invisible forces such as ghosts or spirits, and are alternatively considered as friends or enemies. In any case they arouse fears and respect. Often associated with wilderness, they were sometimes deemed as evil but after the colonization of the region they were for instance linked to the mighty Europeans or even to the King’s court.[5] Tigers attack by surprise and always from behind, which adds to their bad reputation. They are also said to be ghoulish and cruel, although most tigers do not eat nor kill human beings because the human smell is repulsive for them. This is why tigers who attack human beings form a special type of tigers called man-eaters.[6] One of the manifestations of tigers is the weretiger, a half-human half-tiger creature that crosses boundaries between life and death or, precisely, between civilization and wilderness. Belief in weretigers in Java is documented from the early nineteenth century onward, but a Chinese source mentions a weretiger in Malacca as early as the early 15th century.[7] One will transform into a tiger, or a tiger into a human being, by crossing a special stream and the water element is strongly associated with such transformations. Shamans and weretigers were often compared and assimilated.

With colonization, and the colonial necessity to expand productivity and arable land, tigers were regarded as a threat and were trapped or killed for a bounty, while their territories of habitat were destroyed. The hunting practices of the colonizers, who wanted to demonstrate their power over wilderness and nature, participated as well to this extinction.[8] In particular, in Java, Dutch colonizers took over a traditional ritual called rampog macan during which tigers were fighting and were publicly executed in the royal courtyard.[9] In Singapore, by the beginning of the twentieth century, they were almost extinct.

T for Theodolite

Heinrich Leutemann Road Surveying Interrupted in Singapore

Wood engraving, 1865

In 1819, led by Thomas Stamford Raffles, the British established a trading port on the territory of Singapore and founded the British crown colony of Singapore. Although tigers were often living at the edge of forests, it seems that the British did not really discover their existence before the 1830s when they started to clear the land and went deeper into the wood in order to create plantations.[10] Between 1825 and 1860, in order to solve labor shortages, the colonizers imported several thousand, mostly male, Indian convicts.[11] Working on the newly cleared lands, these workers were the ones who might meet tigers as they were working at the frontier of the jungle. As more workers were eaten (or died from disease and exhaustion), more workers would arrive by boat to replace them, without any records about the toll to be known. This is what art historian Kevin Chua is referring to when he states that “early colonial Singapore was built on a ghostly labor,”[12] a sentence that has often been incorporated in Ho’s artworks.

For his series pertaining to the history of tigers in the region, Ho’s point of departure is a print he found at the National Gallery of Singapore featuring the encounter of a tiger, Indian convicts and George Drumgoole Coleman, the first Superintendent of Public Works in Singapore. The engraving, Road Surveying Interrupted in Singapore by German artist Heinrich Leutemann,[13] dates from 1865 and depicts a British survey mission from 1835 interrupted by this sudden confrontation: a tiger jumps out of the jungle, provoking the fall and fear of the working team.[14] In the center of the composition, the artist represented a theodolite, a measuring instrument used to build roads, draw maps and fix boundaries. As such, it can be considered as an emblem of colonization based on land clearing, exploitation and control. In the print, the tiger does not seem to attack anybody but to aim at destroying this surveying device.

Still image from One or Several Tigers (2017). (theodolite)

Coleman, who stands as the typical white man, dressed in a white suit, was in charge of public works but was also in charge of prisons: at that time, building roads, cathedrals and prisons were complementary missions since the workers and the prisoners were the same Indian convicts.[15] Singapore was known for having the most advanced prison of that time with a sophisticated system of surveillance and promotion of convicts who tend to watch and denounce their own fellows for rewards. For Chua, the life of these workers who were deprived of political rights were close to an animal life. They embody the crowd of the unknown workers who built Singapore at the price of their life, without never being recognized. In this reading of the work, the tiger is there to create the bridge between them and the animal world. The art historian connects their extinction, and the extinction of other animal species, to the death penalty that is still currently legal in Singapore, and which deprives people from their life in a similar deny of their rights.[16] According to the artist, today, and thus 50 years after British colonization, there are more than 300,000 construction workers in Singapore who continue to contribute to the building of infrastructures and buildings. Mostly originating in Bangladesh, they often live at the margins, are under-paid and do not benefit from any social safety net.[17] While the gaze may focus on the encounter between the tiger and the colonizer in Leutemann’s engraving, Ho wanted to highlight the role of these convicts and to reflect on the power relation they are still trapped in.

Entering the myth

American anthropologist Robert Wessing highlights the symbolic role of tigers in Southeast Asia. According to him, this symbolic power “lies in the ambiguous nature of his relationship with man. This relationship parallels the opposition between men and beasts, civilization and nature, controlled and uncontrolled power.”[18] Tigers are indeed animals of frontiers, they can cross the boundaries between life and death and transform from animal to man. Therefore, and despite their almost total extinction, they survived in the region as myths and metaphors, embodying many heroes or enemies in the more recent history of the region.[19]

Still image from One or Several Tigers (2017). (tiger in cosmos)

In One or Several Tigers, Ho refers in particular to the Japanese General Tomoyuki Yamashita, known as “The Tiger of Malaya.” As the commander of the Japanese 25th Army, he is famous for his successful attacks on Malaya and Singapore during World War II. Like tigers who know how to move fast in the jungle, but who can also be cruel, he and his soldiers invaded swiftly Malaya and obtained the surrender of the huge British naval base in Singapore in 1942. Later, he was sent to the Philippines where the Japanese soldiers, under his command, committed atrocities and violated the laws of war. He was thus condemned after the war for war crimes and sentenced to death by hanging.

During the cold war, communists were also often associated with tigers as they used to hide and mostly remained outlaws. In this specific work, Ho does not include any figure from the Malayan Communist party, but these guerillas fighters play a prominent role in his Dictionary. For the artist, tigers and weretigers embody people or communities who live at the margins of the society and whose lives might be exchanged for a bounty. Yet, according to him, today’s Indian convicts are not like tigers but rather the preys of another dominant economic system that reproduces colonial paradigms.

Hence, with the exploration of the figure of the tiger in the Malayan world, Ho creates surprising parallels and connections within Southeast Asian history, disrupting its usual linear narrative and giving visibility to events or people who had been hitherto neglected. Besides, by emphasizing that there were no lions but tigers in the region, the artist playfully challenges the name of Singapore, known as the “Lion City,” departing from the official Singapore history.

The extinction of tigers following colonization marks as well a rupture in the local culture, with nature being tamed and people cut off from it. “Colonization is not just the conquest of land, not just the formation of disciplined subjects; it is also the war conducted against rival animal populations.”[20] By focusing on weretigers and on the symbiosis that links tigers and men, Ho points to the ecological violence of colonization and to the forms of dualisms it brought forth in the region. Against these Western dual conceptions of the world, the artist emphasizes processes of metamorphosis and interdependence that characterize animism and, beyond, more inclusive, plural but also ambiguous forms of thinking. Ontologically, these passages from one species to another suggests a common essence of beings located outside their bodies, which function thus only as mere envelopes.

The artist researcher

Still image from Utama (2003)

Installation with 20 paintings and single channel SD video, 23 min.

Collection of Fukuoka Asian Art Museum

An academic researcher

For each artistic project, Ho estimates that 70% of his time is dedicated to research. In fact, research and academic knowledge might be what led him to art: as a child, he did not have so much exposure to art forms, and it is through reading that he began to feel attracted by the field, being especially inspired by avant-garde movements and art theories. Originally a student in communication, he quit this path for a BA in Creative Arts in Melbourne. He majored in sculpture, feeling attracted by artists such as Richard Serra, but once he came back to Singapore, he realized that sculpture was not an easy medium to deal with, especially without a studio space. Video, being what he calls “a medium for compression,” appeared as a solution. His video works, as we will see, can actually be perceived as sculptural in their ability to unfold and create multilayered dimensions one could walk into virtually.

Driven by his passion for academic research, reading and writing, Ho then embarked into a master’s degree in Southeast Asian studies with the National University of Singapore, interested in the cross-disciplinary dimension of these studies, from anthropology to art and history. From the beginning, his artworks have been informed by his readings and academic research. His first artwork, a 22-minutes film entitled Utama: Every Name in History is I (2003) is based on his research relative to the history of the Prince Sang Nila Utama, a Srivajayan prince from a South Sumatra province who is said to have founded Singapore in 1299, and of whom he searched the lineage and legacy. Another example of Ho’s previous research-based artwork is The Cloud of Unknowing (2011), exhibited at the 2011 Venice Biennale. Besides its extensive collaborative part involving various musicians, the video originates in the artist’s interest for the iconography of clouds, analyzed through the history of art both in the West and in China. Ho’s study encompassed classical paintings but also poetry and theoretical texts such as books written by the 17th century Italian iconographer Ceasare Ripa or The Theory of the Cloud (2002) by art historian Hubert Damisch.

Still image from The Cloud of Unknowing (2011)

HD projection, 13 channel sound, smoke machines, floodlights, show control system

Collecting data and building diagrams

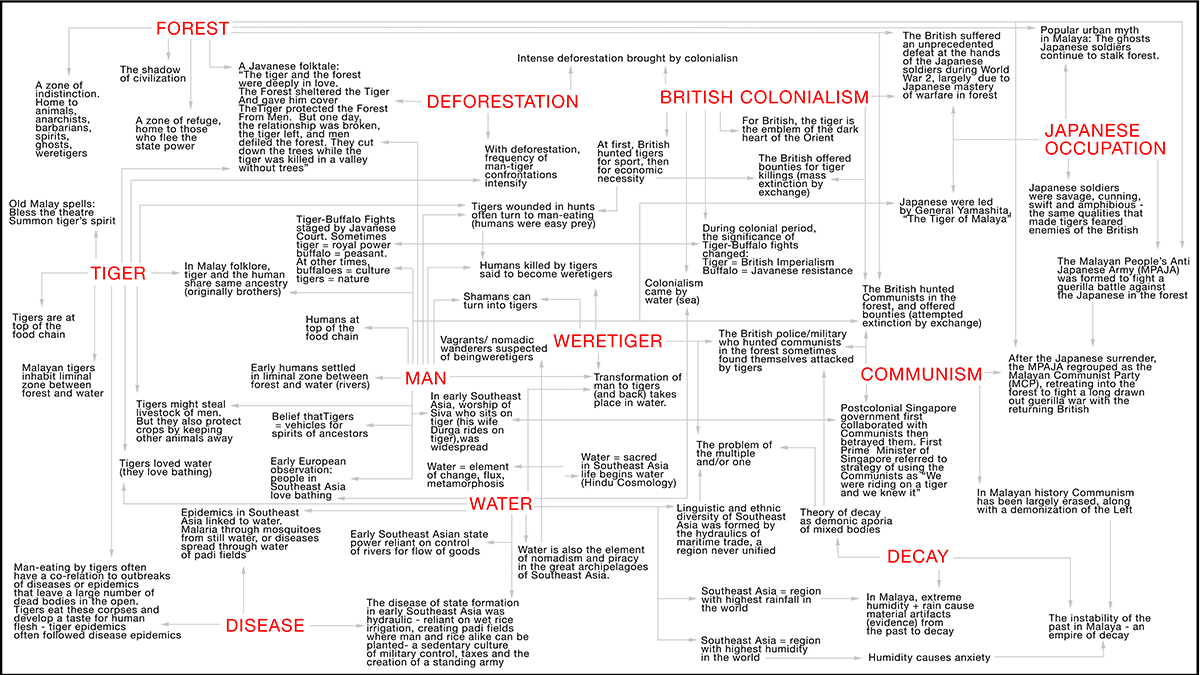

Tigers’ diagram.

Ho has been investigating the relationship between men and tigers in the Malayan world since 2007 and this theme was among the first threads he followed to map, deconstruct and explore the concept of Southeast Asia. Systematically, he read all possible books and articles he could find on the topic, delved into different kinds of archives and academic sources but also searched for documentaries and films. Among the most significant essays that have participated in the shaping of his thoughts about tigers are works by Robert Wessing such as “Symbolic animals in the land between the waters - Markers of place and transition” and “The Last Tiger in East Java: Symbolic Continuity in Ecological Change;”[21] Peter Boomgaard’s 2001 book Frontiers of Fear: Tigers and People in the Malay World, 1600-1950 but also texts about the Japanese occupation of Southeast Asia, about the Malayan Communist Party,[22] and even texts such as To Tame a Tiger, The Singapore Story, a 1995 graphic novel whose cover shows Lee Kuan Yew, the former prime minister of Singapore, riding a tiger.[23] Although many of his sources are anthropological, Ho does not engage in any fieldwork since he believes that “much fieldwork has generated works that are mediocre, or that are lost in clichés.”[24] He however recognizes that the hundreds of hours he spent going through online videos could be regarded as a kind of ethnographic engagement with today’s community.

Ho draws also on more philosophical essays such as George Bataille’s 1949 essay The Accursed Share in which the French philosopher associates tigers with the incandescence and energy of the sun and develops a political theory based on people’s use of their similar excess of energy.[25] More generally, the philosophy of Deleuze and Guattari, whose Anti-Oedipus was the first philosophical book he ever read, left a deep and lasting impact on his work methodology. Later, the reading of A Thousand Plateaus in which the authors try to understand multiplicity and develop their rhizomatic mode of thinking influenced Ho’s approach to knowledge and the open-ended structure of his Dictionary at large, and more particularly of most of his artworks including One or Several Tigers.[26]

Tigers’ atlas

Ho’s research process takes indeed the form of a collection of discourses, images and information that keeps growing and has no end. Some topics led indeed to others, and he follows them like spoors, expanding progressively his field of research. This is how, for instance, his research on tigers led him to explore the left-wing movements from the 1940s in Southeast Asia. In order to organize all this various and exponential amount of data, Ho builds maps and atlases that structure the flow of information and the web of his research findings. They will serve as the base of all his artworks and constantly nourish his inspiration. His video scripts, for instance, resemble essays, including a lot of footnotes and academic references. In designing these diagrams, the artist also processes the various data he collected and converts a large part of his research findings into a form of pictorial knowledge so that they can better resonate with each other.

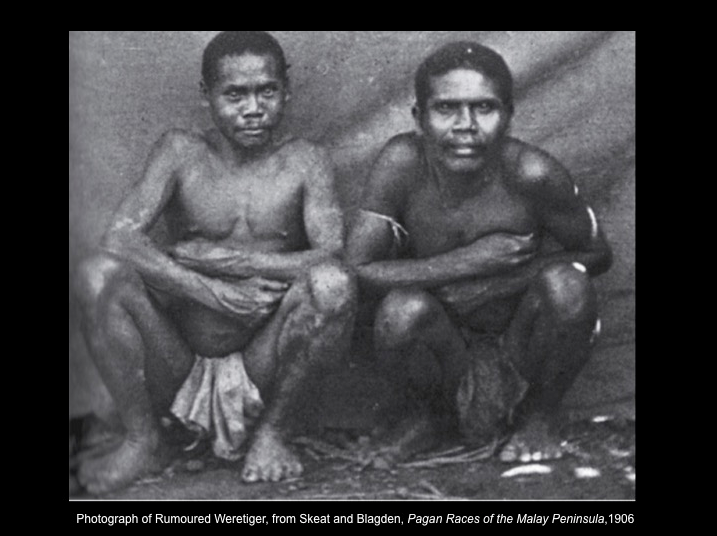

In one of his diagrams, one can see how tigers and weretigers are linked to a complex network of multiple elements and manifestations from Southeast Asia including British colonialism and communism, but also politics of deforestation and water as an element of nomadism, change and flux. Each entry is described and developed from a historical, economic, social, cultural or geographical perspective. This discursive diagram is paired with an atlas where the artist has assembled a series of images pertaining to the tigers, similarly all connected and described by short subtitles such as “Buffalo-tiger fights”, “BRITISH RETURN, The Malayan Communists retreat into the Forest (becoming tigers),” “shadow puppetry,” or “Japanese occupation.” Many of these images are then included in his artworks. In particular, Ho found back a black and white image from 1906 taken by Walter William Skeat, a British anthropologist who allegedly was the first photograph who captured the image of weretigers.[27] In this image, two squatting Malays are staring at the camera as if their gaze was fixed. The caption says they were weretigers, but it is impossible to guess who they are from the photograph, although this kind of look is often perceived as a manifestation of a singularity.

In the theatre performance Ten Thousand Tigers (2014), two actors were reproducing the attitude of these natives. The photograph features as well in One or Several Tigers, with the voice-over explaining its origin. Some of the artist’s sources are indeed indirectly quoted in the discursive part of the video (subtitles and/or voice-over), but most of the time Ho does not refer to them. Some sentences of the video are for instance extracted from Peter Boomgaard’s 2001 book Frontiers of Fear: Tigers and People in the Malay World, 1600-1950, yet there are no quotation marks, and it is impossible to distinguish between the artist’s own text and his citations. These extracts rather function like the images he uses, that is as fragmented elements that he assembles freely to create his multimedia collages. The artist does not display these documentations either,[28] but mentions them during talks or interviews. Therefore, while he borrows his research methodologies from the academic field, Ho emancipates himself from its canonical rules and plays at will with his references. In 2007, the artist nevertheless wrote an academic essay pertaining to the history of tigers in Singapore and Southeast Asia, which might have served as a base from which he later developed more freely his creative pieces. [29] In fact, most of his works could be perceived as different experiences aiming at converting the outcome of his research into artistic, and often more sensory, languages.

Walter William Skeat, photograph of weretigers, Pagan Races of the Malay Peninsula, 1906.

Ultimately, Ho’s research process does not directly aim at filling any particular knowledge gaps but rather at creating original connections between elements that are usually studied separately. This cross-disciplinary approach allows him to propose renewed perspectives on established narratives. Nicolas Bourriaud’s concept of Post-production and his image of the artist working as a DJ come immediately to mind because Ho seems to recycle existing material and to re-appropriate it in his own way. [30] “I am not cool enough to be a DJ” said Ho, yet his assemblages of multiple and heterogeneous elements, which he rather calls manifestations of Southeast Asia, could be seen as a way to deejay: creating new vibrations and sounds from existing data, including noise and beats. Like the artists working in post-production, his work involves an “incessant navigation within the meanderings of cultural history” and, as far as he is concerned, also within the labyrinth of political history that form “new cartographies of knowledge.”[31]

Artistic transformations of the research findings

A non-linear and fragmented narrative

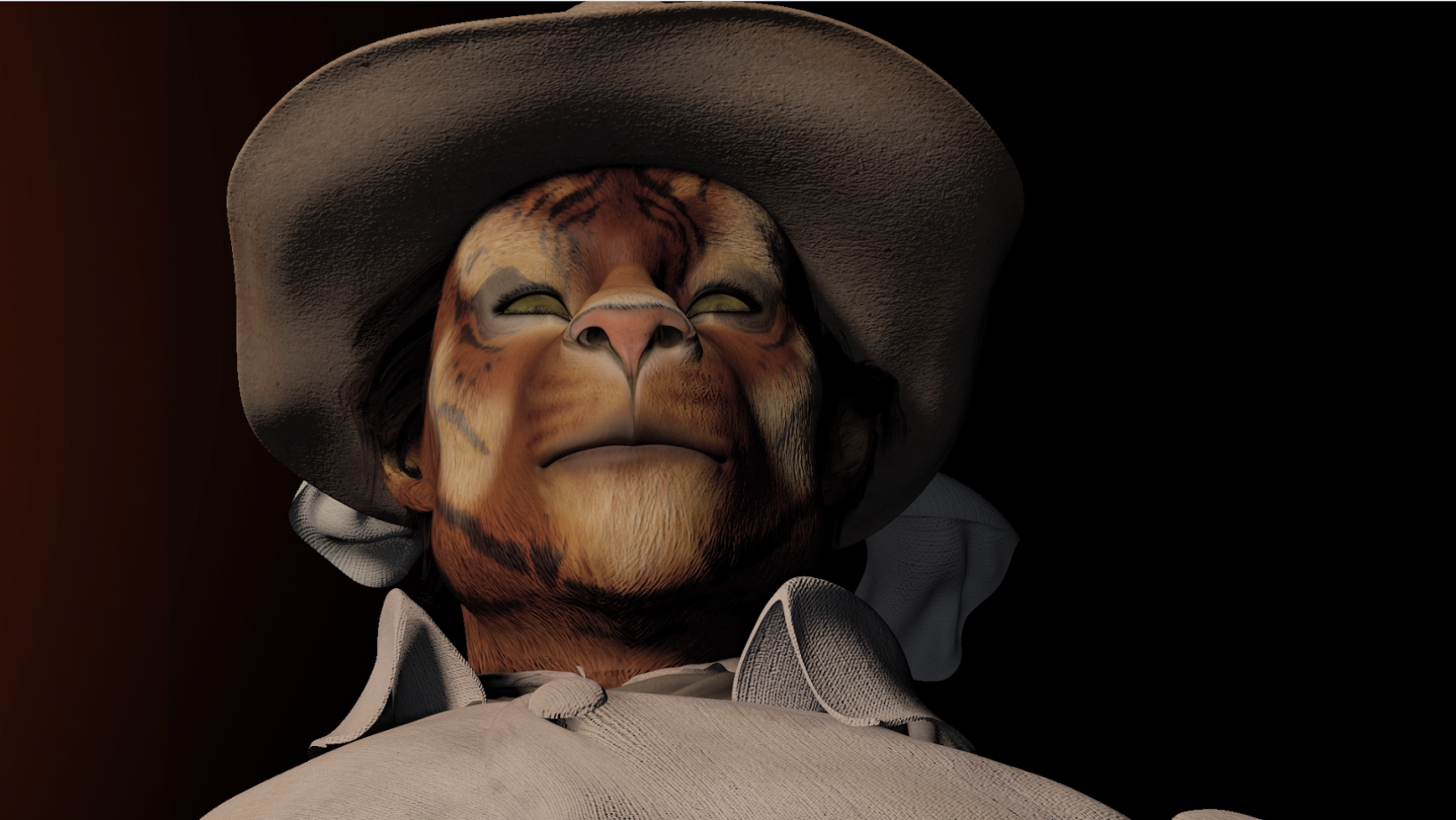

One or Several Tigers consists of two screens facing each other in which the video animation is projected. It takes the form of a duet between a man and a tiger, narrated across these two screens that respond to and complete each other. The work begins with an ancient past, long before the emergence of Homo Sapiens. At that time, says the voice-over, tigers already existed and roamed across the Sunda Shelf. On one screen, the fundamental elements air (the sky), fire (the sun), the earth and water (the sea) alternate while on the other screen the image features a close-up of an eye’s iris reflecting those changing landscapes. Immediately we feel transported in the mythical times where all narrations originate: it is night then dawn then night again. Under the moon light, the tiger appears and, as the camera slowly moves back, we can recognize that the eye belongs to a human face. For the first time, thus, tiger and man face each other on the two opposite screens. Quickly, the narration loses its chronological path and, like tigers, jumps to and from various historical events without following the usual timeline. After the history of tigers and a presentation of weretigers, the artist – through the voice-over - addresses the colonization of the Malay world and how it impacted tigers, both literally and metaphorically. In particular, a long sequence is dedicated to the arrival of the British colonizers in Singapore, and their encounter with a tiger in the jungle in 1835 as depicted by Heinrich Leutemann’s engraving. The figure of the man, who hitherto represented human beings in general, is now embodying George Dromgold Coleman. The characters play the scene of the drawing as if the tiger was really attacking. We can thus feel the tension, fear, and the suspense as the sun, burning, seems to crackle. “I sprang for the machine,” says the tiger and the theodolite device infiltrates and breaks the tiger/man duo, as with colonization and civilization that interfered in their genuine relationship. The next part, or fragment as the artist put it, stages Skeat’s photograph and we then jump to 1942 with the “Tiger of Malaya,” the General Tomoyuki Yamashita. “Full of guile in battle, the Japanese forces seem to embody the very qualities that had made the tiger such a feared adversary of the early British settlers,” says the voice-over. From this Japanese “revenge” on the British, we go back to early colonial Singapore in order to focus on the Indian convicts, who witnessed the tiger’s attack of the theodolite, and who were building the city and its prisons. They were sent from India across the sea in a journey of no return that they referred to as the “kala pani,” or “black water.” As told by the voice-over, their former lives were to be dissolved, “like water in water.” This fragment parallels the colonial period with present-day Singapore: Leutemann’s engraving, displayed today at the National Gallery Singapore, is filmed from afar while a group of migrant workers come to contemplate it as if they were reflecting on their own past. Finally, in the last two minutes of the animation, the story goes back to Java in Indonesia and briefly hints at the traditional Javanese rituals of rampog macan.

Still image from One or Several Tigers (2017). (face of General)

Ho does not like to stick to chronological linearity as he prefers “jumping from different points in time in order to generate a maximum of associations, resonances and intensities.” He also always favors horizontal approaches to narratives, avoiding any climax. In this flattened structure, transitions are purposely not always easy to grasp: for example, General Tomoyuki Yamashita borrows his clothes and body form from Coleman, and the way they move and relate to the tiger are similar. The only difference is their face: the Japanese soldier’s face slowly transforms into a tiger’s face. There is no change in the background that could contextualize either the epoch they are coming from. All characters, like puppets, have in fact been extracted from their time so that they can connect differently. The only link they keep is the 1865 drawing, and, beyond, their connection to tigers and to the cosmic elements they seem to originate in. This structure allows to highlight some historical recurrences and in particular to emphasize the constant inequal power relations established by dominant classes, be they colonizers or capitalists. We can thus switch smoothly from British colonization to the 'Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere' project developed in Japan from the end of the 19th century in response to European imperialism. [32] The connection to the present-time raises also the question of the concept of “post-colonialism.” As pointed by Ann Laura Stoler, “colonial toxicities” can still be felt today as there are deeper, tenacious and durable manifestations of colonialism that persist. For the professor of anthropology and historical studies, the term “postcolonial” does not indeed mark a “time period but a critical stance,” and there is no clear line that would separate a colonial from a post-colonial time. [33] With his fragmented and non-linear approach of history, Ho emphasize these connectivities and the recursive feature of history, in particular as expressed in Singapore today’s working class.

Still image from One or Several Tigers (2017). (engraving background)

Still image from One or Several Tigers (2017). (screen lifts up)

The non-linearity is also represented by the artist’s inclusive combination of techniques: Ho juxtaposes layers of proto-cinematic and post-cinematic technologies as a way to combine and reconcile traditional and technological mediums on the one hand, and Western and Asian techniques on the other. Most of the work is digitalized video animation yet the work also includes film footage, video’s fragments and shadow puppetry. In the last part of the video, in particular, one screen lifts up to reveal a set of shadow puppet theatre carved out from buffalo-skin and replicating Leutemann’s engraving. For Ho, shadow puppet theatre is the Asian equivalent of Western cinema except that the projection comes from the back. He plays with both and creates multiple visual effects according to whether the screen is illuminated from the back or from the front. The shadow stands also for the workers’ labor and for the ancestors’ spirits that turn into tigers. In any case, it embodies the identity of all the people and creatures that live in invisible worlds. This original apparatus features images within images, representations of representations in an endless “mise en abîme,” in which we might only meet shadows and symbolic forms. In many of the artist’s performances, curtains lift up in the end only to reveal empty puppets, suggesting there is nothing but illusion – or the void, behind our objects of representation.

Metamorphosis and fluidities

In the installation, the viewers sit in between the two screens and follow the duet by alternatively watching one of the screens. The idea of duality is thus immediately perceptible by this constant interplay, yet the characters often switch roles and places from one screen to the other. At soon as weretigers are conjured up, the bodies duplicate: a tiger emerges from the man’s body and conversely. Their shadows also combine while their features constantly evolve and juxtapose.

Still image from One or Several Tigers (2017). (Coleman and tiger)

For Ho, as with many people from Southeast Asia, the distinction between humans and non-humans is a characteristic of Western modernity that he wishes to move away from.[34] In the work, the images of the tiger and of the man constantly melt and transform. Weretigers are obviously the emblematic figure of such metamorphosis but metaphorically, tigers can be found everywhere and under any shape. The technique of digital animation allows for these morphings to unfold naturally. Digital animation and images originate from data and from the transformation of information. The process of metamorphosis is already at stake here: reality is transformed and reborn in a new virtual sphere cut off from its reference. It is projected on a screen and not printed on a surface and has no materiality as all. In the work, the figures’ bodies can be thus perceived as mere containers or envelops that can be filled at will. In many indigenous animist beliefs, physical bodies are precisely conceived as envelopes that are interchangeable: they are like clothes that one can borrow for a period of time. In order to shed light on the generic nature of his characters, their animated figures and facial expressions have been captured by the movement of a single performer, the musician and singer Vindicatrix. Beyond their various appearances, all the bodies could thus become one. Their disconnection with a tangible reality is also conveyed by their slow motion and floating movements: during the recording, the performer was in fact suspended from the ceiling and moved in the air. Hence, the featured figures have no gravity, and they can swell like balloons and drift or dissolve into space.

The soundtrack of the animation mirrors this interspecies fluidity. The story is told by a voice which does not sound totally human. It whispers, resonates and trembles successively, sometimes resembling a chant, a prayer or a plaint. In fact, it is a combination of the man and the tiger’s voices, performed by Vindicatrix. It also performs the chorus, which are lines that belong neither to the tiger nor to the man. Later, their voices dissociate but occasionally rejoin again, especially when tigers and human beings dissolve into each other. These voices melt with the sound of the environment as well, embracing the rustling from the forest, the splashing of the sea or the vibrations of galloping animals on the land. The voice of the man is deep while the gamut of the tiger’s voice is larger, and its tone is rather high or guttural. The words are not always decipherable and are often repeated alternatively by the tiger or the man. In the end, who is narrating this story? It is impossible to tell. As for the subtitles, they jump from one screen to another as if they were independent.

The installation is organized so that the viewer sits in between the opposite screens and, as such, cannot see the whole work but only a part of it. In fact, who could read both sides? For Ho, only non-humans such as spirits or gods could. “I have always considered the true audience of this work not to be the human subject - the human subject can only be passing through, or a partial witness of an event that stretches beyond him / her.”[35] From this perspective, the work unfolds in multiple ways for different types of public to be reached. In the end, when all the migrant workers are in the museum, they suddenly turn back after having contemplated the engraving, as if they had been called by someone or something. Perhaps they respond here to an invisible presence… The smog, released alternatively from behind the screens, adds to this mysterious impression and favors the idea of transformations and intangibility.

Still image from One or Several Tigers (2017). (migrant workers in the Museum)

Beyond its ecological and ontological features, the process of metamorphosis is also political and embodies the recursive dimension of history: the feared figure of the tiger, whatever its incarnation, stands as a constant force throughout time. When the migrant workers turn back, we actually discover that a weretiger infiltrated their group. Since this fragment is not an animation but a real film, this apparition is very surprising and suggests again some passages between the visible and invisible worlds. It is unclear what were the artist’s intentions, but this last metamorphosis may refer to a form of resistance that could inhabit these workers. The figure of the tiger remains indeed ambiguous as it oscillates between domination and resistance. One could wonder who today’s tigers are, but this question is kept open. The constant state of suspension generated by the animation prevents in fact any form of violence from arising: in the video, there is no moment of confrontation, no clash. The underlying violence is only expressed by changes in the sound rhythm or flashes of images, creating thus a permanent tension that never blow out.

Conclusion

One or Several Tigers is the artist’s last variation and iteration around the same theme (the real and symbolic relationships between men and tigers). It exemplifies Ho’s “crystallization” of his research findings as one can trace back how the artist has deconstructed and re-assembled his data material into an entwinned constellation of sounds and visual expressions. His use of various techniques reflects the artist’s search for hybrid forms of languages that would change our usual relationship to reality and generate an alternative form of knowledge.

“In man, there live two animals that never coincide. The first is made of words. And the second is made of flesh.”[36] As argued by the tiger, an incompressible duality seems to oppose the verbal discourse and more sentient forms of languages. In his creative practice, Ho aims precisely at breaking this duality, operating a convergence between these two spheres by transforming the data he has collected into multi-sensorial modes of expression that would not be recuperated by mere communication purposes but that would, on the contrary, open up new possibilities to apprehend the world. This is also what Roland Barthes was seeking when he approached the Japanese culture and dreamt of an alien language that he would know but not understand. A language that would allow “to undo our own “reality” under the effect of other formulations, other syntaxes.”[37] What Barthes describes here resembles poetry, and this is probably a kind of poetic language that Ho is also experimenting, although through a more complex juxtaposition of mediums. The artist does not totally wish to depart from a common language either and, through the use of subtitles, we have seen how he maintains a consistent narrative that often quotes scholarly literature. The contextual background is also clearly explained, key dates and biographies are enounced as well as hints to decipher the projected images.

For Barthes, the pleasure of a text derives from a “cohabitation of languages” that creates vacillations and that destabilizes the readers. [38] With his non-linear, open-ended and fragmented mode of expression, Ho embraces as well uncertainty and confusion in order to move away from fixed paradigms. His dense verbal narrative, although clearly articulated, is indeed too excessive to be really understood. As noted by the artist, no one can read simultaneously the subtitles from both screens, and since the sentences are sung, the words are actually not always decipherable. From what he calls this “excessive verbiage,” Ho wishes in fact to create a sense of emptiness as if this density could collapse into a form of nothingness. Void, here, should not be understood as the opposite of “full” but as a living space open for creativity. From there, the viewer’s imagination could wander freely and go astray, disengaged from any established form of language and guidance.

Hence, by shedding light on the artist’s relentless attempts to free himself from arrested modes of representation and of knowing, One or Several Tigers underlines the complex negotiations going on between art’s cognitive and aesthetic dimensions in research-based art practices. However, for Ho, these two dimensions are not mutually exclusive and they complement each other. In particular, the artist explores inclusive and dynamic modes of thinking in which the knowable and the unknowable can cohabit: they belong to the same chain of experiences that, progressively, and through uncertainty, trials and errors, leads to a critical approach of reality and according to which knowledge never refers to an immobile object of study but should be conceived as a trajectory or as “a vector of transformation.”[39]

Still image from One or Several Tigers (2017). (Coleman and the moon)

[1] The Encyclopedia Britannica includes 11 countries in Southeast Asia (Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Timor-Leste and Vietnam).

[2] More on the Critical Dictionary of Southeast Asia and Southeast Asia’s essence, see Ha Thuc Caroline, “What is Southeast Asia? Emancipatory modes of knowledge production in Ho Tzu Nyen’s Critical Dictionary of Southeast Asia,” South East Asia Research Journal, Vol 29 (2):2021.

[3] For Ho, Southeast Asia is emblematic of the periphery of the periphery: located in Asia, it used to be at the periphery of the Western world, and being in the south, it is a periphery of Asia, caught up between India and China.

[4] This article is based on conversations with the artist having taken place in Hong Kong, Singapore and also by emails from March 2019 to November 2020.

[5] Boomgaard Peter, Frontiers of Fear: Tigers and People in the Malay World, 1600-1950 (Yale University Press, 2001), 116.

[6] Boomgaard, Ibid. 2001, 29.

[7] See Ma Huan, The Triumphant Visions of the Shores of the Ocean. The Chinese traveler, who served under navigator Admiral Zheng He, described tigers transforming into humans in Malacca.

[8] On the British colonial hunting practices, see for instance Mac Kenzie John, The Empire of Nature: Hunting, Conservation, and British Imperialism. (Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, I988) and Hussain Shafqat, “Tiger and Markhor Hunting in Colonial Governance,” Modern Asian Studies, Vol. 46(5) (Sept. 2012): 1212-1238.

[9] More on these rituals, see in particular Boomgaard Peter, “Tiger and Leopard Rituals at the Javanese Courts 1605-1906,” in Frontiers of Fear: Tigers and People in the Malay World, 1600-1950 (Yale University Press, 2001), 145-166.

[10] The first newspaper report was in 1831. See Barnard Timothy, “The Tiger Club: Excerpts from Accounts of Tigers in 19th-Century Singapore,” in Tigers of Colonial Singapore (Singapore: NUS Press, 2014).

[11] For a history of Indian workers in Singapore, see in particular Rajesh Rai, Indians in Singapore 1819–1945: Diaspora in the Colonial Port City (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2014).

[12] Chua Kevin, “The Tiger and the Theodolite George Coleman’s Dream of Extinction,” FOCAS Forum on Contemporary Art & Society 6 (2007): 131.

[13] Heinrich Leutemann (1824-1905) was a German artist and book illustrator known for his drawings of animals. Interestingly, he never went to Singapore but created an atlas of animals from all over the world.

[14] The incident was notably described by historian of the environment and culture of Southeast Asia Timothy Barnard, who questions its authenticity. See Barnard Timothy, Tigers of Colonial Singapore (Singapore: NUS Press, 2014).

[15] See for instance the memoirs of John Frederick McNair who was responsible for Public Works and who was also the Superintendent of Convicts in the region. Mc Nair John Frederick, Prisoners their own warders a record of the convict prison at Singapore in the Straits Settlements, established 1825, discontinued 1873, together with a cursory history of the convict establishments at Bencoolen, Penang and Malacca from the year 1797 (1899).

[16] Chua Kevin, “The Tiger and the Theodolite George Coleman’s Dream of Extinction,” FOCAS Forum on Contemporary Art & Society 6 (2007): 142.

[17] In 2020, Ho collaborated with one of these migrant workers, Ripon Chowdhury, for a short video entitled Waiting (2020) created in response to the Covid and reflecting on how these workers were confined in their dormitory

[18] Wessing Robert, The Soul of Ambiguity: The Tiger in Southeast Asia. Monograph Series on Southeast Asia Special Report No. 24 (Center for Southeast Asian Studies, North Illinois University, 1986), 1.

[19] In a 1946 interview for the New York Times, for example, Ho Chi Minh compared the people from the Viet Minh – the communist Vietnamese resistant organization - to tigers who can defeat the mighty elephants (the French colonial) by jumping on their back. From Montagnon Pierre, L’Indochine française (Paris: Tallandier 2016), 221.

[20] Chua, 2007 Ibid. 139.

[21] Wessing Robert, “Symbolic animals in the land between the waters - Markers of place and transition (Symbolic animals in Indonesia and Southeast Asia),” Asian Folklore Studies, Vol65(2) (2006): 205-239; Wessing Robert, “The Last Tiger in East Java: Symbolic Continuity in Ecological Change,” Asian Folklore Studies, Vol54 (1995): 191-218.

[22] For example, Akashi Yogi, New Perspectives on the Japanese Occupation of Malaya and Singapore, 1941-45 (Singapore: NUS Press, 2008) and Comber Leon, 'Traitor of all Traitors' - Secret Agent Extraordinaire: Lai Teck, Secretary-General, Communist Party of Malaya (1939-1947),” Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, Vol. 83, No. 2 (299) (December 2010).

[23] Yeoy Joe, To Tame a Tiger, The Singapore Story (Wiz-Biz edition, 1995).

[24] Email interview with the artist, April 2019.

[25] Bataille’s essay is commented by Canadian philosopher Etienne Turpin whose 2014 essay “Why were there tigers?” was also influential for the artist.

[26] Deleuze Gilles & Guattari Felix, A Thousand Plateaus, trans. Brian Massumi (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987). More on the artist’s rhizomatic work approach, see Ha Thuc Caroline, “What is Southeast Asia? Emancipatory modes of knowledge production in Ho Tzu Nyen’s Critical Dictionary of Southeast Asia,” South East Asia Research Journal, Vol 29 (1):2021.

[27] The image comes from Walter William Skeat's book Pagan Races of the Malay Peninsula published in 1906.

[28] With the exception of Ho’s collection of books written by Gene Z. Hanrahan, displayed as part of the work The Name (2015).

[29] Ho Tzu Nyen, “Every Cat in History is I,” FOCAS Forum on Contemporary Art & Society 6 (2007): 150-167.

[30] Bourriaud Nicolas, Postproduction (Lukas & Sternberg, New York: 2002).

[31] Bourriaud 2002, Ibid. 18.

[32] Tarling Nicolas (ed.) “Southeast Asia in War and Peace in the end of the European colonial Empires,” in The Cambridge history of southeast Asia, vol. 2 (Cambridge University Press, 1992), 333.

[33] Stoler Ann Laura, Duress. Imperial Durabilities in our Times (Durham, London: Duke University Press, 2016), 5.

[34] Animism used to be the dominant beliefs among hill people from Southeast Asia. See for instance James C. Scott, The Art of Not Being Governed (Yale University Press, New Haven & London: 2009).

[35] Email conversation with the artist, December 16, 2020.

[36] Quotation from the animation video.

[37] Barthes Roland, The Empire of Signs, translated by Richard Howard (New York: Hill and Wang, The Noonday Press, 1982 [1970]), 6-7.

[38] Barthes Roland, The Pleasure of the Text, translated by Richard Howard (New York: Hill and Wang, 1975 [1973]), 3-4.

[39] The concept comes from French philosopher Bruno Latour. See in particular Latour Bruno, “A Textbook Case Revisited - Knowledge as a mode of existence,” in Vie et Expérimentation Peirce, James, Dewey, edited by Didier Debaise (Paris: Vrin 2007): 17-43.