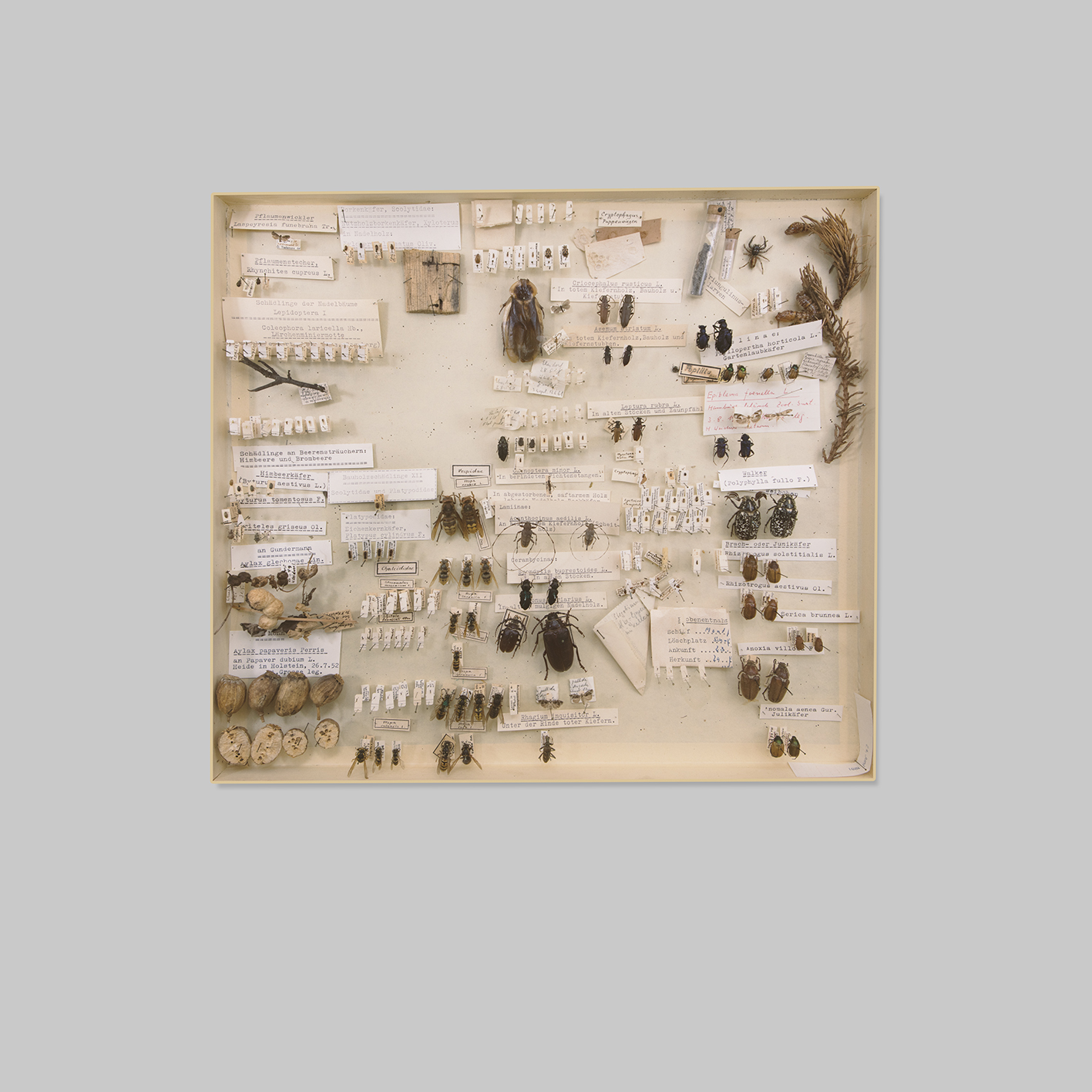

Robert Zhao Renhui: When Worlds Collide (2017-2018) and the Institute of Critical Zoologists

Robert Zhao Renhui, Rock Pigeon (Columba livia), diasec inwooden frame 42x29.7cm, 2018

All images courtesy of the artist and ShanghART Gallery.

When Worlds Collide (2017-2018) is amultimedia installation created by Singaporean artist Robert Zhao Renhui(b.1983) for the 2018 Taipei Biennial.[1] The work, which is theartistic documentation and outcome of the artist’s fieldwork in Taiwan, Greece and Germany, questions our paradoxical and complex relationship with nature and animals against the backdrop of globalization, massive flux of migrations and rapid urbanization. It mainly consists of photographs and artefacts related to insects, pests, amphibians and birds displayed as if they were part of anatural museum’s collection.

The installation is presented by The Institute for Critical Zoologists (ICZ), a creative scientific and pluri-disciplinary platform founded by Zhao in 2008, officially initiated in 1996 by a Japanese and a Chinese researcher after the merger of two scientific institutes. Developing a critical approach to the field of zoology, it mainly aims to “advance unconventional, even radical, means of understanding human and animal relations.”[2] Mixing openly fiction and reality, Zhao creates most of his artworks under this umbrella and meticulously catalogue them within the institute’s website.[3] His research practice is dedicated to the study of the natural world and of its various andcomplicated interactions with humans.

The originality of When Worlds Collide lies in the juxtaposition of the artist’s different research findings that creates critical narratives and brings forth contradictory perspectives about human conceptualizations of nature and environmental policies. The discursive part, expressed through the texts that accompany the artworks, plays a key role to support and link these narratives, while the artist’s curation and framing ofthe artworks exacerbate the paradoxical gaps that still separate humans from non-humans.

Contextual framework and artist’s drive

Fighting invasive species

In Taiwan, Zhao delved into the governmental incentives thate ncourage the eradication of invasive species and aim at preserving the local native biodiversity. Invasive species have been defined as “species that establish a new range in which they proliferate, spread and persist to the detriment of the environment.”[4] These invasions are not a new phenomenon, but they have drastically increased along with globalisation and, today, few if any places remain free of migrant species introduced by human trade and transport. Taiwan, in particular, is more subject to the threat of invasive species because of its specific insular ecosystem. It is for example among the places that are the most affected by invasive species of amphibians and reptiles.[5] In response, the government has implemented a series of removal plans focusing on specific species of lizards, frogs and on the African sacred Ibis.[6]Residents can for instance receive a prize for capturing or killing exotic lizards such as the green iguanas who were mainly introduced as pets in the island, but whose huge size, when adults, has pushed many owners to abandon.[7] Similarly, a 2011 removal plan encourages residents and volunteers to report spotting spot-legged tree frogs,a species of frog originated in India and Indochina which has a strong reproductive ability and no predators, and which thus competes with native frogs.[8] During his fieldwork, the artist participated in such a hunt with volunteers from the Taipei Zoo.

Robert Zhao Renhui, Green Iguana (Iguana iguana), diasec inwooden frame 60x40cm, 2018

The real impact of these policies remains to be assessed as well as the real impact of these invasive species on the local biodiversity. In the case of the Sacred Ibis, for example, “environmentalists have yet to find any evidence of it harming the local ecology,”[9] and there is no evidence of the iguana directly threatening the native ecosystems, although people are worried about its impact on crops and agriculture.[10]The objectives of the removal plans, thus, can be confused: here, restoring the native ecosystem seems to be mixed with more human and economic concerns. When can we classify a species as a threat, and under which criteria? In fact, aspecies can even be qualified at the same time as a threatened species in some places and as an invasive pest somewhere else.[11]

An ambiguous issue

In his statement, Zhao recalls the anthropocentric perspective of these controls, with the spread of invasive species being largely a human consequence.[12] His work is a response to the lack of critical views that would question this apparent consensus. For him, the killing of non-human species in the name of protecting other non-human species deemed more valuable is problematic. Why would native species be morevaluable than the others, and why would humans make the decision rather than letting nature decide? Zhao does not have answers to these complex questions, since every case is unique and highly contextual, yet, as an artist, he feels the need to raise them critically.

Robert Zhao Renhui, Christmas Island, Naturally II, from the series Christmas Island, Naturally. 150x100cm, diasec in frame, 2015.

Zhao already addressed the issue in a 2015 work focusing on the ecology and ecosystem of the Christmas Island in the Indian Ocean.[13] Most the island has been transformed into a natural reserve, with its inhabitants relocated, in order for the scientists to study its exceptional endemic flora and fauna, relatively preserved despite 150 years of human interactions. The artist is fascinated by the human desire to control the evolution of nature and to deny its own inherent changes, as if nature was a static entity. “We all want to protect nature but we do not seem to know what is natural and what is unnatural.” He also notes that, after a while, some alien species can become ‘naturalised,’and thus cease to be seen as a threat.

“I think only humans think about nature in terms of life and death. In the natural world, life carries on in ways like a cycle. We should perhaps start to think that nature has a way of its own. When animals invade a space and thrive, it usually means that the system is already broken.” In fact,“novel ecosystems”can emerge,[14]with a thriving hybrid biodiversity that has been called a “new wild.”[15] This perspective stands against the viewpoint of conservationists and restoration ecologists who try to restore ecosystems as they originally were, and do not consider the resilience of nature and its ability to evolve and adapt by itself.

Besides, to which ecosystem are we referring to when it comes to preserving its native condition? In the United States, for example, restoration ecologists try to eradicate or to limit the growth of invasive species in order to return damaged ecosystem to “the condition of the ecosystem prior to thearrival of Euro-Americans.”[16] These choices are obviously debatable, and highly political.

An ambivalent relationship with nature

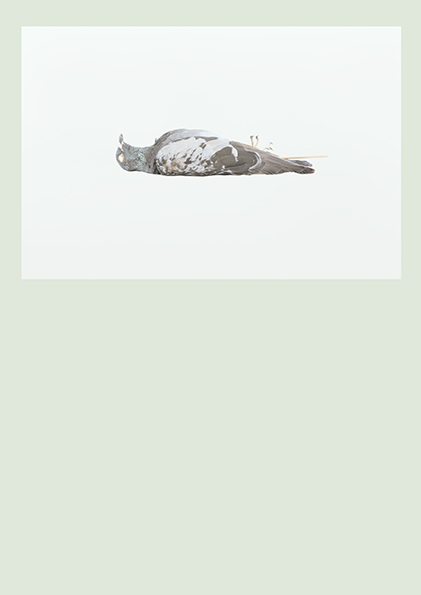

The fight against invasive species reflects specific and constructed human conceptualizations of nature and what it should or should not be like. In parallel to these ecological endeavors, many insects continue for instance tobe deemed useless and harmful to humans, and, as such, are targeted to be destroyed. This is especially the viewpoint of German entomologist Herbert Weidner (1911-2009) who categorized insects according to their nuisance, warning that one should destroy them all thanks to pesticides in order to secure human future.[17] He collected and scrupulously classified more than 200 objects such as pieces of furniture orboxes of chocolates that carry the evidence of the pests’ deleterious activities, reflecting what Zhao calls a “paranoid obsession.” An important part of the installation When Worlds Collide is a documentation of this collection, which the artist discovered during his residency in Hamburg.[18]

Robert Zhao Renhui, Animals That Threaten Us, Unsorted Tray 18, diasec in wooden frames 30x30 cm, 2018

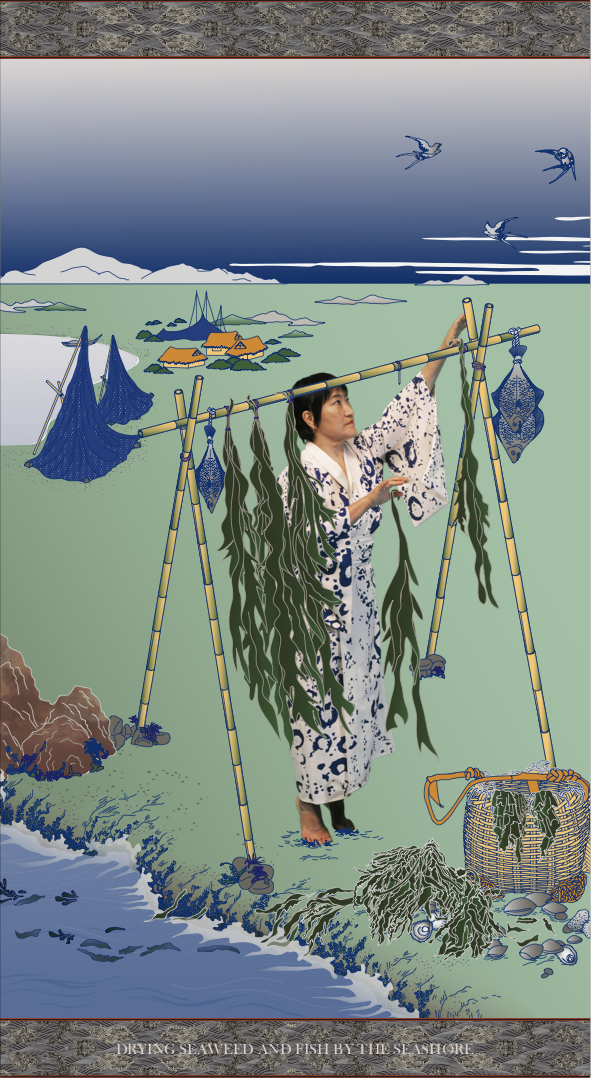

To complete the scope of today’s ambivalent and complex human relationships with nature, Zhao includes in the installation the outcome of his research in Athens and Taipei related to urban injured birds. In both places, people are picking up injured birds and bring them to wild animal rehabilitation centres where they can be healed. Some have been hit by a car or a window from a glass building, but others have been shot by citizens. They represent the collision suggested by the installation’s title when the human and the natural worlds collide, especially in contemporary urban environments.

In the three cases, and beyond existing environmental discourses, non-humans remain under human control, even if it is for “good” reasons, perpetuating the nature/culture Western divide. For the artist, there is no such a line that could separate these two worlds which are continuously entangled in an increasingly complex, dynamic and interdependent relationship. When Worlds Collide expresses these paradoxes and tensions.

A Singaporean context of work

Robert Zhao Renhui, The Nature Museum, exhibition view. Singapore International Festival of the Arts, 2017.

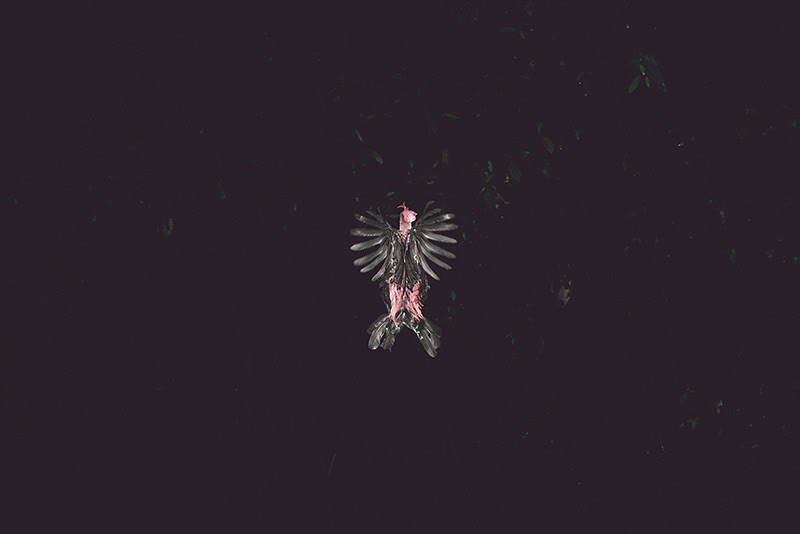

Singapore, where Zhao lives and works, is known for its policies aiming at greening its environment and, despite its high development and urbanization, it is proud to have become a green and clean “Garden City.”[19] This environment is a continuous source of inspiration for the artist who spent years studying the evolution of Singapore’s specific fauna and flora. The Nature Museum (2017) consists for example in an installation of documents, archives, artefacts, specimen and artworks dealing with the natural history of Singapore Island from the late 19th century onwards. Beyond its colonial past, Zhao’s observation of nature in the city reveals again the complexity and often paradoxical relationships between human and non-humans, with a permanent will to control the city’s environment. The photograph The rooster will crow three times echoes especially the topic of When Worlds Collide: it shows a red junglefowlbird flying just before it was killed by local residents, who complained about its noise.[20] This species, an ancestor of our common chicken, was nevertheless a former extinct bird species native from Singapore, which recently came back due to the environmental incentives.

Robert Zhao Renhui, The rooster will crow three times, photograph, 2017.

These local policies are mainly conceived to woo investors, and, for Zhao, nature is turned into a utilitarian object, a necessary decoration that does not have any autonomy anymore. “In Singapore, almost every tree in the city is registered.[21] We all want to contribute meaningfully to nature but we have to be in control. One can see pest extermination vans all the time, as if residents were under attack. I am interested in the unpredictable stories that turn up in Singapore between humans and nature.”

Zhao’s father grew some hundred bonsais, a passion which could epitomize the art of controlling nature. The artist himself has always been fascinated by nature and used to photograph animals in captivity at the Singapore zoo before building narratives that expanded his approach of nature under the umbrella of the Institute of Critical Zoology (ICZ). He studied at Temasek Polytechnic in Singapore and graduated from the Camberwell College of Arts and then from the London College of Communication at the University of the Arts, London, where he studied photography.

The artist-researcher

A non-scientific perspective

At first sight, the ICZ looks authentically scientific and Zhao’s research accurate. All images and materials are well-documented, including Latin names, scientific descriptions and contextual backgrounds. Each topic seems to be approached from a systematic and almost encyclopedic perspective.The website of the institute offers even the possibility to join the team and suggests that visitors could visit the labs of the Institute.

One critic wrote: “Zhao is best known for the sly pseudo-documentarian imagery that appears as ‘research’ under the auspices of his fictive Institute of Critical Zoologists.”[22] Here, the quotation marks around the word research points to the doubts that the artist has introduced when it comes to categorize his practice where the line between reality and fiction is purportedly blurred. His photographs indeed used to document false exploration journeys undertaken by fake researchers or study groups, and delves into collections created by imaginary scientists who excavate new species or invent new natural taxonomies.[23] However, at the same time,the artist keeps collaborating with real scientists and museum collections, guided by a genuine passion for natural history. Unlike Kusno’s Centre for Tanah Runcuk Studies,[24] there is no disclaimer and a scientific magazine famously published one of the artist’s photographs including his research outcome, although it was a mere artistic creation.[25] In fact, Zhao is not interested in any form of credibility and does not define himself as a researcher nor as a scientist. “I do not think my research helps in our understanding of nature as a scientist would. I think science limits the experience I can have for my projects, and I believe in a wider perspective of things.” For him, what matters the most is to find the right way to address specific issues, and this perspective often involves creating fictional narratives.

Robert Zhao Renhui, White-lipped Tree Frog (Polypedates braueri), diasec in wooden frame 40x60cm, 2018.

2018

When Worlds Collide does not include any fictional elements, yet the artist continues to borrow freely the language of science. The text that accompanies every artwork describes the story of the photographed specimen, including their scientific names, and explains how they are connected to the exhibition. One can read, for instance, that the sacred ibis (Threskiornis aethiopicus) originates in Egypt, escaped from a Taiwanese zoo in 1984 and since then multiply in the wild. There are no scientific references, though, and the artist does not mention his sources nor his methodology of work either. For him, a scientific framework allows him to legitimize his personal approach to nature, since “amateurs or pets’ lovers”would not be taken seriously. The part of the exhibition dealing with Taiwan is for instance ambitiously entitled “A Guide to the Fauna of Taiwan,” a title supposed to bestow some legitimacy to the work. The installation is obviously not that exhaustive and the reference is above all ironic since the fauna it refers to deals with the species that are eradicated by the governmental policies.

More generally, the installation’s display mimics classical Western natural history exhibitions while the framing and staging of the photograph simitates naturalists’ shots and their apparent and systematic objectivity. Most of them have actually been taken from museums, from stuffed animals, in collaboration with the local institutions, because Zhao did not have the time to photograph all species in the open air. The few elements of parody seem to indicate that the artist keeps a critical distance from these conventional and old-fashioned methods of representation. However, the work does not directly question these scientific norms and thinking frameworks, or even the legitimacy of documentary photography. What is challenged is rather human’s persistent representation of nature shaped by these old models inherited from Western modernity that carried the dream to classify, understand and thus control nature. The scientific language is not diverted but used as a framework to stage the artist’s narratives and eventually contextualize it within the widerscope of natural history.

Prevalence of fieldwork

When Worlds Collide is the artistic outcome of Zhao’s research field trips in Hamburg, Athens and Taipei.[26] Conceptually, a few reference books have been very influential for his research, such as environment writer Fred Pearce’s New Wild, Professor of environmental geography Ian Rotherham’s Invasive and Introduced Plants and Animals, American permaculture designer Tao Orion and Japanese farmer and philosopher Masanobu Fukuoka’s works.[27] Before his residencies, the artist also made research on the Internet in order to get a sense of what could be done locally and to grasp the contextual background of the places. However, fieldwork remains the most important part of his work as he prefers having first-hand information from conversations and experiences rather than superficial stories from the Internet. “Almost immediately when you speak to people, they would tell you something that the Internet had misinterpreted.” Thanks to these conversations, with local scientists, environmentalists, activists or volunteers, he also discovered stories that he could not have found by himself.

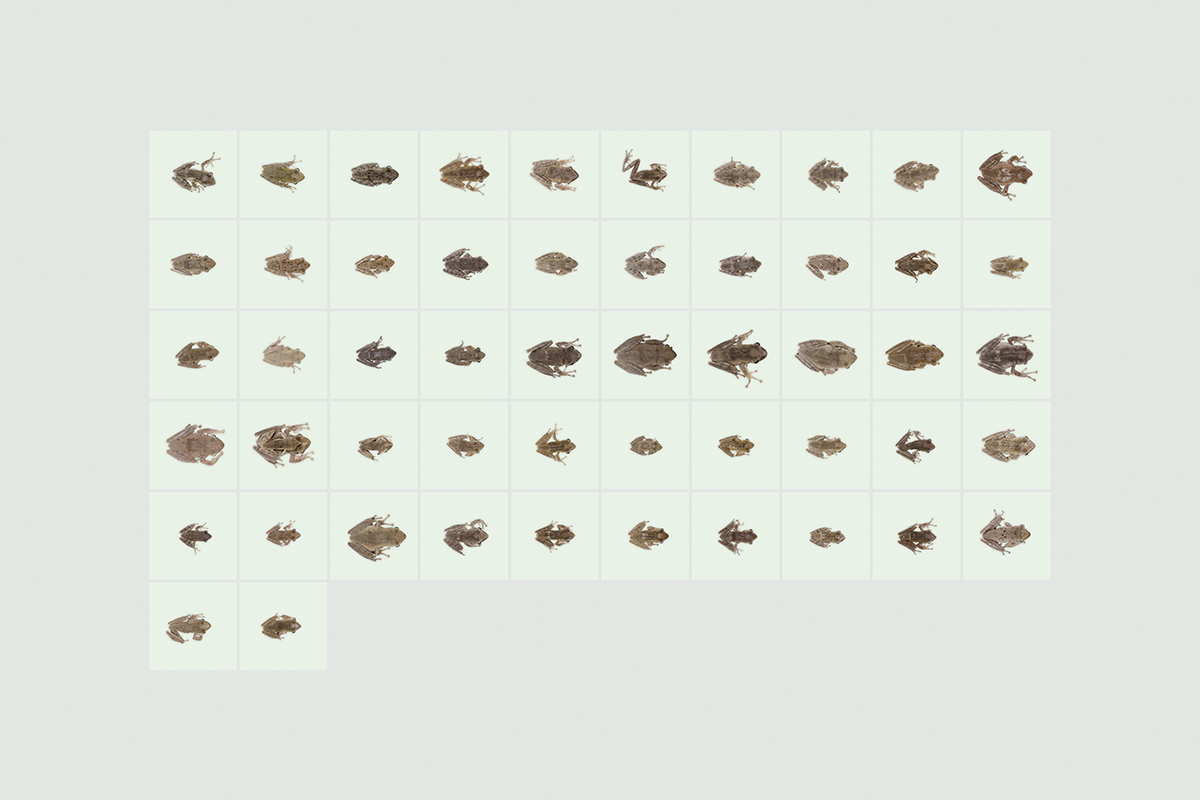

Robert Zhao Renhui, Spotted Tree Frogs (Polypedates megacephalus)collected in a single night, diasec in frame, 74x111x6cm, 2018.

Zhao’s fieldwork could be divided into two separated yet connected activities: visiting local institutions dealing with natural history and engaging in activities related to the local fauna and flora. The photographs from Taiwan come from the collections of various institutions such as The Endemic Species Institute, the Dong Hua University or The Wild Bird Society of Taipei. Zhao participated also two times in an invasive frog hunting with volunteers from the Taipei Zoo. They caught more than 50 frogs, photographed by the artists, which were later given to feed the zoo animals. For him, it was important to be part of these kinds of practices. He realized how much the native species have become rare and his approach of the issue took a more embodied perspective. Discussing with the volunteers, who commit very seriously to their task of preserving native frogs, allowed him to better understand their motivations.

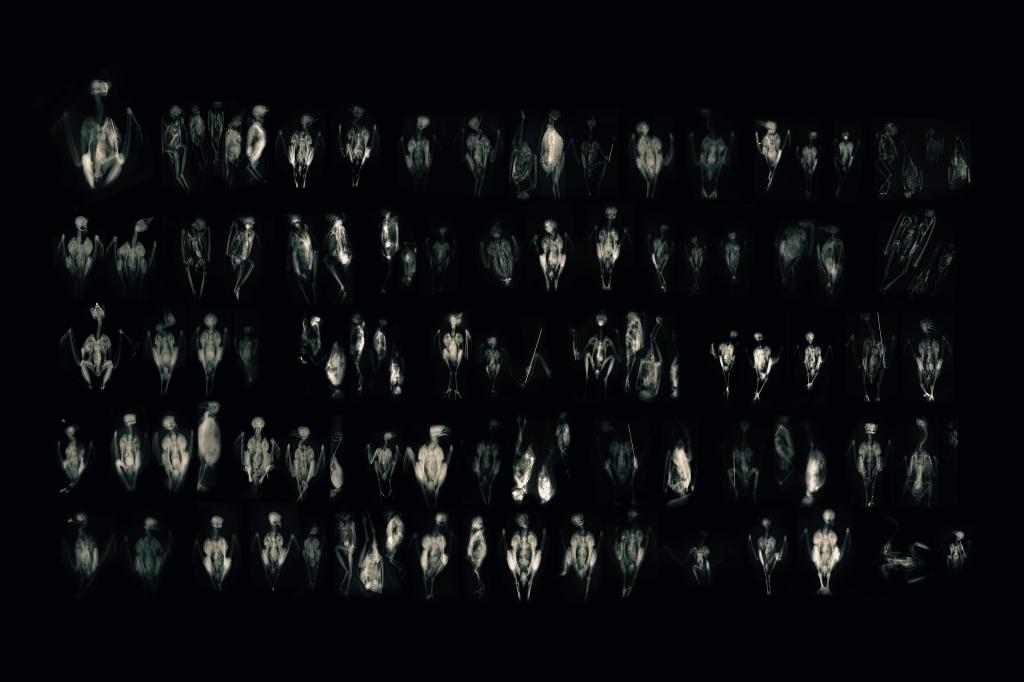

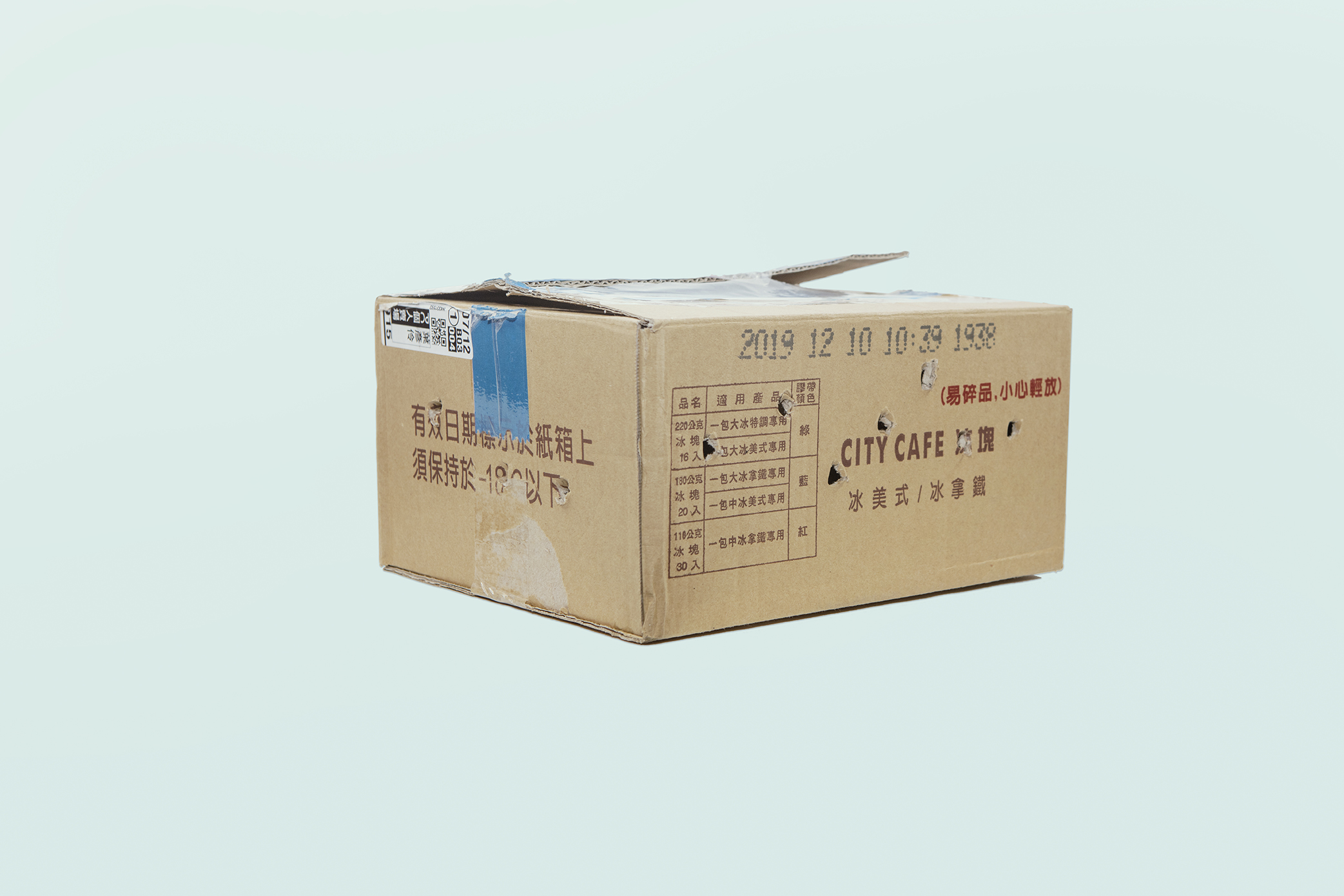

In Athens, Zhao got involved with ANIMA, or Wild Life Conservation Society, where injured birds can be rescued.[28] It gave him the sense of the number of injured animals that are delivered by volunteers every day. By looking at the x-ray with the veterinaries, he also understood their types of the injuries, from broken wings to bullet’s impacts. In Taipei, he searched for a similar place and discovered the Taipei Wild Bird Refuge, creating a link between the cities and a bridge for his research topics. In both cases, injured animals are delivered in cardboard boxes with holes, and the artist decided touse them as metaphors for the human interactions with birds in urban environments.

Robert Zhao Renhui, The Cacao Moth from Weidner’s collection,diasec in wooden frame 30x30cm, 2018.

Finally, in Hamburg, his encounter with Herbert Weidner constituted“the most pleasurable discovery” he ever had. Zhao had no prior knowledge of the scientist and was struck by the originality and by the scale of his collection. Weidner documented in details all possible impacts that insects might have on human daily life, collecting clothes, pieces of furniture, food, grains etc as evidence of their threat. In turn, Zhao photographed these artefacts in order to document the scientist’s vision of nature and his obsession to destroy all insects. Despite being a pioneer in addressing the issue of urban ecology,[29] Weidner’s work is not well-known, and the few articles pertaining to his collection are in German language. The only way for this encounter to happen was thus to physically engage with his collection, which largely contributed to the conception of the installation.

Zhao’s research practice is cumulative, and each artwork is nourished by the previous ones. His interest in insects, for instance, began with a fieldwork in California in 2015 when he worked with Dr. Martin Hauser, the Senior Insect Biosystematist at the California Department of Food and Agriculture. According to Zhao, the scientist opened his eyes about the invisible world of flies and their interactions with human life. His research led to the installation Flies Prefer Yellow (2015), but opened the path for more entomologic investigations. His works could be conceived as an open network that would grow under the umbrella of the ICZ, mirroring the nature interconnectedness and its fluid boundaries.

Artistic transformations of the research findings

Robert Zhao Renhui, When Worlds Collide, Installation View,Taipei Biennale, 2018.

Documenting the archives and designing stories

When Worlds Collide is a curated juxtaposition of the artist’s artistic documentation of his research findings. For The Birds of Athens, Zhao used the x-ray images from ANIMA and assembled them in one large photograph displayed in a light box. His series about Weidner, The More We Get Together (II), gathers his photographs from the scientist’s collection. Each image focuses on one single evidence of how insects destroy human objects, photographed on a plain and neutral background: chocolates eaten by moth, pieces of wood damaged by beetles, but also sample of pests classified according to their favorite food and crop’s destruction (rice, wheat,bark…). All photographs are framed similarly so as to constitute a consistent series. Finally, A Guide to the Fauna of Taiwan consists of photographs of stuffed invasive species shot in various science natural institutions in Taiwan, also edited on plain background. Zhao wishes to keep this neutrality in order not to be distracted by the context the animals are in. Most of them are seen from their back, which is their position in the museums’ window display, but which echoes the position of the injured bird’s skeletons. There is also a large photograph featuring the 52 frogs collected for the Taipei Zoo in one night. Zhao photographed them on site, on a whitebox, and edited the images later so that they appear all together on a white background as if it is represented a collection of the frogs’ identity photographs. Additionally, the artist created an installation with the empty cardboard boxes used by the volunteers to rescue the injured birds from the city, piled up in some corners of the room and in the center of the gallery. Some encircle a specimen of lizard, a brown anole, preserved in alcohol, caught by residents and kept at the Donghua University, Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Studies. On site, Zhao worked almost intuitively, trying to organize the works so that they can dialogue with each other.

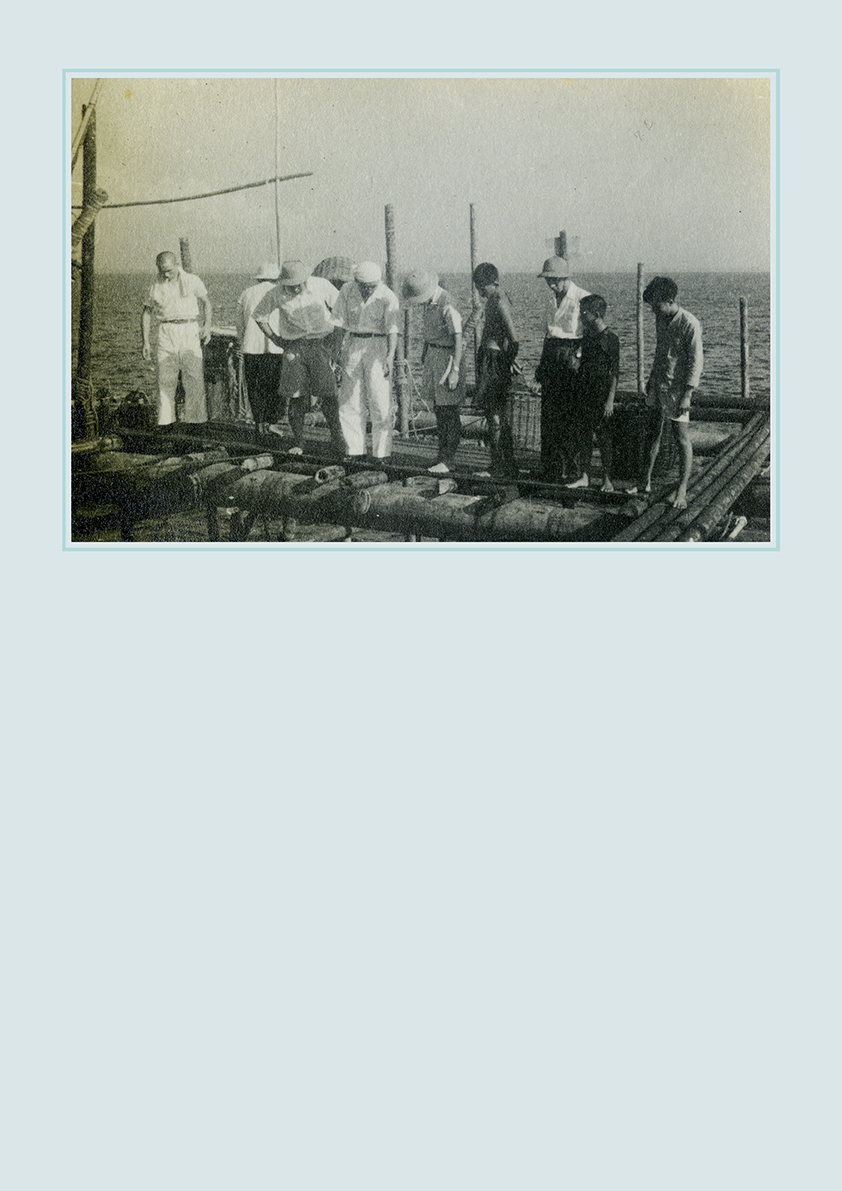

From his research outcome, Zhao therefore builds narratives that weave critically together these various stories in order to emphasize the ambivalence and complexities of the contemporary interactions between human and nature. The photographs, empty boxes and the curation of the installation support and embody these narratives that convey the idea of a nature that is alternatively destroyed and preserved, in all cases objectivized. He aims at staging the bodies of these non-human species in ways that scientists donot, in particular by highlighting the entanglement of human history with these specimens. There are no humans in the exhibition, though, except for one archival photographs of Taiwanese fishermen at the origin of a fish migration. Zhao so far never included any human in his photographs, for he feels there cannot be any right image that would feature humans and non-humans together. However, the human presence is felt everywhere, in a sort of negative space, while nature – real one if any, is totally and paradoxically, absent from the exhibition.

Curating an old-fashioned natural museum’s exhibition

Robert Zhao Renhui, Sacred ibis (Threskiornis aethiopicus), diasec in wooden frame 60x40cm, 2018.

An increased number of scholars from various fields demonstrate that the idea of nature as it has been constructed by modernity is no longer relevant to reflect on today’s reality. In particular, the divide between nature and culture has been deeply criticized while more inclusive and interdependent concepts have been developed in order to renew the relationships between humans and non-humans.[30] In this context, it is surprising to come across Zhao’s reproduction of natural museum displays to address contemporary interactions between humans and the natural world. Why referring again to this old and dusty model which is greatly embedded in the Western mode of thinking from the 19th century?

Perhaps especially because it seems now so far from today’s new conceptions of nature, this mode of representation stands out for its radicality and paradoxical perspective. Nature is in fact the great absent element of the exhibition, as one can only access it from representations of representations (images of objects destroyed by insects or the images of stuffed animals), except for the series of the invasive frogs, which are nevertheless dead subjects. As far as the empty boxes is concerned, they are precisely empty and what remains at best would be a trace of nature since they were used to carry the birds. This apparatus increases the distance that separates the viewer from these species and suggests it might be insurmountableand irreversible. We observe nature through a museum window, just like at the zoo, safely, while being totally separated from it.

While nature is changing and alive, what we are confronted with is the immobile image of death. Implicitly, the preservation of nature, and of native species, becomes a synonym of a frozen world, embodied by the anole specimen floating above its pedestal, at the center of the gallery. The species hung on the wall, often represented on their back, vulnerable, taken out from their environment and aligned the ones after another, look like miserable hunting trophies. Their passivity seems to refer to an invisible violence. The frail African sacred ibis, which symbolizes wisdom in Egypt, is for example all huddled and deprived of its majesty. From these positions of victims, some species nevertheless acquire a disturbing form of aura. The nearly 70 birds’transparent skeletons from The Birds of Athens seem for instance to glowin the dark, resembling sacred statues carved in religious places. Yet this mode of representation brings them back again in the past, in an in accessible world.

Robert Zhao Renhui, The Birds of Athens, x-ray photographs,210 x 140cm, 2018.

Mirroring the language of science and the museum’s display, the staging of the exhibition is neat, well organized, with species grouped according to their categories, all photographed according to a systematicmethodology. Order, classification, control… immediately comes back the modern idea of nature dating from the early 17th century in Europe, and its illusion that science would one day be able to completely reveal the secrets of nature. It brings forth a form of reductionism that consists in reducing nature to what can be scientifically observed, understood, and labelled in a box. As such, the installation points to the human unlimited desire for knowledge, thus for control, which seems to resist change.

Furthermore, the empty boxes could stand as metaphor of the superficiality that characterizes most human relationship with nature, especially when it comes to“save it.” There is an undeniable form of hypocrisy or blindness that the installation brings forth. All these boxes piled up everywhere suggest a form of bricolage, a lack of long-term policies and of mindset change: we only patch things up but continue to swat insects and to build glass buildings where birds crash. While specimens of insects are singled out because they eat corn, and as such are deemed as a threat, the same corn grows on lands redesigned and devasted by human monoculture. Choices are constantly made, at the expense of nature itself.

Robert Zhao Renhui, Wild Bird Society of Taipei – 14thDecember 2017, Daurian Redstart, Adult, Human Causes (Sticky Mouse Trap),Hsinchu. Cardboard box, 2018.

This staging seems to revive clichés and is almost caricatural. It functions as a provocation. During our conversations, Zhao proposed to switch off the commentaries from nature documentary in order to challenge scientific discourses. Similarly, what if we do not read his text and narratives? What could be learnt or understood from these isolated species, cut off from their origin and history? Not much. Invasive, native, injured species look the same, all equally mummified and denied as living creatures. What can we grab from a dead bird or from an x-ray of its injured wing? Can we imagine how it sings or breeds? Despite its title, the public cannot meet the fauna of Taiwan, but only its artificial and constructed image. Nature is elsewhere, outside. “Nature loves to hide” is a famous quote from Heraclitus.[31] The Greek knew already that there is mystery inside nature that probably no systematic scientific approach can grasp. The superb blue Magpie, printed in a larger format, might be the one who epitomizes at best nature’s elusive feature. The bird turns its back on the viewers and seems to ignore them completely. Its long and beautiful blue tail occupies the whole space and suits up the animal with a sumptuous feathered costume. While some birds are ridiculed because of their unnatural position, the magpie stands out for its dignity and mysterious magnificence, suggesting a resistance to any form of control.

Robert Zhao Renhui, A hybrid of the Chinese Blue Magpie (Urocissa erythroryncha) and Taiwan Blue Magpie (Urocissa caerulea), diasec in wooden frame 90x60 cm, 2018.

Anthropocentrism and politics

Zhao’s installation does not thus deal with nature, but with the human idea of nature. Preserving nature and native species or saving birds injured by human urban life are all human decisions and, so far, insects or birds have not their word to say. This idea of nature has evolved with time and differs from one culture to another.[32] In the exhibition, two different conceptions emerge: the scientific approach mentioned earlier (to know in order to control), and a romantic, yet political perspective according to which nature is an idealized form of order and harmony that humans need to reached back. Environmental historian Roderick Nash, who studied American wilderness, demonstrated how much the human idea of nature is ethical and political.[33] All politics of nature preservation imply the definition of an ideal state of nature that needs to be restored. This ideal, just like nature itself, is obviously a human construction. It implies that, throughout time, a chaotic state of the world has followed a state of harmony.

Robert Zhao Renhui, Stock Pests, diasec in wooden frame 30x30cm, 2018.

In the United States, some conservationists aim at returning to “an absolutely pristine pre-damage condition” of nature, which seems not only utopian but problematic, with the pending definition of the term “pristine.”[34] In many cases, defining such a state coincides with defining the origins of a nation, and its identity. What is native becomes what is national. In Singapore, for example, the building of the modern post-independence nation was associated with the building of a specific and tamed environment modelled on Switzerland.[35]The first post-independence Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew declared in 1968: “Wehave built. We have progressed. But there is no hallmark of our success more distinctive and more meaningful than achieving the position as the cleanest and greenest city in South-east Asia.”[36] The local preservation policies followed this objective and Lew Kuan Yew’s vision of a “tropical garden city,”[37] later redefined as“City in a Garden.”[38] In the exhibition, despite confronting invasive and so-called incontrollable species, the viewer cannot see all but order: every species keeps its right place, which is inside a closed box or frame. Does it mean that the implementation of nature preservation policies succeeded in taming the excess of nature and that the collision between the natural and the human worlds, even if sometimes brutal,leads inexorably to the return of order?

Beyond this anthropocentric and critical perspective, at the origin of Tim Morton’s concept of an “ecology without nature” that would precisely get rid of the narrow and anthropomorphic idea of nature,[39]the artist’s shift from nature to its confrontation with human conceptualization and handling of nature allows to approach today’s complex ecological issues from a wider scope.

Robert Zhao Renhui, Tilapia (A National Treasure), diasec in wooden frame 42x29.7cm, 2018.

Robert Zhao Renhui, Archival image from the artist’s own collection, diasec in wooden frame 42x29.7cm, 2018.

Reflecting on the current ecological crisis as it is addressed by a few contemporary artists, art historian T.J. Demos warns about the risk of remaining superficially focus on the present and of neglecting the roots of this state of emergency. Just like Bruno Latour who insists on the interdependence of fields,[40] he invites us to situate the current ecological issues in a broader context, involving its historical, cultural, social and political dimensions.[41] Although his work mainly focuses on recent practices, Zhao precisely invites us to consider each species, and its current state, as a result of a longer history that involves interacting with human behaviours, policies and culture. We learn for example that the presence of today’s most common fish in Singapore, the tilapia, is a product of Japanese war efforts and of smuggling activities between Singapore and Taiwan. Each species can be approached from this renewed viewpoint that mirror human history and, beyond, its identity and construction. These interdependent networks and connections, which are at the core of the installation, have nevertheless not really found their visual and artistic embodiment: they remain in a discursive form and are only suggested, in this case, by the artist’s juxtaposition of an archival image featuring Taiwanese fishermen, from the artist’s own collection, and a photograph of one tilapia. Paradoxically, and more generally, while the works emphasize the effects of global migrations and flux, there is a lack of dynamism and fluidity in their modes of representation.

Finally, and politically, it would be tempting to push the metaphor of invasive species and removal policies to individuals, colonial and racial politics, with indigenous populations or migrants deemed as threat for certain“native” populations in order to justify politics of exclusion, yet this is not directly suggested by Zhao’s work.

Conclusion

When Worlds Collide documents artistically Zhao’s fieldwork in Hamburg, Athens and Taiwan and various cases of collisions between the natural and the human worlds. The artist’s practice mainly consists in reframing and re-contextualizing the archival material he found during his research fieldwork, and in building narratives that weave these various stories altogether. The work focuses on mutual acts of destruction as recorded by humans yet brings back a larger contextual framework within which such complex and often ambivalent relationships have been modeled.

The discursive part of the work, printed in a leaflet given to the public, plays an essential role in conveying these narratives, since this historical perspective, in particular, cannot be directly intuited from the works. The viewing experience, for its part, directly confronts the audience with today’s contradictory discourses about nature. The old model of the natural museum offers here a relevant framework to underline the staggering gaps that maintain human and non-human species in separate spheres. All documentary photographs are conceived to strengthen the isolation of each species and point to their denaturalization. Objectified, they look deprived of their essence and autonomy, and ceased to represent living creatures. When confronted to human’s will and desire of control, they do not have their word to say. Such radical representations challenge the prevalence of the constructed idea of nature when it comes to any ecological policies, and the human possibility to interfere with natural processes.

Hence, despite increased critical posthuman and ecological discourses that demonstrated the necessity to think beyond the human and non-human divide, the installation highlights how much this idea remainssalient and expresses itself in our urban daily lives. Zhao shows us a society deprived of nature which runs after a lost yet ideal natural paradise. What collide are not only the natural and the human worlds, but a modern conception of nature with its contemporary conceptualization, ecology and the idea of nature, politics and nature, beliefs and reality.

[1] The11th Taipei Biennial, entitled Post-Nature—A Museum as an Ecosystem, was curated by Mali Wu and Francesco Manacorda (Nov. 2018- Mar.2019).

[2] The mission is defined on the website of the Institute: https://www.criticalzoologists.org/mission/mission.html

[3]This article is based on the author’s interview with the artist in Singapore in May 2019 and on various e-mail exchanges taking place during the summer 2020. The artist’s quotes come from these conversations.

[4]Mack et al., “Biotic invasions: causes, epidemiology, global consequences and control,” Ecological Applications 10(3) 2000:689.

[5]Ko-Huan Lee et al., “A check list and population trends of invasive amphibians and reptiles in Taiwan,” Zookeys 829: 86, 2019.

[6]More details of all the Taiwanese invasive species, see Ko-Huan Lee et al., “Acheck list and population trends of invasive amphibians and reptiles inTaiwan,” Zookeys 829: 85-130, 2019.

[7]“Chiayi offers incentives to encourage killing of invasive lizards,” Focus Taiwan journal online, Sept 07, 2016. (https://focustaiwan.tw/society/201609070013).Some universities are also involving their students in what has been called“The Dino Hunters.” See Taipei Times “Former pet iguanas become nuisance around Kaohsiung” by Jonathan Chin, Apr. 16, 2016.

[8]Chang I-chen and Sherry Hsiao, Taipei Times “County calls on public to report invasive frogs” Apr.26 2018

(https://www.taipeitimes.com/News/taiwan/archives/2018/04/26/2003692028)

[9] Chen Kuan-pei and William Hetherington “Sacred ibis nest control ineffective: environmentalist” Taipei Time, Mar. 21, 2018.(https://www.taipeitimes.com/News/taiwan/archives/2018/03/21/2003689734)

[10]“Although we do not have evidence on the threats to native ecosystems in the wild, human agriculture might be seriously damaged from adult iguanas which are able to wipe out the entire crops from the field within a few days” in: Ko-HuanLee et al., “A check list and population trends of invasive amphibians and reptiles in Taiwan,” Zookeys 829: 102, 2019.

[11] In studying the case of the Puerto Rican frog, English environmental journalist Fred Pearce emphasizes the complexity of defining the status of a species. See Pearce Fred, “The strange case of the Puerto Rican Frog,” Anthropocene Magazine, October 2016. Available at https://www.anthropocenemagazine.org/2016/10/the-strange-case-of-the-puerto-rican-frog/

[12]From the ICZ’s website: https://www.criticalzoologists.org/worlds/index.html

[13]Christmas Island, Naturally (2015). Seehttps://www.criticalzoologists.org/christmas/index.html

[14]Fred Pearce defines these novel ecosystems as “systems composed of new combinations of native species and species introduced by humans, but where the system itself does not depend on humans to keep it going.” Pearce Fred, “The strange case of the Puerto Rican Frog,” Anthropocene Magazine, October2016. Available at https://www.anthropocenemagazine.org/2016/10/the-strange-case-of-the-puerto-rican-frog/

[15]The ‘New Wild” is the title of Fred Pearce’s 2015 book: The New Wild: Why Invasive Species Will Be Nature's Salvation.

[16]Allison Stuart, “The Paradox of Invasive Species in Ecological Restoration,”in: Invasive and Introduced Plants and Animals: Human Perceptions, Attitudes and Approaches to Management, edited by Ian D. Rotherham, Taylor and Francis Group, 2011, 268.

[17]The researcher, who introduced what became urban ecology, created four categories of insects: ‘Insects that destroy Food’, ‘Insects that destroy Wood’, ‘Insects that Destroy our Materials’ and ‘Insects that causes harm to People.’

[18]The collection belongs to the Zoological Museum Hamburg (now part of the Centrum für Naturkunde) where Dr. Herbert worked as a curator.

[19]The idea of Garden City was conceptualized by former prime minister Lew KuanYew. See for example Chan Lena, “Nature in the City,” in Planning Singapore:the Experimental City edited by B. Yuen and S. Hamnett, London and NY,Routledge, 2019.

[20]“24 chickens and roosters roaming around Sin Ming Avenue were euthanised after residents in the area complained they were too noisy.” See Feb 2017 newspaper article https://mustsharenews.com/endangered-chickens-singapore/

[21]See the website where trees are registered: https://exploretrees.sg/ In fact, most of the fauna and flora is protected by laws and registered. See Heng Lye Lin, “A Fine City in a Garden – Environmental Law and Governance in Singapore,” Singapore Journal of Legal Studies, 2008: 106.

[22]Stock Marybeth, “Robert Zhao Renhui and Teamlab: Glass Rotunda at National Museum of Singapore,” Art Asia Pacific Jan 06, 2017. Available at:

http://artasiapacific.com/Blog/RobertZhaoRenhuiAndTeamLabGlassRotundaAtNationalMuseumOfSingapore

[23] Inorder to build a consistent narrative that would connect all the displayed elements from The Nature Museum, Zhao invented for instance the figure of naturalist Francis Leow and included the Leow archives in his installation. A description of the guided tour and exhibition can be found in Yee Marcus,“The Nature Museum,” Art Asia Pacific Magazine Available at:

http://artasiapacific.com/Magazine/WebExclusives/TheNatureMuseum?fbclid=IwAR3suOz0_05CeJXE_ETwQmJXZPynW6LJU8XbvwyGrgJ_NwZSpaoJwVStQ4w

[24]See the case study dedicated to Anggawan Kusno’s artwork and the artist’s website https://www.tanahruncuk.org

[25] In 2011, some of Zhao’s photographs of camouflage insects were accepted in the scientific magazine Discovery. They originated in the series “The Great Pretenders” (2009), a study of Phylliidae, or leaf insects. The story can be read in http://artasiapacific.com/Magazine/88/RobertZhaoRenhui.

[26] In Athens, in 2017, Zhao was invited by the Fast Forward Festival to create aspecific installation responding to the city’s stories about nature; in Hamburg, in 2018, the artist took part in a research residency funded by the Goethe-Institut Singapore and worked from the entomology collection from the Zoological Museum in Centrum für Naturkunde (CeNak); in Taipei, in 2018, he was invited by the Taipei Biennial to produce a new work dealing with the curators’ theme of Post-Nature—A Museum as an Ecosystem.

[27]Fred Pearce. The New Wild: Why Invasive Species Will Be Nature's Salvation. Beacon Press, 2015; Ian D. Rotherham. Invasive and Introduced Plants and Animals. Routledge 2013; Tao Orion, Beyond the War on Invasive Species:A Permaculture Approach to Ecosystem Restoration, Chelsea Green Publishing 2015; Masanobu Fukuoka. The one-straw revolution: an introduction to natural farming. Rodale Press,1978.

[28]More on ANIMA, see their website: https://www.wild-anima.gr/en/

[29]British zoologist and animal ecologist Charles Elton is more recognized as the pioneer of invasive ecology. See in particular his 1958 book The Ecology of Invasions by Animals and Plants.

[30]See for instance work and concepts by Philippe Descola, Donna Haraway, BrunoLatour, Tim Morton…

[31]Heraclitus’s fragment 123 quoted in Graham Daniel, “Does Nature Love to Hide?Heraclitus B123 DK,” Classical Philology vol 98, number 2, April 2003.

[32]For a history of the idea of nature in the East, see for example Collingwood, Robin George. The Idea of Nature. Oxford University Press, Incorporated,1960.

[33]Nash, Roderick Frazier. The Rights of Nature: A History of Environmental Ethics. University of Wisconsin Press, 1989.

[34]Allison Stuart, “The Paradox of Invasive Species in Ecological Restoration,”in: Invasive and Introduced Plants and Animals: Human Perceptions, Attitudes and Approaches to Management, edited by Ian D. Rotherham, Taylor andFrancis Group, 2011, 273.

[35]Heng Lye Lin, “A Fine City in a Garden – Environmental Law and Governance in Singapore,” Singapore Journal of Legal Studies, 2008:104.

[36]Quoted in Heng Lye Lin, “A Fine City in a Garden – Environmental Law and Governance in Singapore,” Singapore Journal of Legal Studies, 2008:68.

[37]Lee, K.Y. From Third World to First: The Singapore Story, 1965–2000: Memoirs of Lee Kuan Yew. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish, 2000.

[38]Chan Lena, “Nature in the City,” in Planning Singapore: the Experimental City edited by B. Yuen and S. Hamnett, London and NY, Routledge, 2019, 117.

[39]Morton Timothy, Ecology Without Nature: Rethinking Environmental Aesthetics.Harvard University Press, 2009.

[40]See in particular Latour Bruno, We Have Never Been Modern, trans. Porter Catherine, Harvard University Press, 1993.

[41]Demos T.J. “Extinction Rebellions,” Afterimage, Vol. 47, Number 3, pp14–20, 2020.