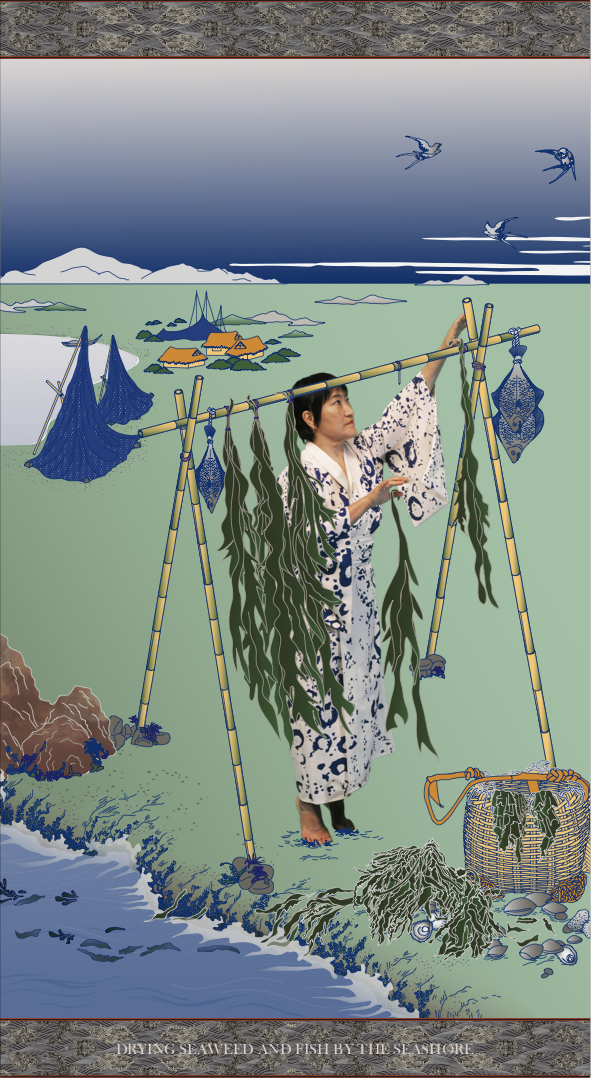

The artists at work, modifying and painting over archival photograph from the colonial era.

Courtesy of the artist

“The Name” (2008 - ) by Burmese artists couple Wah Nu and Tun Win Aung is probably the first research-based artwork from Myanmar. Based on modified archival photographs, this sound and image installation features 33 portraits of important Burmese figures who lived between the first Anglo-Burmese War (1824-1826) and the independence of the country (1948). Forthis series, Wah Nu & Aung delved into the colonial past of Myanmar, searching back all the “heroes” that fought against the British and whose memory has been either erased or sullied: against the British account of history, and against the instrumentalization of these figures by the successive authoritative governments, the Burmese couple aims at emphasizing the acts of resistance that constitute Myanmar collective memory.

So far, the series has been exhibited three times, in Yangon (2015), Singapore (2016), and Hong Kong(2018).[1] In the installation, the human-size images are projected in a loop and accompanied by a monotonous voice-over enumerating the names of about 700 Burmese people who fought against the British, for the independence of the country.

Since the artist do not exhibit their research findings, the work is far from being didactic and rather generates a sensuous and empirical knowledge: the sound installation, with the loud voice over, creates an almost mystical experience where the Burmese heroes look like eternal ghosts.

Contextual framework and artists’ drive

Against the British humiliation of Burma

The British colonization of Myanmar (Burma at that time) lasted from 1824 to 1948, when the country became independent. It followed three successive stages and main conflicts that cumulated in 1885 with the annexation of Upper Burma and the creation of Burma as a Province of British India.

During the colonization process, and during the colonial rule, the country felt deeply humiliated. Burma was not even a colony on its own but a province of India: “rarely was Burma viewed by its imperial masters as anything other than a marginal colonial possession, and never did it wholly erase the stigma of the fateful decision to make it an appendage of British India.”[2]In “The British Humiliation of Burma”, Terrence Blackburn notes that “at thetime, Burma was called “the Rice Bowl of Asia, so great was its production, and trade in this staple was mostly in the hands of British merchants.”[3]Maurice Collis, who served in Burma as a British officer, concludes his memoirsby confessing that the British, including him, “had done two things, which we ought not to have done. In spite of declarations to the contrary we have placed English interests first, and we had treated the Burmans not as fellow creatures, but as inferior beings.”[4]

This humiliation could be epitomized by the British relationship with the king. On 29 November 1885, when the British troops entered Mandalay, the royal capital of the Burmese empire,they sent the royal family in exile within the following 24 hours and transformed the palace into a gentleman’s club, auctioning without any respect all the royal furniture, including the sacred throne.

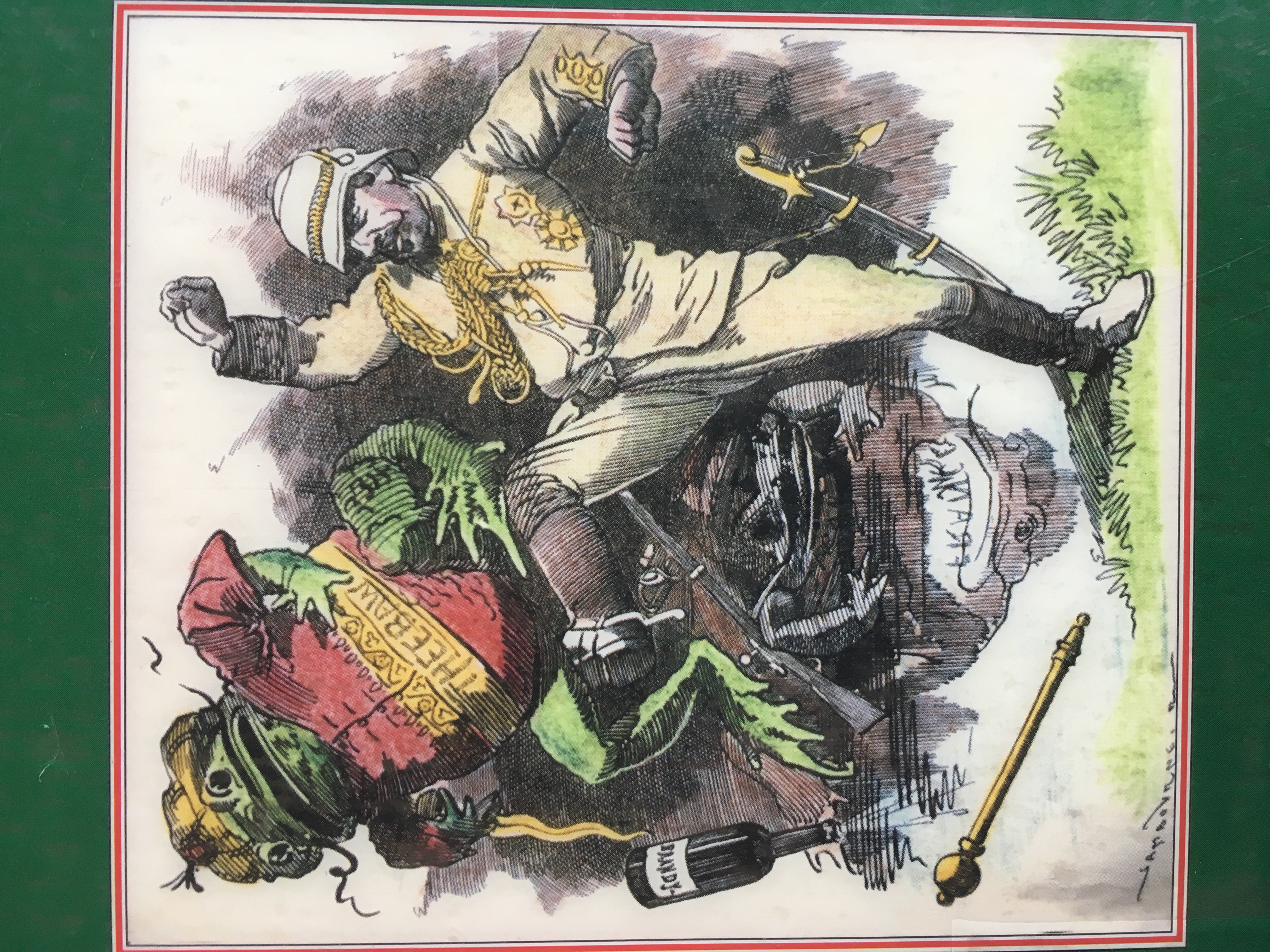

“The Burmese Toad”: General Prendergast shown kicking the reputedly drunken King Thibaw out of his kingdom. Another toad, symbolizing France, watches in the background. An engraving fromPunch, 31 October 1885 (courtesy of Noel F. Singer).

This engraving comes from a British comic magazine published shortly before the final invasion of Mandalay. It features king Thibaw, represented under the form of a toad, kicked out by an English soldier. Under the hit, he is letting down a bottle of brandy and hisroyal sceptre.[5]Many European writers described him as a drinker, a fool or a cruel king.[6]

King Thibaw and the QueenSupayalat. Archival image from the Palace Museum, courtesy of the artist.

In contrast, in this above archival photograph, the king and the queen stand proudly in their royal palace, dressed in their coronation costume. The artists found it on a Burmese history book, but they told me they also saw it at the Palace Museum in Mandalay. From these two opposite representations of the king it is easy to understand how biased an image can be, according to where it comes from and to whom it is addressed. Accordingto the artists, king Thibaw was not an alcoholic and only the Europeans liked to depict him this way.

Scarcity of local archivalmaterial

In fact, in Myanmar, most of the archival material and much of what has been written about the colonial period originatesin British sources, therefore was documented from the British perspective. In the colonizers’ records,in particular, most of the Burmese people who oppose the British rule were called thieves or “dacoit,” and were accused of banditry.[7]Many were jailed or hung for these reasons. At that time, there were no historical accounts from the Burmese side since history has been taught for the first time under the British, with English textbooks praising Britain as the mother of Burmese.[8]As far as photographic documents are concerned, only foreigners were taking photographs,[9]and the country was either represented through stereotype exotic sceneries that pleased foreigners, or through the images of the “dacoits” taken by the officers fighting them.

From the 1920s onward, a nationalist movement developed, including strong critiques about the way the British were teaching history.[10]Burmese historians started to write their own accounts of the past, referring back to ancient chronicles of past glorious achievements.[11] However, these historians were often favoring patriotism over historical accuracy.[12] Myanmar has been ruled by the military since General Ne Win’s coup in 1962 and “has endured relative and even absolute decline” since then.[13]During these decades of military rule, the local representation of the colonial period has been constantly nourishing nationalism and xenophobia, rather than being the object of truly academic research.[14]Today, the country is thus only, and very slowly, recovering from 60 years of dictatorship with a violent repression on freedom of speech and limited civil rights. In 2008, at the beginning of the project, it was very difficult to conduct scholarly research in the country.[15]Myanmar has slowly opened since 2011, but scholarly history books written by Burmese historians for Burmese people are still scarce. Most of the scholars are still foreigners and either expatriate Burmese or Burmese who studied abroad.[16]

Considering the ongoing political instability and today’s difficult state of transition, it is easy to understand that, for Burmese people, there has been little space to build a consistent post-colonial discourse and to achieve a post-independence national identity, even if these questions have been at the core of many political debates. It is in this context that Wah Nu and Aung wish now to reclaim the colonial past from a Burmese viewpoint:

“Now it is the time for those who have appeared in the pages of history books as thugs, thieves and robbers to be given back the true account of their lives. They were not dangerous people as claimed by the history books written by the victors, but rather they were the ones whose lives were endangered.”[17]

The artists’ research

Working as “historians”

“The Name” started in 2008 when the artists read Nehru’s book “The Discovery of India” (1946): Nehru wrote it when he was in jail, imagining and praising India as a sovereign nation, in homage also to the Indian heroes who fought for its independence from the British. This reading pushed Wah Nu and Aung to go ahead with a similar process. They have also been deeply influenced by ’s 1983 book “[18][19]’sthroughout historyBy modifying existing archival images – mostly old reproductions from British history books – they aim at giving back dignity to these figures and at rebuilding Burmese collective memory.

Based in Yangon, Myanmar, Wah Nu (b.1977) and Aung (b.1975) are both graduated from the Yangon University of Culture, Wah Nu in music and Aung in sculpture. Both have then developed other artistic mediums including painting, video and performances, exploring in particular theissues of memory, history and the current socio-economic situation of their native country. It seems that the artists have not been influenced by anyone before engaging themselves in research, but it is notable that Wah Nu comes from a family of film directors and intellectuals. Aung is also teaching at the Yangon University. For personal reasons, he is passionate about collecting books and magazines, a habit that he shares with other Burmese artists: under the military rules, media used to be strictly controlled by the state and while the country was totally isolated from the rest of the world,[20] artists tried to catch up with all possible alternative sources, collecting foreign magazines such as Time, Newsweek or Life Magazine. When they began the project, Aung started to collect images from historical books, and soon realized that they were very scarce in regard to the number of names that they found from British records.This is with this particular set of mind and personal taste that the artists engaged deeply in their research process.

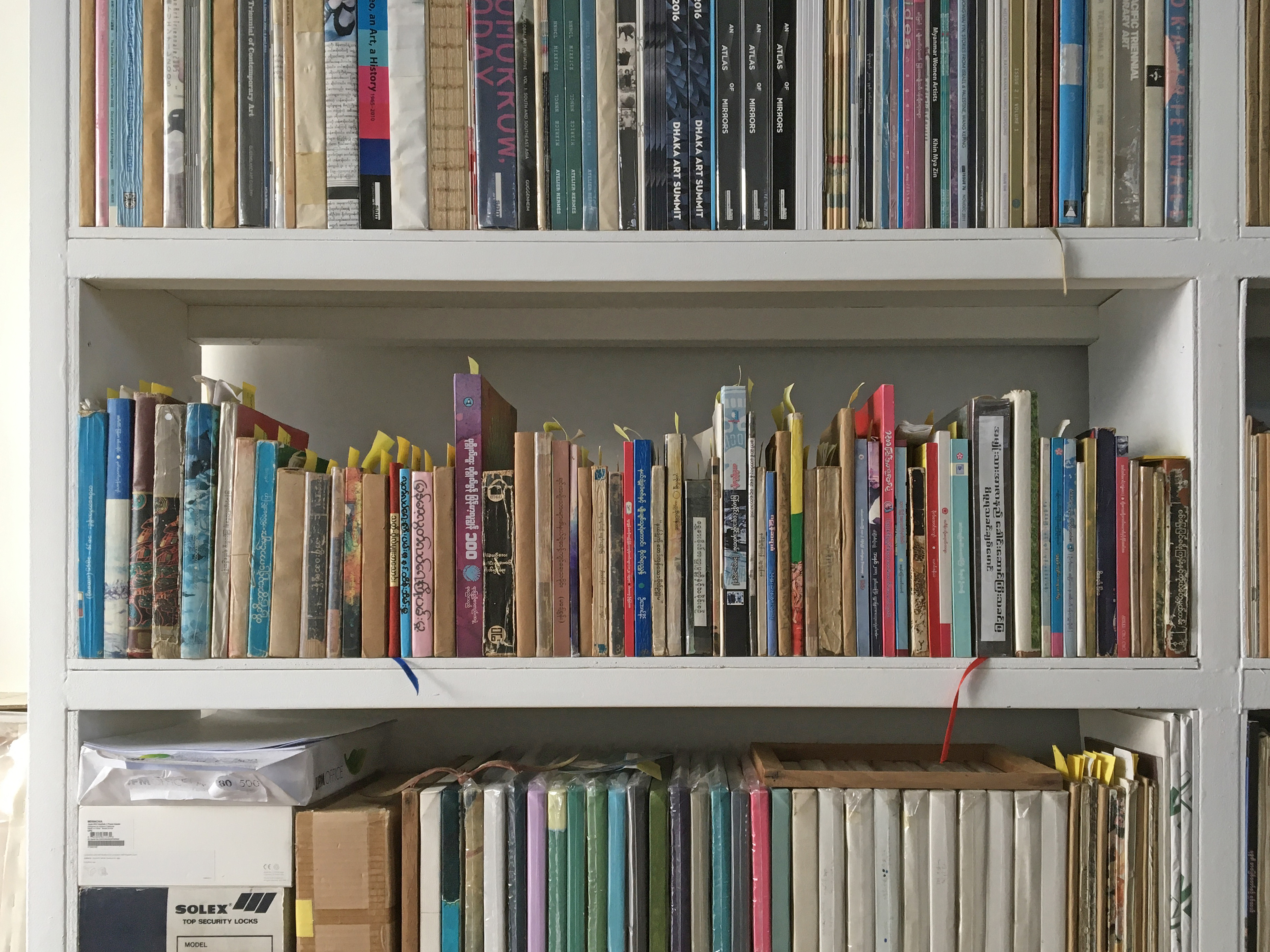

Artists’ references books for “The Name” in their studio. Courtesy of the artists.

Wah Nu and Aung do not claim to work as historians but rather originally combine their artistic process with some methodologies of work of the historian. In order to give credibility to their argument, they borrow their research tools from the academic field of history, reconsidering facts, excavating archives and comparing them. According to their findings, and against the dominant British account of Burmese colonial history, they propose a renewed vision of history.

From the beginning, the artists restricted their research to the colonial era, from 1824 to 1945, and defined very clear criteria for the selection of the featured figures. These figures,man or woman from that time who opposed the British colonization, must have been under what the artists call “mudslinging”, that is whose names have been insulted throughout history. We have already seen the example of King Thibawand how the British denigrated his memory. Besides, the chosen figures should not have been rewarded for their engagement into the resistance against the British nor use their experience to make politics. Most of them, if not killed, had a very ordinary life afterwards. This is why, as the artists explained tome, former Prime Minister U Nu from the first post-independence civilian government is not included in the series: even though he fought on the side of General Aung San, his later political position worked as a reward for his commitment. Similarly, King Mindon, who preceded King Thibaw on the throne, is not part of the selection either because “he could stand on his own in history: he communicated with the British as the king and was known internationally as such.” Finally, there is a less defined idea about the moral quality of these figures, judged, in a way, as “good persons” from the artists’ point of view.

Identifying the “heroes”

For each figure, the starting point of the research is usually an archival photograph found in a history book or in a magazine. Once they find a relevant image, the artists try to identify all the persons involved, looking for their names but also for details of their biography. Then, they search for other sources to confirm the identification.

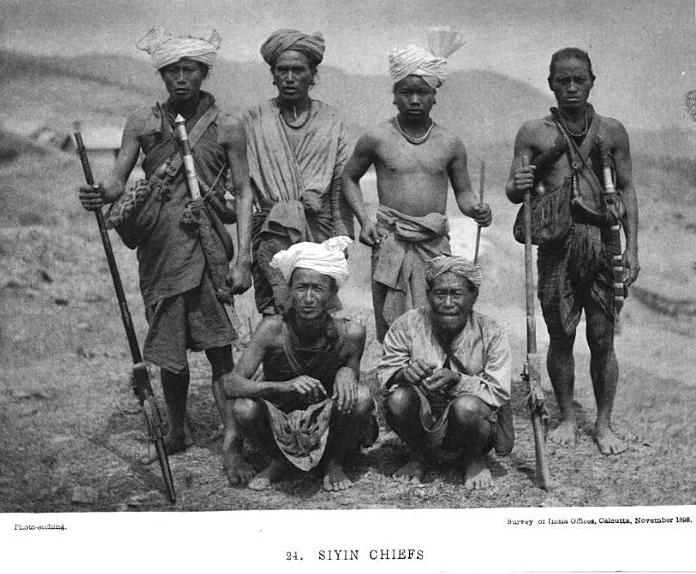

“Siyin Chiefs,” from Carey Bertram Sausmarez (1896) The Chin Hills: a history of our people, Rangoon,Printed by the superintendent, government printing , Burma.

This black and white illustration represents a group of six Siyin Chin people pausing in the countryside, probably close to their village that can be seen afar. On the upper left, the artists believed having identified Bu Khai Kham, a Chin leader who led a rebellion against the British after they took the Chin Hills territory. Unsuccessful in his revolt, he was arrested and sentenced to a life imprisonment on the Andaman Islands in the Indian Ocean, but returned to the Chin region in 1910. The caption says ‘Siyin Chiefs’ (the Siyins arepart of the Chin ethnic group), and it has been taken shortly after the annexation of their territory. The original photo comes from “The Chin Hills”,a book published in 1896 in Yangon and written by a British officer, Bertram S.Carey.[21]It has also been reproduced later in Myint’s book “Burma’s Struggle Against British Imperialism,”[22]and this is where the artists probably discovered it. From this first identification, the artists searched additional sources where the Chin rebel would be depicted or represented. They finally found an engraving that is standing at the entrance of a village named after him. Erected in 1979, this engraving says that Khai Kam fought in 1886 “for the liberty of his people andlove of his motherland” and he is represented standing and holding his rifle.

Khai Kam engraving at theentrance of the Khai Kam Village. Photograph courtesy of the artist.

Additional research helps them also to learn more about the figures, revealing some details about their life that can be added on the representation: type of weapon used, social status, specific attributes such as hat or costume, occupation in the civil life etc. WahNu and Aung found his portrait on another Burmese history book, featuring the Chin leader holding his long rifle and sword. While they might hesitate about the authenticity of some sources, they find more certitude by crossing them and by comparing their content. The artists eventually combined all these different images to create their own representation of the rebel.

Portraits of Kai Kam from the Burmese original version of Myint Ni Ni, Burma’s Struggle Against British Imperialism (1885-1895) (Rangoon: Universities Press, 1983). Courtesy of the artist.

The artists are working from all possible sources, both scholar and non-scholar, in order to locate these key figures and to learn about their stories. From the British records of that time,there are lists of names of those who were arrested, jailed and hung. This is an important source for the artists, but these lists usually bear no other details. Wah Nu and Aung also buy books on e-Bay, collect oral stories, contact booksellers and collectors. They found some interviews in magazines where people remembered the pre-independence period, so they also combine microstories with macro-stories to try to get as close as possible to their subject. Until recently, it was difficult to find books in the country, especially foreign books. When the artists refer to Burmese sources, they actually sometimes refer to British books translated or published in Myanmar: since, again, most of the original sources are British, the Burmese literature on the subject comes from these primary sources. The images are then reproductions of reproductions. Now the artists are also increasingly using Internet to compare their sources and conduct deeper investigations.

From the existing archives and British records, Wah Nu and Aung managed so far to identify 33 key figures from this period, whose portraits compose the work. They also found 700 other names, enumerated in the voice-over of the installation: for these men and women, the artists are still searching images to create their portraits. There are actually thousands of people who gave their lives for the independence, but there are no records about them, and they will probably never be remembered.

“We do believe that this work will be an important resource of art to a certain extent in the history of Myanmar. For this reason, we are taking a great care in analyzing the information. The chosen ones for this artwork did sacrifice themselves with all their efforts, both physically and mentally, in fighting for the country’s independence. They gave their mighty lives for what they believed. In frank, they were in wars for the future peace but took no reward back for themselves.This fact is important. After independence, many got the rewards for the loss of blood and sweat in the colony era. We do not count them for our artwork. Most of them in this work are the forgotten and ordinary ones, not the well-knowns. To them, this is a sincere tribute. As they were the people with difficult trace, few images and facts, we have to keep the findings and materials private. This means an attempt of saving their names in history from the passing times.”[23]

No documentation on display

Wah Nu and Aung are very precise in their methodology of work, and they claim being very cautious when it comes to trusting a source. However, and contrary to historians, they do not systematically document their process of research. When they started the project, they did not have yet a clear idea of the scope of the work they wished to produce and did not engage in such a documentation process. Therefore, it is not currently possible to access all their research materials, spread in their studio or perhaps lost.

Furthermore, Wah Nu and Aung do not share with the public their pieces of evidence and research findings. When theseries was exhibited at the Singapore Biennale in 2016, there was no text about the featured figures, and the work was only accompanied by the artists’statement. The artists are now thinking of adding short biographies of the 33 figures, in order to help the audience to know more about each person, but they will not display their documentation as they do not wish to. In the above interview they said they request to “keep the findings and materials private” in respect for the figures they are studying. Hence, the viewers are asked to trust the artists about their research process, and about what they assert to be true. This might be ambiguous because, obviously, history can always be approached from various perspectives. For instance, by wishing to find evidence against the British’s point of view, and to empower the Burmese side, Wah Nu and Aung might disregard some of the sources that do not fit their goal, even unconsciously.

In history, even though there is room for interpretation, there is still an idea of truth: from solid sources, one can say with confidence that the British entered Mandalay and pushed out King Thibaw from his palace on November 29, 1885. There is little chance that this sort of facts will be questioned in the future, even though the possibility remains open, as it is always with past events. However, it is hard to tell if the king was really an alcoholic or if some rebels like KhaiKam were really fighting for independence or were also thieves. Some rebels might have been both. Blackburn argues that “in the beginning their motives were indeed noble, but soon these roving bands found it more lucrative to roband commit the most gruesome atrocities on their own defenceless people.”[24] Collis, who was in Burma inthe 1920s, explains what could have later cause the confusion between the fighters for independence and bandits: on his account, encouraged by thegeneral chaos, some ex-convicts and other violent persons took this opportunity to commit acts of crime and banditry.[25]For his part, Thant Myint-U acknowledges that, in there bellions’ period, “there was brutality on both side.”[26]

What matters the most, thus, is probably not the accuracy of the artist’s research but the process of research itself and the transformation of their findings into an artistic artform. The renewed vision of history they propose, and its credibility, are indeed not only based on their findings but also on their aesthetic choices, strongly supported by their references to traditional symbolism and local systems of beliefs.

Artistictransformations of the research findings

Modifying the archives

“The Name” can be perceived as a palimpsest with interwoven layers and meanings: Wah Nu and Aung interpret,re-appropriate, decontextualize and reconstruct the images from the past, driven by their desire to give back dignity to these forgotten or mistreated heroes. To do so, they draw on traditional and local iconographic and symbolic elements of the Burmese culture, transforming the original archival images into potential mythological representations.

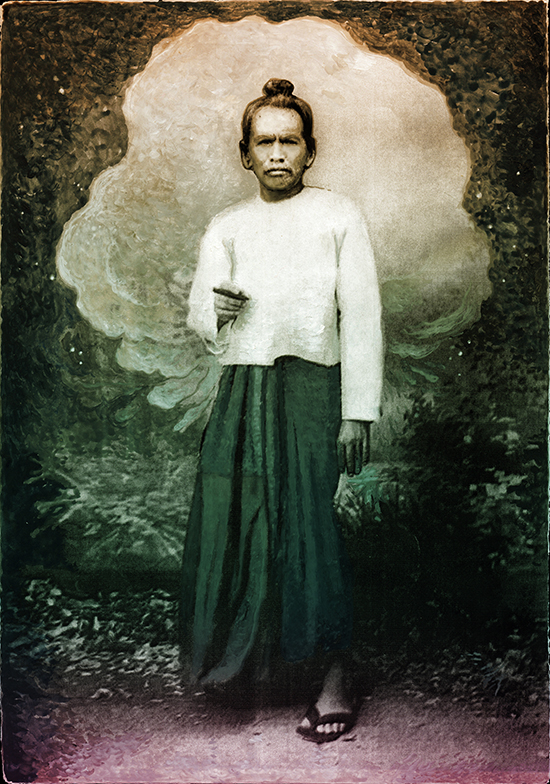

Every image is treated according to a similar process of work. The archival found image is first modified on computer before being printed on a A4 format. The artists paint on this layer and photograph the outcome in a very high resolution so that the final image could be printed or projected on a human size format.

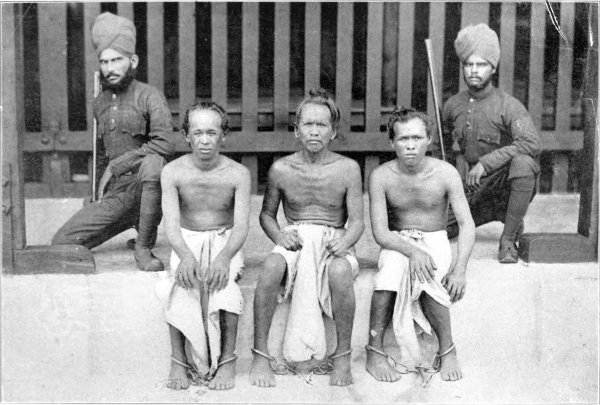

“Bo Cho, the robber and histwo sons,” in White Thirkel H., A Civil Servant in Burma (London: Edward Arnold, 1913)

This archival image belongs to an illustrated English-language book written by a civil servant, Thirkel White, who worked in Burma for about thirty years from 1878 and who wrote his personal memoirs. It features Bo Cho and his two sons before their hanging by the British. The three men are represented bare-chested in white sarongs, sitting in the middle of the image and fettered with foot cuffs. Their gaze is fierce and stern as they stare at the photographer. Two armed Indian guards surround them. The author relates that Bo Cho was said to command seven hundred men, “a leader of a formidable gang”, and depicts how he was finally arrested as he went back to the jungle, with his two sons.[27]

In contrast, in Wah Nu and Aung’s artistic portrait below, we contemplate a village chief looking at us with dignity and pride, a position he held for some time. For the artists, Bo Cho is not a robber but an honourable revolutionary. From the archival image,they only kept his face and imagined how he would have been dressed in his chief village costume.

Bo Cho, from “The Name”(2008 - ) by Wah Nu and Aung. Courtesy of the artists

In fact, the 33 human-size figures are all represented standing, usually looking straight into the eyes of the public with pride. The whole series is also very consistent in terms of colour and lighting: the black and white tones from the original archival images are still visible, as the artists painted on the top on them with only pale colours, so that the images still look like ancient photographs. The figures are very bright as if they were radiating from the inside. The background is usually very simple, slightly blurry, only filled with painted plants or clouds encircling the head and the body of the figure. Furthermore, the artists included small fittings and details that refer to the specific life of the depicted men and women. At the back of their representation of King Thibaw, for example, one can see the Royal Palace and both the moon and the sun as symbols of his royalty. Other accessories allow to identify chief villages from farmers or villagers. Some of these additional references are not easy to catch for non-Burmese people unfamiliar with the local culture. For instance, Garuda (Galone in Burmese language) is drawn at the back of U Chit Pu, one of the fighters who serve dunder the army of Thu Panaka Galone Saya San, which led a famous rebellion in the 1930s. A Hindu and Buddhist deity, and a figure linked to royal authority, it is a mighty mythological bird very popular in Myanmar. There are also more subtle references that might be harder to decipher for the general public, such as the presence of a turtle on the side of Thakinma Ma Thein Tin. In Burmese language, and according to the artist, the term ‘shell’ is very close to the term ‘tax’, and this lady led a revolt against the British, encouraging people to refuse to pay tax. There is thus a pun that can be understood only people familiar with her biography.

King Thibaw, from “TheName” (2008 - ) by Wah Nu and Aung. Courtesy of the artists

Re-interpreting the past: the language of art

This re-contextualization allows the artists to offer up a new way to understand the past, revealing what has been hitherto concealed or forgotten. This renewed vision of history is strengthened by strong artistic choices: each portrait is highly aesthetic and beautiful. The small and vivid brush strokes of paint impart an enigmatic atmosphere to the work, while giving a sense of dynamics to the composition. The figures look alive, borne by this vibrant background and bright staging. Both brushstrokes and pixels from the photographs are visible and sometimes overlap: time seems to be frozen, and the figures look eternal. From this perspective, the artists are freely creative, and the research does not seem to interfere with their choices. They rather use the art language to empower their subjects. In their representation of Khai Kam, for instance, the Chin leader, known as being as strong as fivemen, is surrounded by long white strokes of light, tearing vertically the sky apart, just like a super heroes.[28]Some fighters are also shown with their weapons hung behind them, as if they were in the middle of ablazon. As for General Aung San, he is represented surrounded by a white cloud,which, according to the artists, stands as a metaphor for power and for struggle.

Khai Kam from “The Name” (2008 - )by Wah Nu and Aung. Original version on a A4 format. Courtesy of the artists

Khai Kam from “The Name” (2008 - )by Wah Nu and Aung. Human-size projection. Courtesy of the artists

The presence of this large and white cloud in many portraits might suggest that “The Name” is more a work of devotion than a work of mere representation. This pictorial element does not produce any specific knowledge per se about who these people were, but rather embodies the aura that the artists try to re-establish.

General Aung San from “The Name” (2008 - )by Wah Nu and Aung. Courtesy of the artists

In every culture, clouds are associated with celestial spheres: they connect the earth with the sky and represent the fusion of elements, water and air, earth and heaven. Clouds are also directly hinting at the Buddhist pictorial and traditional representation of gods. In Ranard’s book Burmese Painting, there is an illustration of a celestial figure painted in Abeyadana Temple in Pagan in the late 11thcentury, showing a woman flying on a cloud, or springing from the clouds whose pattern is similar to the pattern used by the artists.[29] Pagan was the former capital of the first Burmese empire, and the temples of Pagan have continuously inspired artists over time, including contemporary ones.[30] In Buddhism iconography there are often flying apsaras or Bosatsu on clouds, and these analogies invite the viewer to draw a comparison between the portrayed figures and gods. For some of the figures,this deification is already part of their history: the King, of course, who was regarded as“an incipient Buddha”[31],Saya San who proclaimed himself King and even “Setkya-Min, the Burmese equivalent of the chakkavatti or universal emperor” (Adas, 1979),[32] and even General Aung San, considered as a“larger-than-life hero.”[33]Suzanne Prager demonstrated that his political actions fit the career of animminent so-called ‘future king’ (minlaung) in the Burmese beliefs.[34]

Reactivating collective mythologies

The dramatization of “The Name” is finally strengthened by the voice-over, which works like an incantation.The names of the 700 Burmese who fought against the British and who have been identified by the artists are indeed enumerated by amasculine voice in a loop, in a very formal and ceremonial way. Originally, the artists added a piece of music but changed their mind in order not to distract the focus of the viewer. This monotonous voice pervades the space and surroundsin turn the figures with its own sacred dimension, adding to the aura of these people.

The staging of the 33 figures reminds us indeed of the painted portraits of leaders from the past as they can be contemplated on the walls of palaces or temples. Everything seems to have been activated by the artists in order to represent them as heroes:their use of symbols, aesthetic, and the dramatic staging of their body cannot be perceived as realistic and objective. The exact truth about who they were does not seem to matter anymore, as they become the subjects of a kind of devotion. Furthermore, during the projection, the figures are classified according to alphabetic order, and there is no chronology. This strengthens the idea that they are all part of the same body, which is a symbolic and apolitical body. As such, the artists seem to create aspiritual and eternal body that would personify the power of resistance and that would constitute the foundations of a Burmese collective memory. Therefore, and paradoxically, the knowledge generated by the series does not so much stem from the research conducted by the artists about each figure but from the powerful and emotional aura that pervades the installation as a whole. Here, we leave the realm of reality to enter the realm of rituals, constructed collective memory and commemorations.

Conclusion

With “The Name,” Wah Nu and Aung are contesting the colonial interpretation of history and the Burmese official knowledge framework as it has been inherited from the British. They also compensated for the scarcity of scholarly works on the subject caused by the recent decades of repression and violence that left very few opportunities for historical research. Against the domination of British accounts of the colonial period, and against the general political socio-historical production of narratives, created to satisfy political agenda, the artists’research process seeks to fill gaps in local knowledge and to renew the foundations of the Burmese collective memory. Wah Nu and Aung use research as astrategy to counter this vision of history and to propose their own, based on their research findings. While they do not claim to be historians, they emphasize the research dimension of their practice in order to give credibility to their project. At the same time, they do not display their archival records and found documents: the stress is put on the artists’ process of work that seems to suffice to justify their claim. In fact, this apparent contradiction embodies the strength and originality of the work. “The Name” is at the same time grounded in the real, generated by a rational apparatus, and rooted in beliefs thus exposed to any intuitive and personal responses. This open approach adds to its credibility as it opposes the authoritative system of knowledge production and allows for a trust-based relationship to emerge between the public and the artists. Confronted to the artwork and its aesthetic and immersive experience, the viewer remains indeed active in his personal (re)connection to this proposed collective memory, which remains far from any institution and freed from any political propaganda.

For an in-depth analysis of the series, see Ha Thuc Caroline “Research as Strategy: reactivating mythologies and building a collective memory in Wah Nu and Tun WinAung’s The Name,” Journal of Burma Studies Vol.23, No1, 2019.

[1]Building Histories, a group exhibition curated by Iola Lenzi at the Goethe Institut,Feb.-March 2015; Singapore Biennale 2016, An Atlas of Mirrors,Oct.2016-Feb.2017; Documenting Myanmar, a group exhibition I curated atCharbon Art Space March 2018.

[2]Holliday Ian, Burma Redux (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2011), 26.

[3] Blackburn R.Terrence, The British Humiliation of Burma (Bangkok: Orchid Press,2000), 140.

[4]Collis Maurice, Trials in Burma (London: Faber Finds, 1938), 216.

[5] The detailed of the engraving is “The Burmese Toad”: General Prendergast shown kicking the reputedly drunken King Thibaw out of his kingdom. Another toad, symbolizing France, watches in the background. An engraving from Punch, 31October 1885 (courtesy of Noel F. Singer) The image has been reproduced on the cover of the book “The British Humiliation of Burma” by Terence R. Blackburn(2000) Orchid Press Bangkok.

[6] See Aung, Htin. The Stricken Peacock: Anglo-Burmese Relations 1752–1948, (The Hague: M. Nijoff,1965); Webb, George. “Kipling’s Burma, an Address to the Royal Society for Asian Affairs.” The Kipling Society, June 16, 1983. http://www.kiplingsociety.co.uk/rg_webb_burma.htm.

[7] See, for example,the 1931 British report on rebellion (East India Burma rebellion 1931: 349).

[8]Salem-Gervaisand Metro, “A Textbook Case of Nation-Building: The Evolution of History Curricula in Myanmar,” The Journal of Burma Studies 15, no. 1 (2012):31.

[9] Interview with Lukas Birk, archivist and curator of the exhibition Burmese Photographers, organized at the Goethe Institute in Yangon Feb. 18 to March 11 2018.

[10]Salem-Gervais Nicolas, “École et construction nationaledans l’Union de Myanmar” (Schooling and Nation-building in the Union of Myanmar)” (PhD diss., INALCO Paris, 2013), 68-69.

[11] Sarkisyanz, Emmanuel. “Messianic Folk-Buddhism as Ideology of Peasant Revolts in Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century Burma.” Review of Religious Research 10, no. 1 (1968): 32-38.

[12] See Aung-Thwin Maitrii, “Structuring Revolt: Communities of Interpretation in the Historiography of the Saya San Rebellion,” Journal of Southeast AsianStudies 39, no. 2 (2008): 303; Salem-Gervais and Metro, “A Textbook Case of Nation-Building: The Evolution of History Curricula in Myanmar,”Ibid., 33; Geertz Clifford, The Interpretation of Culture (New York: Basic Books, [1973] 2017), 305.

[13]HollidayIan, Burma Redux, Hong Kong University Press, 2001:1

[14]Jacques Leider, head of the Bangkok-based Ecole Françaisede l’Extrême-Orient (EFEO) and a well-known advisor to the Myanmar military’s Armed Forces Historical Museum in Naypyidaw, email interview with the author. March 2018

[15] Gravers Mikael,“Spiritual Politics, Political Religion, and Religious Freedom in Burma.” The Review of Faith & International Affairs 11, no. 2 (2013): 47.

[16]Maitrii Aung-Thwin did his PhD in the United States and lives in Singapore; Thant Myint-U was born in New York city and educated at Harvard and Cambridge Universities; Dr. Maung Maung was educated abroad; Htin Aung was educated at Oxford and Cambridge…

[17] Artists’statement, Singapore Biennale 2016 An Atlas of Mirrors.

[18] Myint Ni Ni Burma’s Struggle Against British Imperialism (1885-1895) (Rangoon: UniversitiesPress, 1983).

[19] In the preface of the book, Emmanuel Sarkisyanz notes that “Daw Ni Ni Myint’s work is practically the first detailed, documented monograph about the Burmese resistance to the British conquest of 1885-1886 in Upper Burma and the very first presentation of the ensuing guerrilla warfare in Lower Burma.” Sarkisyanz Emmanuel,“Preface,” in Burma’s Struggle against British Imperialism (1885–1895),ed. Ni Ni Myint (Rangoon: Universities Press, 1983), i-vi.

[20] See Kean Thomas,“Public Discourse” in Routledge Handbook of Contemporary Myanmar, editedby Adam Simpson, et al., (London: Routledge, 2017).

[21]Carey Bertram Sausmarez, The Chin Hills: A History of Our People. (Rangoon: Superintendent Government Printing, 1896).

[22]Myint NiNi, Burma’s Struggle Against British Imperialism (1885-1895) (Rangoon: Universities Press, 1983),

[23]Wah Nu and Aung, unpublished interview by Chu Yuan from the Singapore Art Museum at the occasion of the Singapore Biennale 2016 An Atlas of Mirrors (courtesyof the artists)

[24] Blackburn R. Terrence, The British Humiliation of Burma (Bangkok: Orchid Press,2000), 111.

[25] Collis Maurice, Trials in Burma (London: Faber Finds, 1938), 214.

[26]Myint-U,The River of Lost Footsteps, (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux,[2006] 2008), 29.

[27]White Thirkel H., A Civil Servant in Burma (London: Edward Arnold, 1913), 260.

[28] Carey Bertram Sausmarez, The Chin Hills: A History of Our People. (Rangoon:Superintendent Government Printing, 1896).

[29]Ranard Andrew, Burmese Painting (Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books, 2009), 2.

[30] For example, see Htein Linn and the motif of the dancers that comes from a mural of one of the temples in Pagan

[31]Leach Edmund, “Frontiers of Burma,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 3, no. 1 (1960): 57.

[32]Adas Michael, Prophets of Rebellion: Millenarian Protest Movements against the European Colonial Order (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1979).

[33]Naw Angelene, Aung San and the Struggle for Burmese Independence (ChiangMai: Silkworm, 2001).

[34]Prager Susanne,“The Coming of the ‘Future King’” The Journal of Burma Studies 8 (2003):1–32.