Timoteus Anggawan Kusno: the Centre for Tanah Runcuk Studies (2013 - ) and the Rampog Macan Javanese rituals

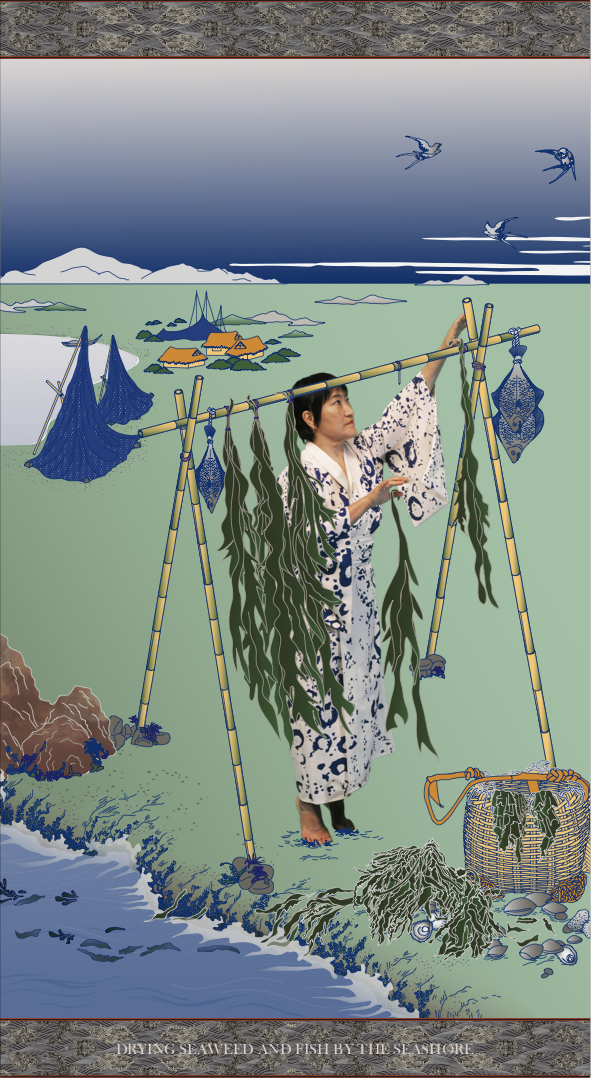

The Untold Stories ofArchipelago,2017

View of the exhibition Power and Other Things: Indonesia & Art (1835-now) curated by Charles Esche and Riksa Afiaty. Centre for Fine Arts Brussels (Bozar), Belgium.2017.

Courtesy of Centre for Tanah Runcuk Studies and the artist.

In 2013, Indonesianartist Timoteus Anggawan Kusno (b.1989) created the Centre for Tanah Runcuk Studies (CTRS), an imaginary research institution that focuses on Tanah Runcuk ,a fictional territory located in the “East Indies,” an explicit reference to the Dutch colonization of Indonesia. The CTRS gathers artistic - but also actual - archival material from the colonial period (drawings, paintings, photographs, artefacts etc.) as well as documents and texts written by real and fictional scholars.[1]

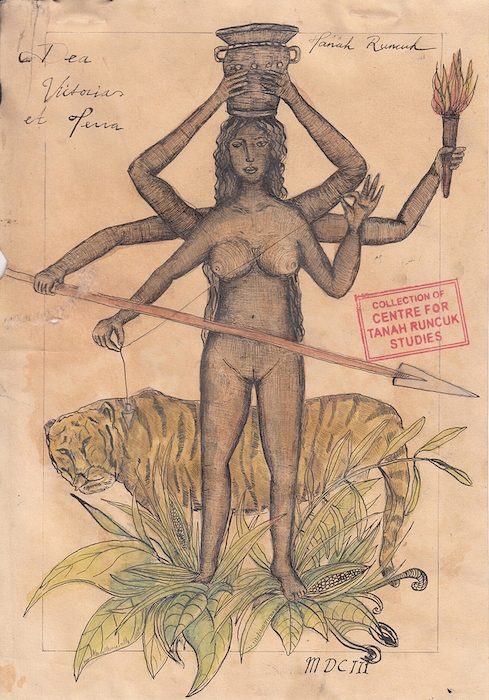

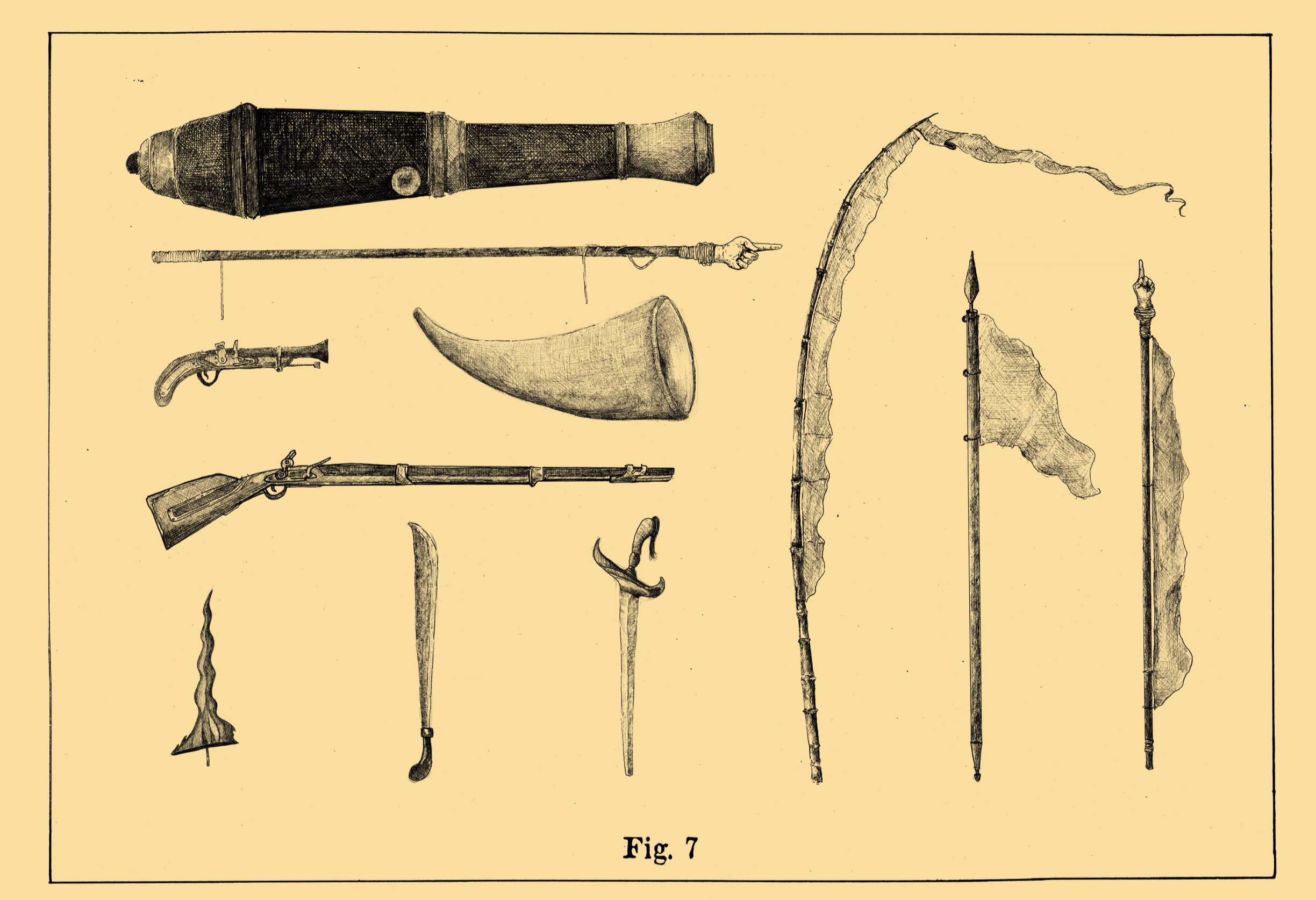

Memoir of Tanah Runcuk: A Note From The “Lost” Land (2014), the first exhibition organized under the umbrella of the CTRS, was presented like an ethnographic museum show with all the artworks displayed in showcases, labelled and described with scientific and Latin terms.[2] Drawings from Tanah Runcuk’s fauna and flora were for instance juxtaposed with sketches featuring the local people’s customs, weapons and deity. As the artist’s research findings expand,the Centre simultaneously grows and most of Kusno’s artworks develop consistency within this framework. Still diverting the language of ethnography,The Untold Stories of Archipelago (2017), exhibited in Brussels, Belgium, was curated as if all the works belonged to a 17th century Western cabinet of curiosity.[3] In parallel, Kusno also created performances from more specific topics pertaining to the colonial past. The Death of a Tiger (2017), notably, originates in the artist’s investigation on traditional and colonial Javanese rituals, whose ideology still imbues today’s Indonesian society.

Kusno presents himself as an artist drawn by his academic background who works with ethnographic methods and institutional approaches. He graduated in social and political science at the Gadjah Mada University in Yogyakarta and his research practice embraces the fields of history, ethnography and museology. His engagement in research responds to the specific post-colonial and post-dictatorship context of Indonesia: by questioning historical truth and historiography through there-activation and falsification of archives, it aims at shedding light on hidden or neglected facts of history that still haunt today’s society. As such,the artist’s practice challenges today’s legacy of the European model of knowledge production and distribution, and opens the path toward a critical and plural perception of Indonesian history.[4]

Contextual framework and artist’s drive

Against a centralized meta-narrative of the national history

After the Portuguese traders, the Dutch reached the archipelago in the 16th century and founded the Dutch East India Company (VOC) in 1602. When the company went bankrupt in 1800, the colony became nationalized.[5] The colonial regime revolved mainly around trade, aiming above all at making as much profit as possible,[6] yet it involved repression and violence. The process has been summarized by a repetitive pattern: “peaceful contact, growing mistrust and finally violent conflict.”[7] Jan Pieterszoon Coen(1587-1629), an officer of the VOC who founded Batavia as the capital of the Dutch East Indies, could embody such colonial violence for its bloody conquest of the Banda Islands and the exploitation of its local resources. During the colonial times, many resistance movements opposed the Dutch authority and somewell-known national heroes and charismatic leaders stood out, especially duringthe Java War (1825-1830).[8]

Golden Bust (inspiredby Jan Pieterszoon Coen’s portrait)2017

Courtesy of Centre for Tanah Runcuk Studies and the artist.

Most of the reports and archival material of that period of history originate in Dutch or British officers’ testimonies and were produced in order to serve colonial interests. However, unlike in Myanmar,[9] there have been an increasing number of historical studies written from an Indonesian perspective. Many leaders of resistance movements such as Dipanagara, Surapati and Sultan Agung, depicted as villains in Dutch history books, were turned into national heroes,[10] although often in order to serve national identity building. Great local historians such a Sartono Kartodirdjo(1921-2007) or Ong Hok Ham (1933-2007) have studied the colonial power. In fact, “since the fall of Suharto, re-writing and re-imagining Indonesian history has topped the agenda for many historians of Indonesia.”[11]

Despite this vast endeavor, Farah Wardani, the former executive director of Indonesian Visual Art Archive (IVAA),[12] underlines the lack of local infrastructure dedicated to archives and recalls that the primary archives have been collected by the colonial powers, and are therefore located in Europe.[13] Most of them are written in Dutch language and, for Indonesian people, these archives are thus still difficult to access. Furthermore, according to the artist, a large part of the existing archival material remains “untouched” by scholars and stored or hidden in depots rather than being publicly accessible. For him, “these archives are in ‘locked down’ and ‘sleep mode’. They need to be awakened, resurrected, reread, and put back into today’s context and debates.”[14] His concern for archives coincides with an increased interest in archives and the awareness of their paramount importance in the country and especially in Yogyakarta, where the artist works and lives, since the 2000s. IVAA was created there in 2006 and an active community of artists is delving into archival material and national historiography.[15]

The construction of a single historical narrative is not an exclusive colonial prerogative. While the independence from the Netherlands was self-proclaimed in 1945 and officially gained in 1949, the writing of history seems to have remained an instrument for legitimating the power of the successive rulers in their post-colonial processes of nation-building. Quoting Indonesia scholar Ariel Heryanto, Gerkeand Evers note, in particular, that “in Indonesia, since independence, the social sciences have almost totally been in the service of whatever government was in power.”[16] The education system and school text books usually served as well the State political agenda, especially during Suharto’s New Order authoritarian regime (1966-1998) when there was one single official national history.[17]

However, according to the Indonesian historian Agus Suwignyo, the New Order regime is not the only one to blame for the writing of a complacent and centralized meta-narrative of the national history: while Suharto reduced and probably falsified some parts of history in order to legitimize its power, this self-centered conception of Indonesian history originates in early years of nationalism. For him, this“Indonesia-centric-historiography” emerged from the nationalist movements that rose against a “so-called Neerlando-centric-historiography” and aimed at correcting the way history was hitherto written, namely from the colonizers’sole perspective. This political and nationalist tool, however, reproduced thestate-centered approach of the Dutch” and a top-down perspective.[18]

In this context, and beyond any form of dichotomy that merely opposes a colonial from a nationalist perspective, Kusno’s own approach of history aims at bringing forth a plurality of voices and points of view. By mixing real and artistic archives, he wishes to expand our vision of history from a more critical angle.

Against historical ignorance

Dea Victoria Et Terra,Drawing Studies - Societas Tanaruncia Circa 1603. (Collection of Centre for Tanah Runcuk Studies).

Courtesy Timoteus Anggawan Kusno, Centre for Tanah Runcuk Studies

Today, with Internet,most Indonesian people can access national history and confront their findings with Google and Wikipedia. Indonesian institutions and the education system are also adapting themselves to the recent processes of modernization and democratization. However, according to the artist, the access to education and,thus, to historical knowledge, remains unequal.[19]

Besides, since the1990s, there is a trend that tends to simplify history, nurturing a form of nostalgia and of fascination towards colonial times. Against today’s backdrop of insecurity, poverty and instability, this period begins to appear as abetter time for some Indonesian and as “an escape from present-day hardship.”[20] The trend is present in both the public and private spheres, favoring tourism and design, inspiring movies and styles. It is known as tempo doeloe (a longing for the “Good Old Days”of the Dutch East Indies) and mooi indie (the beautiful Indies). Yet Kusno wonders for whom these days could be remembered as good, and which colonial past could be desired today? For him, there is irony in imagining the past by ignoring what has been left unseen. “What if we were imagining and romanticizing the wrong side of history?”[21] These over-simplifications of the past call thus for a more in-depth, pluralistic and more nuanced approachof history.

Even though Kusno’sapproach of history is artistic, his sources and references are always clearly mentioned so that the public can go further in learning about the colonial events he is referring to.

Colonial and Feudal Specters

Map of Rampokan Siluman Macan in Tanah Runcuk painted by unknown artist (collection of Centre for Tanah Runcuk Studies)

Courtesy Timoteus Anggawan Kusno, Centre for Tanah Runcuk Studies

In fact, beyond the colonial past, what is really at stake in Kusno’s practice is the legacy of this past and how it is still molding today’s Indonesia. From the centralization of the power in Java to the law and legal system, scholars have pointed to the institutional continuity that links the colony to the independent state.[22] The sense of national unity arose as well from the identification of a common oppressor, namely the colonial rulers, contributing to the building of a national identity and of national discourses.[23] For Kusno, two decades after the fall of the New Order regime, these specters still haunt every level of society: “we may find them hiding behind what we take for granted in our daily lives, in things that are institutionalized and that construct us, in the mystification of the single version of history, in how a memorial makes us remember this and not that, in how "us" and "them" are defined, in what we can and cannot talk about.”[24] In particular, colonialism has been built upon and entwined with former forms of feudalism that were revivedduring the New Order regime and that continue to permeate the society.

While the CTRS addresses all these entangled issues and heritage, The Death of a Tiger and the recent artist’s research focus on a specific type of Javanese rituals which could embody a systematic legitimation of violence at work during thecolonial times and until today.

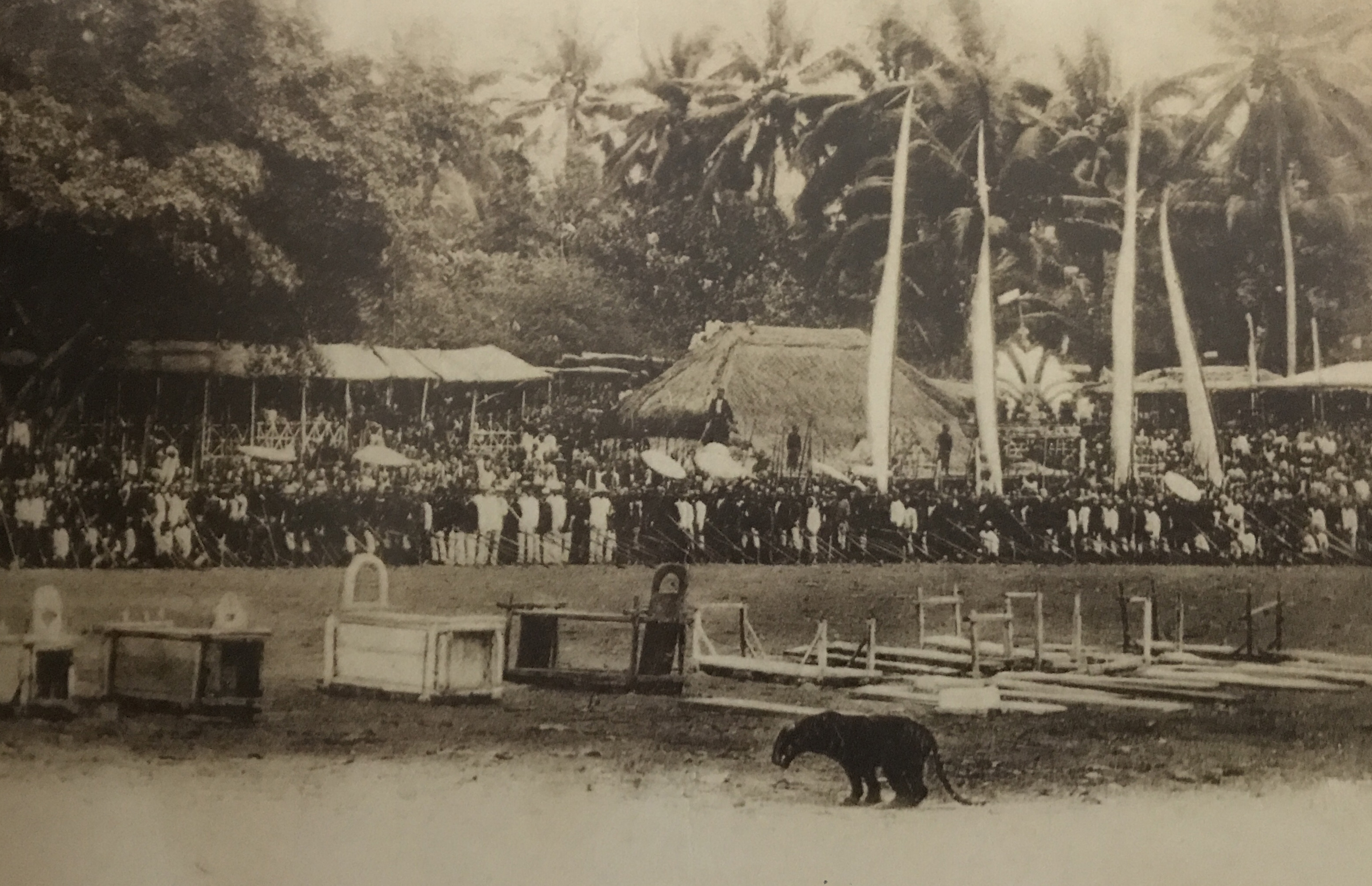

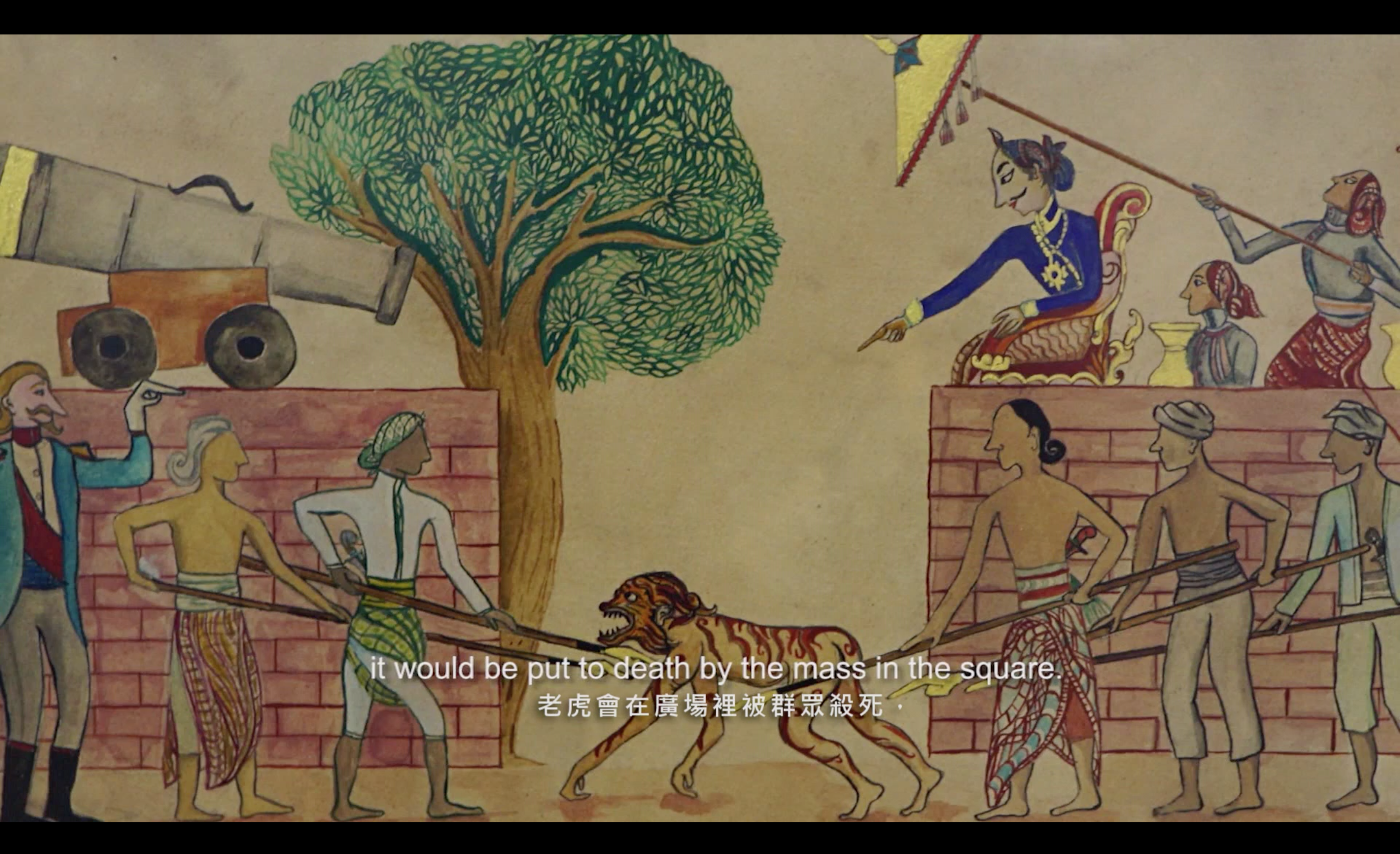

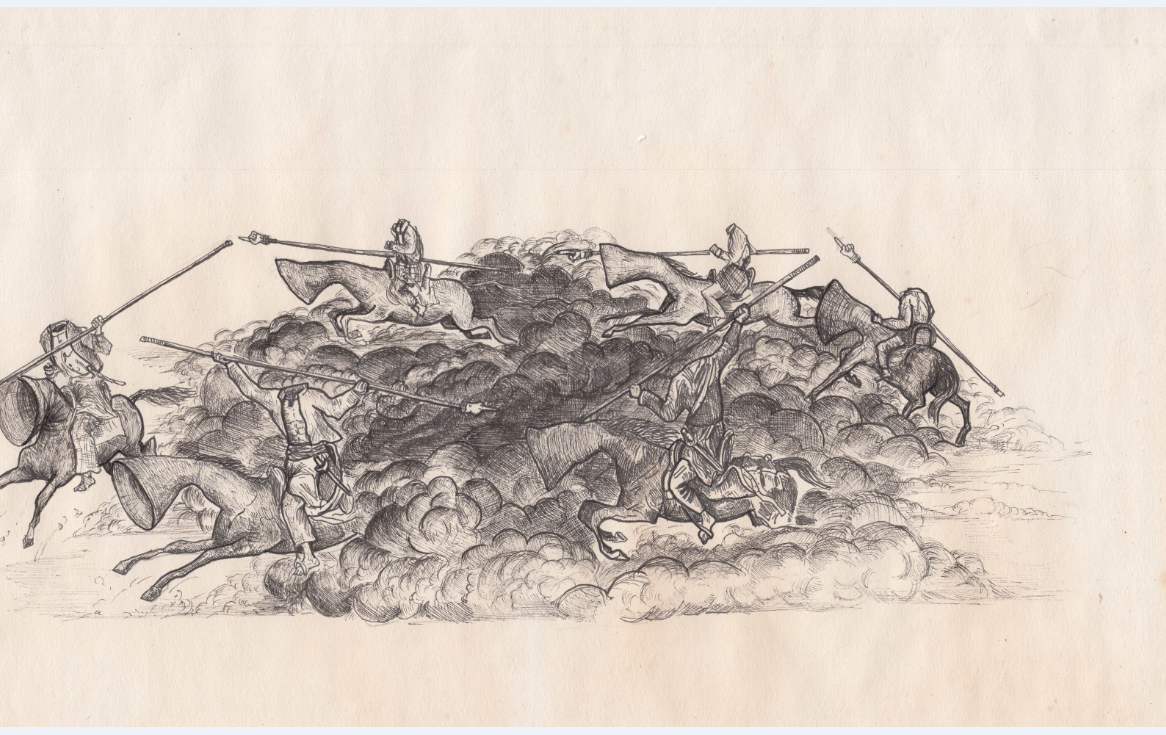

The Rampok Macan rituals (macan means tigers in Javanese language) took place mostly in Java as early as 1605 and lasted until 1906.[25] During these state-sponsored ceremonies, a tiger was killed publicly in a large square near the king’spalace, surrounded by three or four rows of spearmen. Usually there were two consecutive fights: a tiger-buffalo followed by a tiger-sticking where the tiger that survives the first fight had to fight again. The tigers were exhibited in cages in the royal courtyard as a demonstration of power, against rivals but also against nature at large.

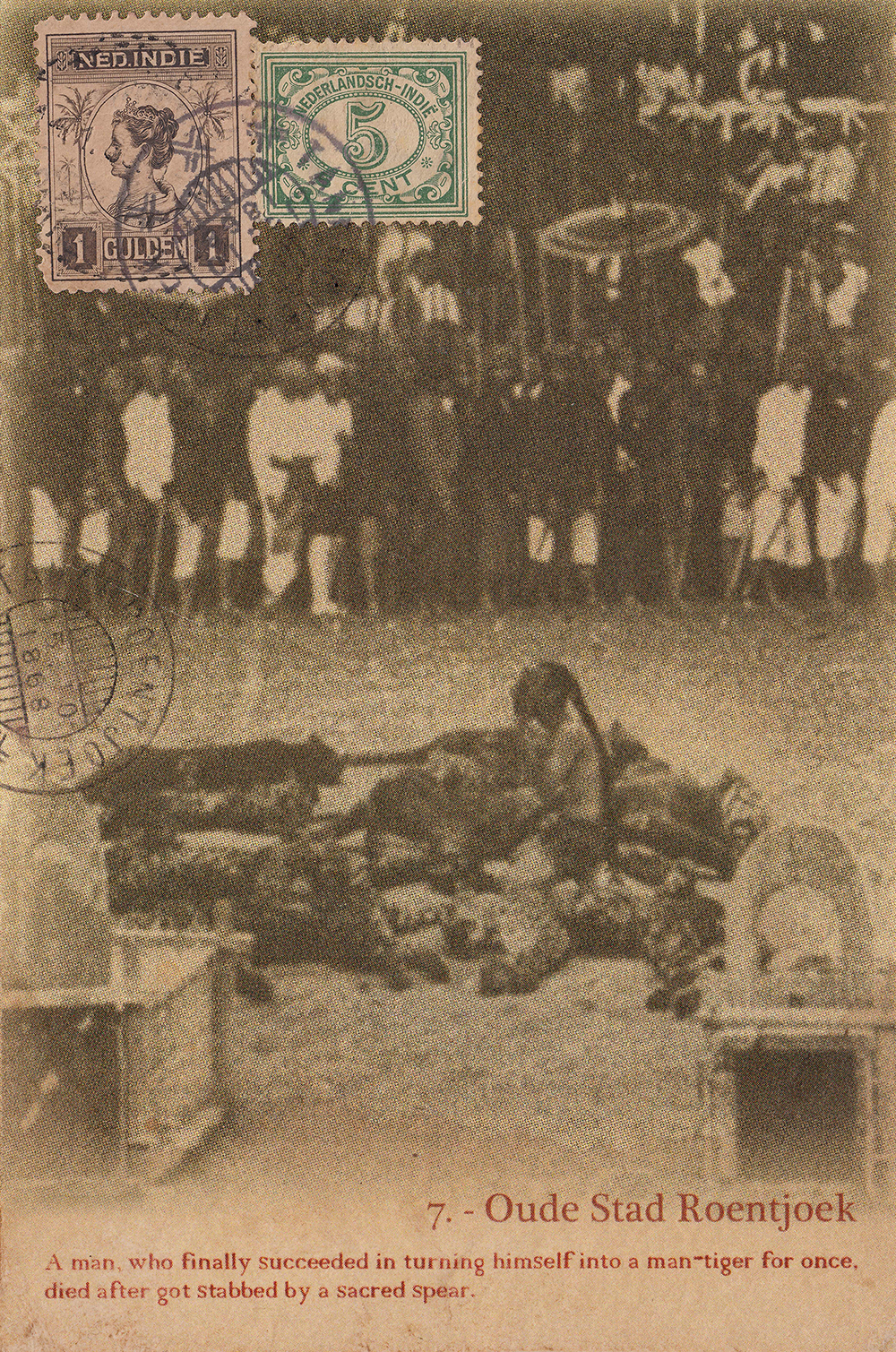

Oude Stad Roentjoek, Postcard Reproduction,2018.

Print on archival paper, aluminum dibond, 330x500mm

Courtesy Timoteus Anggawan Kusno, Centre for Tanah Runcuk Studies.

Dutch historian Peter Boomgaard notes that the rituals multiplied between 1830 and 1870, contributing to the extinction of the local tigers. This period coincides with the Dutch imposition of the Cultivation System that implied an intensification of the exploitation of resources and labor, leading to famine and poverty among the Indonesian people.[26] In that context, the Dutch re-appropriated the rituals to boost their own authority. The ceremonies were introduced in new places, where the colonials ‘invented’ these traditions, and “degenerated into entertainment for European visitors.”[27]

These rituals disappeared at the beginning of the 20th century, but what remainsis a form of institutionalized legitimation of violence when it comes to serve the power of the state. The artist never directly refers to the 1965 killings when many Indonesian associated with the Indonesian Communist Party were assassinated by ordinary citizens and military people,[28] but hints at how violence tends to be justified by the state in the name of peace and harmony. Today, the army and militia-style organizations are still playing an important role in Indonesian society with violence returning to Indonesian politics.[29]

Theartist-researcher

History of Java (2018)

Courtesy Timoteus Anggawan Kusno, Centre for Tanah Runcuk Studies.

For Kusno, research and practice work simultaneously in a continuous back-and-forth movement, complementing his process of thinking and creating. He works with archives and literature but engages also in fieldwork in order to feel lived experiences, to share intensive discussions and grab reality as a counterpoint to his scholarly research. Participation and collaboration drive also his practice and methodology of work.

The artist as archivist

The CTRS is based on Kusno’s on-going collection of archive materials dealing with the Dutch colonial period in Indonesia, and in particular with the Javanese rituals, gathered during the artist’s various research trips and research on Internet. Although mixed with artistic artefacts, these archives constitute an important part of his exhibited work and a critical source for his inspiration.

In fact, at the beginning of the project, all of the archives from the CTRS were fictional, but as the Centre developed, Kusno introduced actual archives that he combined and transformed with fictional representations. In particular, he discovered the Rampog Macan rituals on an old colonial postcard found in an antique shop in2015. It featured a tiger in a pit during a ritual in the late 19th century.That image fascinated him and pushed him to engage into further research on the ritual and its context, leading ultimately to The Death of a Tiger. Atfirst, he accessed the online archives from the Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies,[30] but later delved into the archives from the Leiden University Library. At that time, he was searching all kinds of documents and representations, photographs, notes, maps and visual materials pertaining to tigers, related beliefs and rituals as well as records from the colonial period, but he confesses having been “distracted and fascinated” by the number of archives he found there.[31] During a residency at Rijksakademie in Amsterdam, he also accessed the archives and collection of theTropenuseum and Rijksmuseum.

The Rampok Party inKediri (Rampokpartij te Kediri), Blitar Palace Square, Approx. 1900.

Photographer: Herman Salzwedel, published by Masman & Stroink, Semarang.

These archives are either displayed by the artist in the framework of his exhibition, or transformed and combined with his artistic artefacts. The whole collection is available on the website of the CTRS, and each piece comes with a title, its source and a date. Archivist, Sue Breakell underlines the necessarily objective dimension of archives, arguing that the archivist should “describe material neutrally, document what they do to the archive, and intervene as little as possible if an original order is discernible in the papers.”[32] Curating the archives - let alone transforming them, is a way to intervene and to introduce discourse in what is supposed to remain neutral. As such, Kusno does not work as an archivist but rather borrows the tools and methods of the archivists in order to challenge their authority and their status as instruments of power. The juxtapositions of real and fake archives allow the artist to decontextualize his research material and to contextualize his fictional narratives simultaneously.

Fieldwork

Archive, Siloeman Matjan[1] 2018.

Courtesy Timoteus Anggawan Kusno, Centre for Tanah Runcuk Studies.

Academically, Kusnowas trained as an ethnographer, and he feels familiar with this approach, both epistemically and practically. Fieldwork, for him, is a way to expand, deepen and question the archives, which are thus confronted to the reality of memory and of people. How history is remembered, commemorated, performed or even how it has been forgotten… By meeting people, engaging discussions about history and about individual perceptions of the past and the present, the artist wishes to open the official narratives to periphery voices from the daily life.

In the field, Kusno has no specific methodology of work, but his approach is inevitably informed by his training as an ethnographer. He collects and exchanges stories with people by watching, talking, listening, and spending time with them, focusing in particular on stories about indigenous beliefs, shamanistic healing and rituals, such as the ones practiced by fishermen from the Northern Coast of Java (Pantura), before and after sailing. He also delved into the cosmological beliefs of different communities, like the people inhabiting the slopes of the Merapi Mountain, who have developed spiritual relations with the volcano, or the villagers living in the special province of Gunung Kidul. These research findings are not visible in his artwork, nor in the CTRS and, as such,the artist is not working as an ethnographer who would describe systematicallya specific community or a group of people. However, these findings constantly nourish the artist’s practice: they accumulate, transform, and inform his creative process in the long term.

Scholarly research and literature

Reading literature and scholarly texts have played a key role in the artist’s research process and practice, and discourses, under the form of notes, essays or various publications, are pervasive in the CTRS and accompany the visual artworks.

Javanese writer Pramoedya Ananta Toer’s Buru Quartet,[33] and Multatulis’s Max Havelaar classical anti-colonial 1860 novel have been very inspiring for the artist. They shed light on the complex layers of Indonesian past, and on how the marriage of colonialism and feudalism had deeply shaped Indonesian society. During his undergraduate years, in the framework of an informal reading club,[34] he discovered the Magic Realism movement, a literature style that mixes magic with reality in order to extend reality, and that is often associated with post-colonial literature.[35] For the artist, this style has the potentiality and power to “talk about something without talking about it,”[36] and played a key role in his artistic choices. In fact, the whole project of Tanah Runcunk, with its development of plural narratives, is imbued by Magic Realism and could be understood as a proposal to consider reality, including historical events, from an expanded perspective that would include imagination and wonders. In particular, the way he combines very realistic and scientific details, including Latin names, with imaginary figures resembles Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges’s scrupulous descriptions of absurd parts of reality.

Besides literature,the CTRS and Kusno keep referring to various scholarly works, both in Indonesian and English language, that the artist shares willingly. The scope of the bibliography is large, from post-colonial texts to more specific studies on Indonesia, literature references and anthropological books including for example Clifford Geertz, Benedict Anderson and James Siegel’s articles and reference books, Laure Donaldson’s post colonial and feminist critique, Peter Boomgaard and Robert Wessing’s essential studies on tigers. There are also essays by Professor of comparative literature Fairy Wendy and texts by Indonesian author Seno Gumira Ajidarma, known for his combination of reality and fiction used to address sensitive political issues.

The Unfinished Questof Tanah Runcuk,2018

Water color on aged paper, 750x690mm.

Courtesy Timoteus Anggawan Kusno, Centre for Tanah Runcuk Studies

A collaborative work

For the CTRS, Kusno collaborates with real scholars who contribute to the publications published online on the Centre’s website, under their real names or under pseudonyms. The artist invited them to respond freely to the fictional construction of Tanah Runcuk, using any form they would like. As such, Tanah Runcuk becomes an open platform working as an “empty signifier,” where these scholars can develop their thoughts, share their knowledge or questions. Kusno writes many essays as well, either under his name or under a pseudonym, but proposing a participatory space for dialogues and collaborations is an essential part of his methodology of work.[37]

An ethic of work

How should the viewer read and perceive the artist and his collaborators’ research findings? How to navigate between the real and the fiction? This confusion is at the core of the artist’s strategy. Nevertheless, Kusno does not aim at deceiving anyone and insists on a form of ethics when presenting his work. The origin or source of the ‘real’ collection is always written down and the artist puts a disclaimer in the epilogue of every publication as well as in the website of the CTRS. A contextual background appears, presenting Tanah Runcuk as a “in-between space; between presence and absence, between fiction and reality, between fantasy and history.”[38] Then, there is another“Disclaimer” where the real names of Kusno’s collaborators are noted, together with a renewed emphasis on the fictional dimension of the territory and of the Centre. The style and layouts suggest a kind of danger in misreading the textsor in misinterpreting the images, and one can read this satirical warning:“Again, please read, reread, and distrust the text carefully.”

Artistic transformations of the research findings

A fictional “lost”land

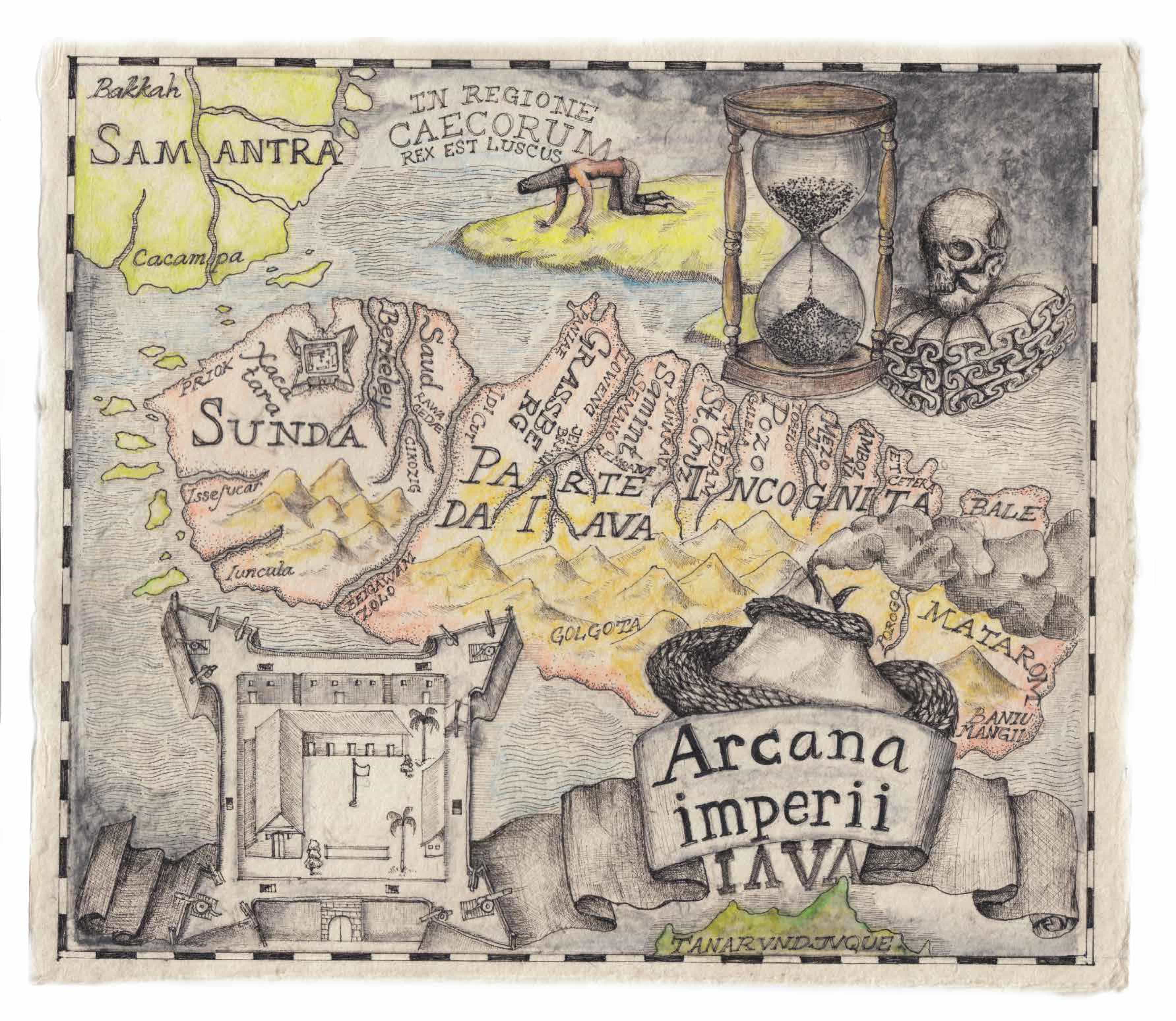

Map Arcana Imperii(2017)

Courtesy Timoteus Anggawan Kusno, Centre for Tanah Runcuk Studies.

Tanah Runcuk is a fictional lost territory that serves as an open and liminal space where Kusno’s artworks can develop. In order to move away from the centralization of power in Java, Kusno chose a name with a Melayu consonance, yet the exact location of this former colonized land remains a mystery. Within this framework, the artist invents a dense and complex network of narratives that connect, drive and generate multiple artworks responding to Indonesia’s colonial past and legacy.The Centre of Tanah Runcuk Studies collect and gather all this production, which ranges from photographs, drawings, paintings, essays, films and artefacts. The artist also produces antique-like furniture for the display of his artworks, usually made from old djati wood, which is the traditional material used for high quality furniture and houses in Java, including the palace during the colonial times. The hinges, locks, padlocks, handles are antiques from the northern coast of Java.

“Magic realismis informed by non-Western concepts of reality with a tolerance of magic much higher than Western understandings of reality.”[39] Imagining fictional realities allows the artist to embrace a larger perception of reality that includes the invisible, imagination and beliefs, usually disregarded when it comes to write history. This unseen part of reality can actually be empirically reached by certain communities or shamans, and appears to be visible in Tanah Runcuk. Weretigers, for example, are very common there, and can be seen either standing or crawling. The local people have often no head or a skeleton head. They are said to be intrepid and are represented taming or riding horses whose heads have the form of a megaphone. The style of the drawings and paintings is naïve,and often carries a certain amount of humor bore by the absurdity of the scenes.

Memento Mori paintedby unknown artist (portrait of JP Coen). Collection of Centre for Tanah Runcuk Studies.

Courtesy Timoteus Anggawan Kusno, Centre for Tanah Runcuk Studies

“My approach twists the fluidity of fantasy and history.”[40]The artist’s imagination is canalized, though, since the chosen styles and mediums need to match the style, color, and material from the archives and to follow the artist’s narratives so that the whole universe and identity of Tanah Runcuk remains consistent. However, once in the creative process, Kusno also improvises and let go his intuition. Some images are recurrent and become recognizable elements from Tanah Runcuk, such as the portrait of Jan Pieterszoon Coen, represented half-alive, half-dead, who appears in many drawings but also under the form ofa sculptural bust. Weretigers are also pervasive, in photographs, artefacts ordrawings.

Constructing archival material

The Terror of Coconut Island

Unknown artist (Collection of the Centre for Tanah Runcuk Studies)

Courtesy Timoteus Anggawan Kusno, Centre for Tanah Runcuk Studies

The Terror of Coconut Island, a painting dated 1602 and originating in the SocietasTanaruncia, is for instance an archival production of the artist. It was inspired by the tragic story of the Banda Islands whose inhabitants were massacred by the Dutch East India Company under the command of Jan Pieterszoon Coen, who established there the trade monopoly of nutmegs. In this image, Kusno diverts the colonial aesthetic of mooi Indie usually representing atropical paradise: beyond the blue sky and behind the coconut trees, the islandis in fact burning and the volcano is erupting. The artist invites the viewer to contemplate from afar this tragic spectacle, as if nothing could be done or as if no one felt the need to intervene. Put back in today’s context, one could wonder to which passivity the artist is referring to: the colonial absence of responsibility and/or the inability of the Indonesian state to reform its institutional models? In the exhibition The Untold Story of Archipelago(2017), the painting was displayed in a wooden spices box which contains of thousands of nutmegs from the Banda Islands, together with flintlock colonial pistols. For Kusno, the spices had “the strong smell of gold and blood.”[41]

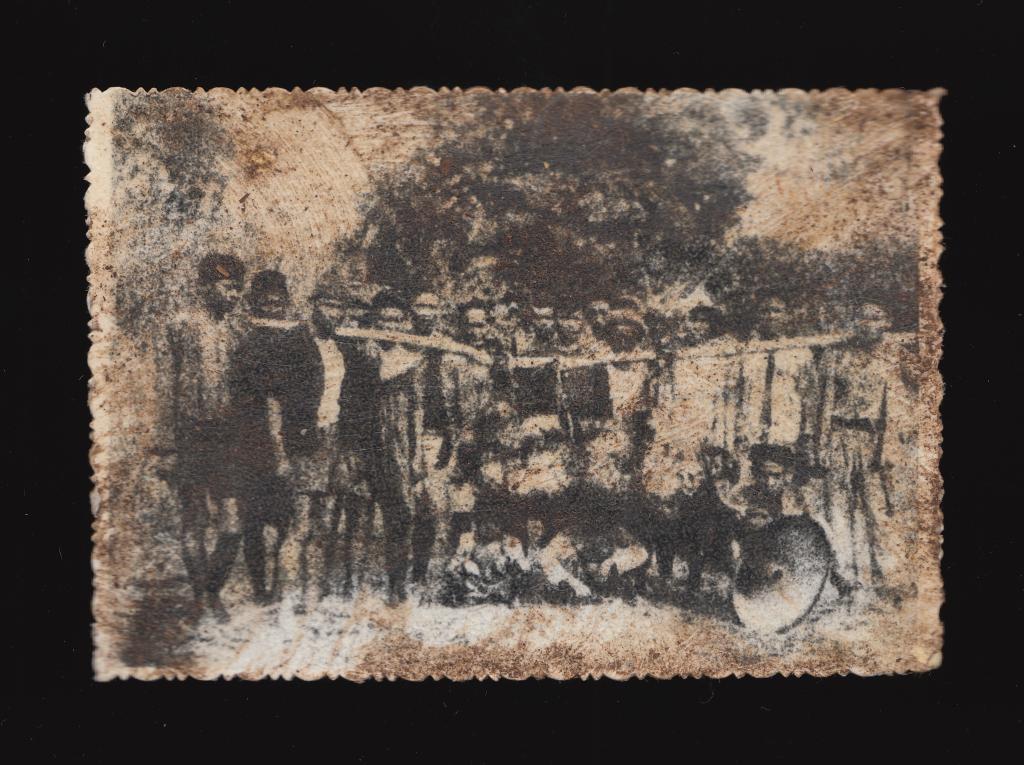

Villagers posing in the front of a dead tiger. May 1941 at Malingping, Banten (H.Bartels/Tropenmuseum).

unknown artist. Centre for Tanah Runcuk Studies, Societas Tanaruncia.

Courtesy Timoteus Anggawan Kusno, Centre for Tanah Runcuk Studies

Many photographs pertaining to the ritual and to the Javanese tigers have been modified by the artist so that they look more ancient. The 1941 archival photograph Villagers posing in the front of a dead tiger from Tropenmuseum collection was for instance printed on archival paper, scanned and modified by the artist using Photoshop, pulling up the grain so that it turns more visible. He also added some typical elements from Tanah Runcuk, such as the megaphone on the bottomright. It stands as a symbol of modernity, in contrast with Javanese traditional way of life. After reprinting the photograph, Kusno dipped it in the rust for some time, and after obtaining the relevant tone, soaked it again in coffee in order to get sandy little grains on the surface. Finally, he coated it with glue by using brush and cut its edges.

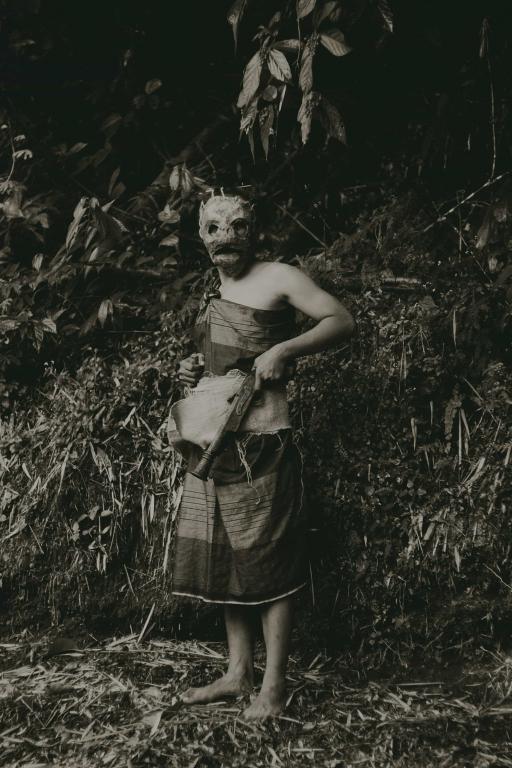

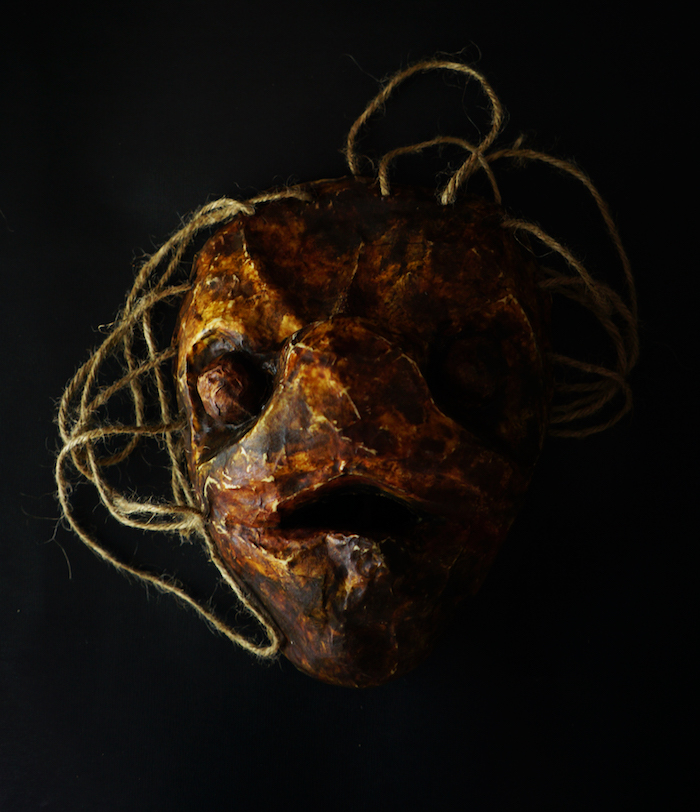

Artefacts (Mask) of Rampokan Siluman Macan (collection of Centre for Tanah Runcuk Studies)

Courtesy Timoteus Anggawan Kusno, Centre for Tanah Runcuk Studies.

The embodiment and evidence for the existence of were tigers had also to be produced by the artist.[42] Kusno invented a weretiger mask,artefacts, and produced archival photographs that feature them, as if taken by surprise in the wild at night. The outlines of the images are often blurry, the quality very poor and their origins absolutely mysterious.

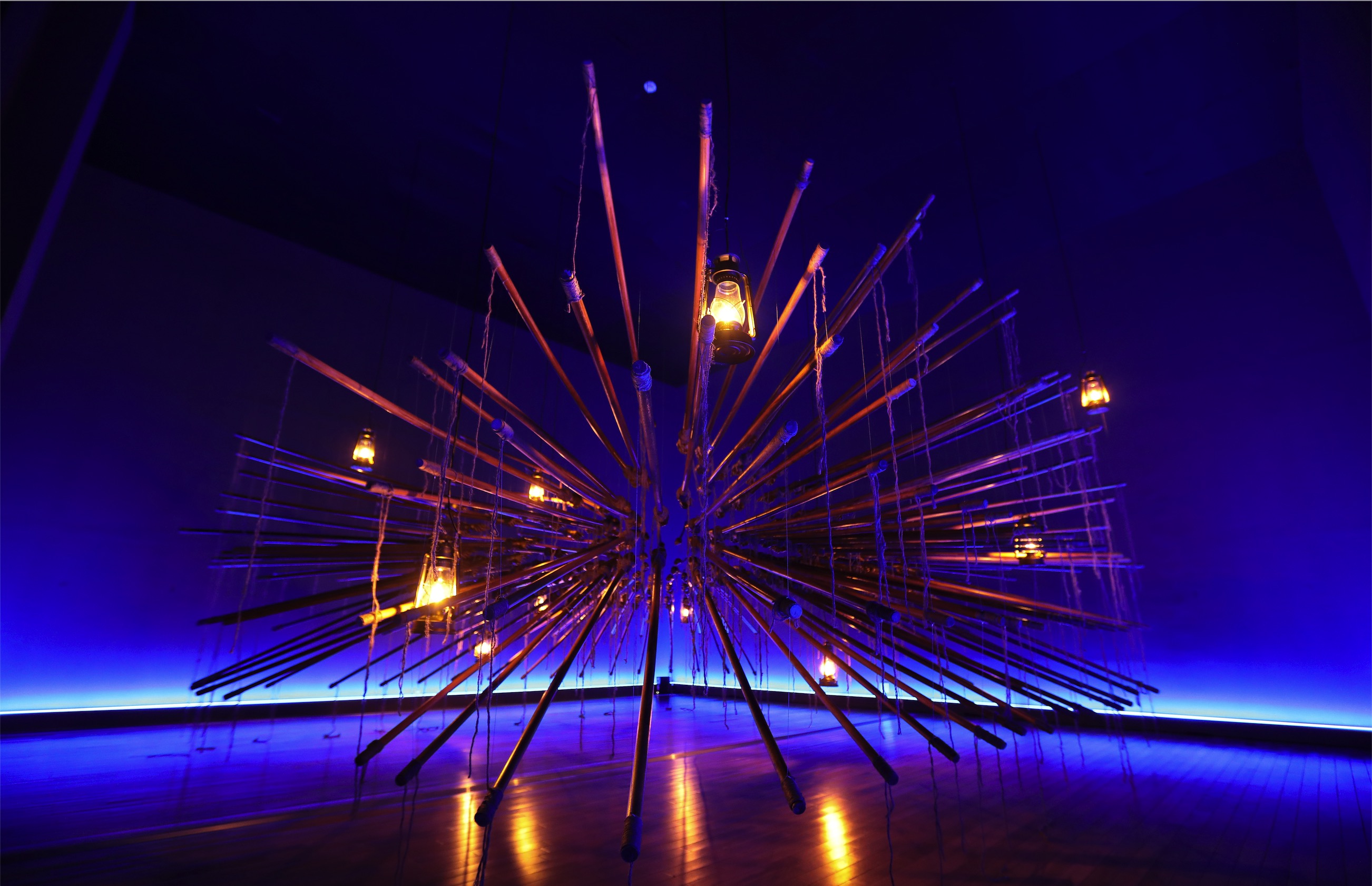

The Death of a Tiger and Other Empty Seats in How Little You Know About Me exhibition, curated by Joowon Park,2018.

National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA), Korea.

Courtesy of MMCA,Korea and the artist. Photo by Moon June Hee.

There is a strong contrast between the museum-like exhibition The Untold Stories of Archipelago (2017) and The Death of a Tiger (2017) or its more recent version The Death of a Tiger and Other Empty Seats (2018): on the one hand the display of documents and archives, which could be seen as a bitdry, and on the other hand a warm and dynamic performance staging ametaphorical interpretation of a Rampog Macan ritual. From the same research findings, Kusno is actually exploring different artistic languages to produce and transmit knowledge.

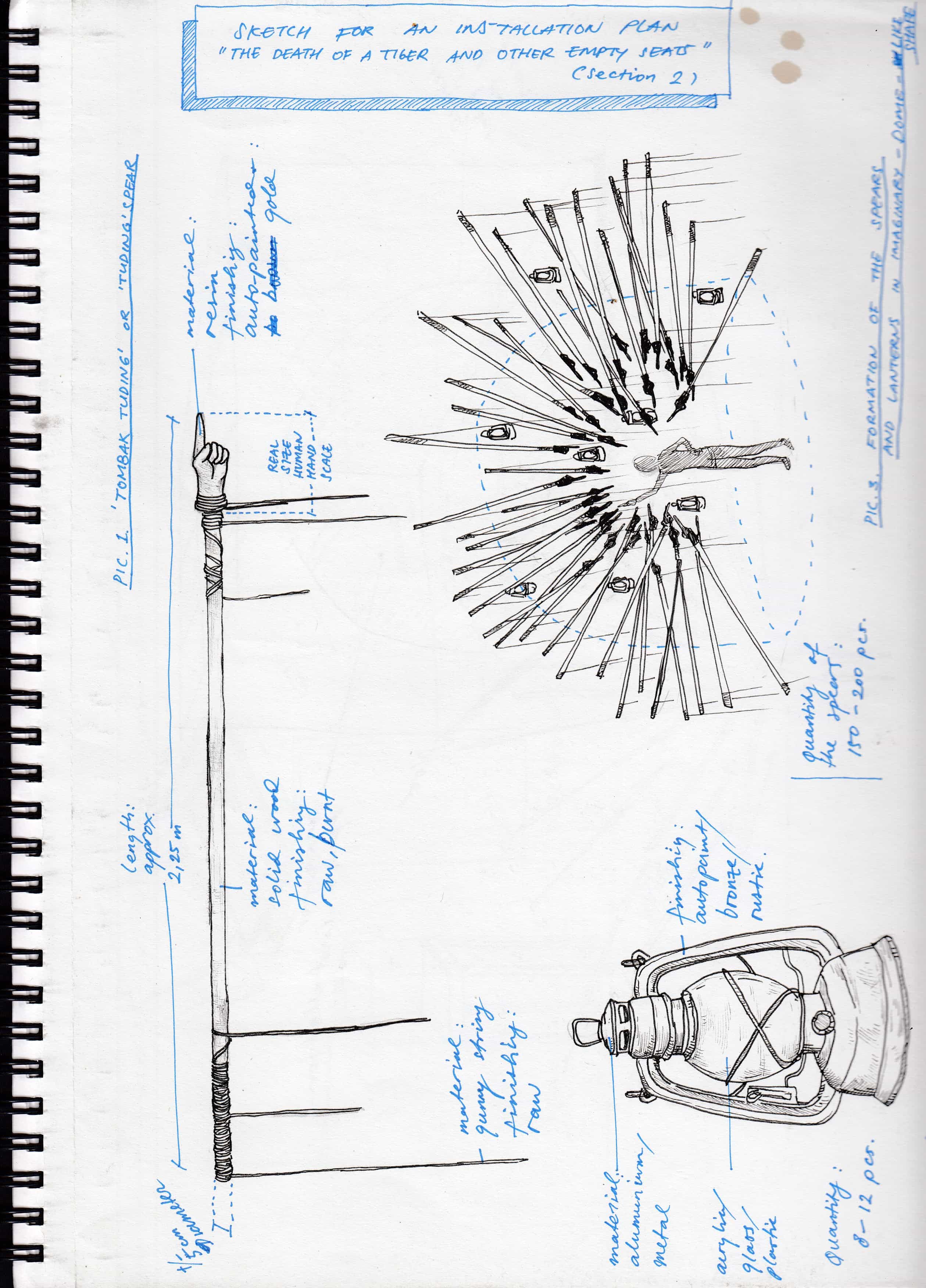

In a dark room, only lightened by storm lanterns, a group of singers face the wall, each one separated from the others in a circle. In the middle, a bunch of spears hung from the ceiling seems to point to and accuse one of them: instead of a head, they finish by a hand with a raised finger. The choir sings an original composition inspired by Mozart’s Requiem Lacrimosa movement, transformed as a tiger requiem: the artist chose to focus on this very moment of tension when the tiger dies, killed by the crowd. The juxtaposition of a classical European music with a Javanese ritual collides almost ironically as the lyrics say “Full of tears will be that day When from the ashes shall arise The guilty man to be judged.” Again, we wonder how to interpret this contemporary version of the colonial and feudal ritual: a collective, religious, juridical judgement? The staging brings back the ambiguous role of the people when it comes to justice and informal laws. This time, it seems that the artist invites the public to be part of the crowd and to feel the possible effects of such a gathering, intuiting what it must have been to belong to the crowd that condemned and killed the tiger. Obviously, and beyond the Indonesian context, these kinds of massive gathering have often a dangerous impact on the mind.[43]

Drawing sketch of the installation.

Courtesy Timoteus Anggawan Kusno, Centre for Tanah Runcuk Studies

Demonising others and the legitimation of violence

Kusno constantly revives the archival material to question the legacy and imprint of the past. In particular, he investigates how the colonial heritage merged with local traditions in a way that might inform specific contemporary patterns or beliefs. The documentary film entitled Others or‘Rust en orde’ (2017) produced by the CTRS, is presented as a remake from a former film narrating the tradition of Rampog Siluman Macan that was supposedly censored and lost for its most part.[44] The team is said to have reinterpreted what was left, using tape-recorded interviews. From the start, there is thus a large part of mystery about this documentary and no detail is given about the authorities that censored the original nor about the identity of the interviewees, whose names are said to be confidential. This introduction immediately contextualizes the film in the present times, with the censorship implicitly referring to the New Order regime. At that time, artistic production used to be strictly controlled by the state and most of the documentaries were funded by the government and created in order to satisfy state ideologies.[45] For Kusno, this is a way to anchor the film in the collective memory and in the post-dictatorial regime,when the euphoria was pervading the country, with the hope for deep reforms.

Others or 'Rust en Orde,' 2017. Still image. Four channels video installation.

Courtesy of the artist and CTRS.

Others or ‘Rust enorde’is organized in three parts that follows three distinct interviews and narratives. We do not see the interviewees who are embodied by a recording machine, staged in various landscapes as if it was the last remnant of a lost past, delivering a last message. Contemporary images of the countryside and of daily life in villages alternate with the archival images – old black and white postcards and documents from the colonial times or the artist’s drawings, animation and photographs. The atmosphere of mystery is strengthened by a stressful music that rhythms the interviewees’ voices which are also hesitant, reflecting a fear from the witnesses. The three stories, although very different, emphasize the positive role of the Rampog Siluman Macan ritual, and the killing of specific persons, as an efficient way to bring back order and harmony in the society. These victims, represented as weretigers, shamans or marginal individuals, are said to be the ones who are breaking the rules of the society, and who need to be sacrificed. However, the first interviewee seems to doubt about what really occurred when his grandfather’s uncle disappeared and was put in a cage as he suddenly happened to be a “tiger stealth” who had to be killed.

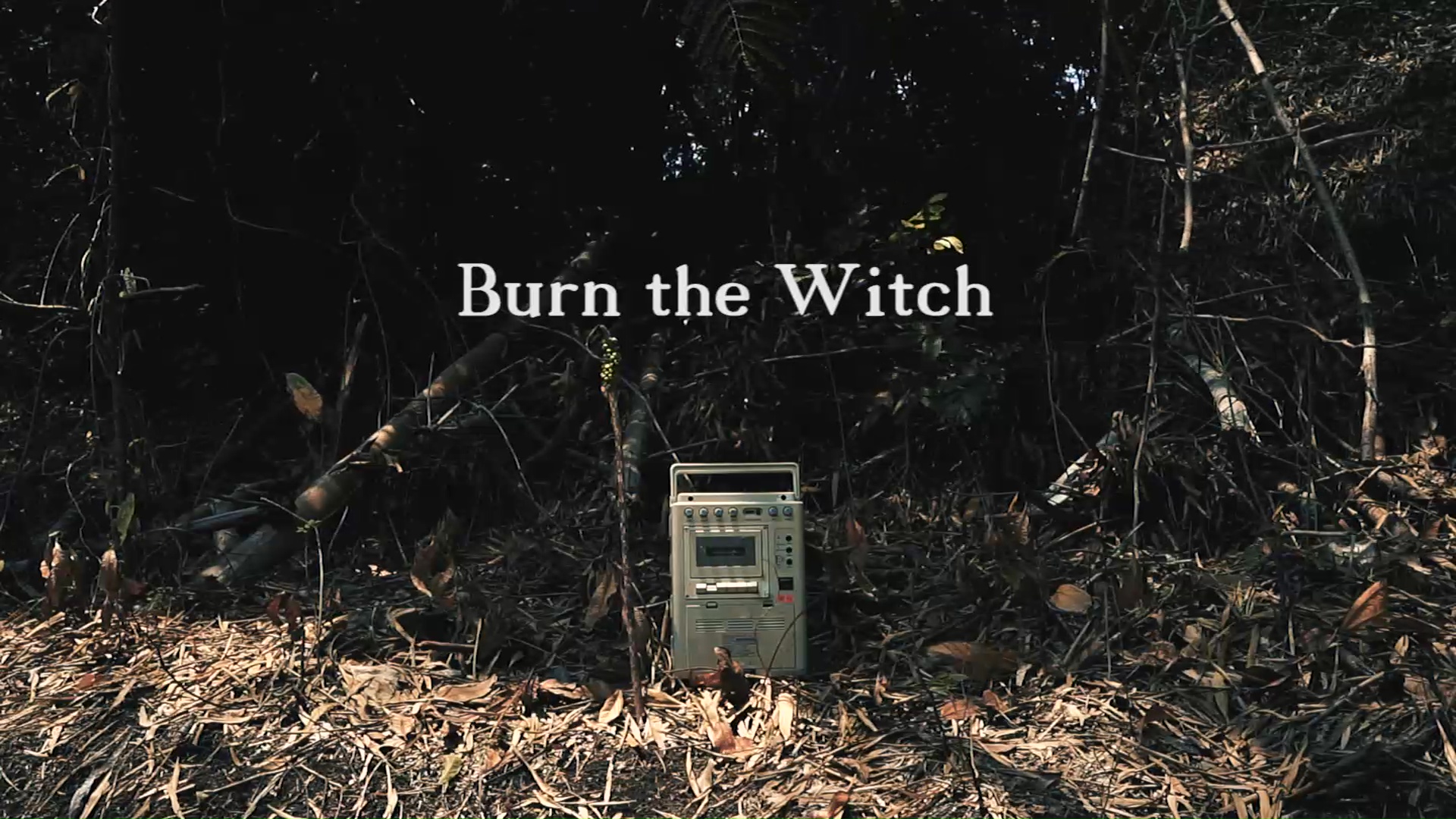

Literary, ‘rust enorde’ means tranquility and order. The Dutch colonizers were using this idea to discipline and repress any threat that would weaken the legitimation of their authority. In the name of harmony, they had the ability to exile and kill anyone considered as “enemy” or “rebel” without any trial. According to Peter Boomgaard, the rituals originated in two non-exclusive factors: the need to kill more tigers, who represented an increased threat at that time, and the desire to demonstrate state power.[46] Implicitly, we are tempted to link the cruel ritual of Rampok Macan with more recent events, and in particular with the 1965 massacres and their legacy: the threat, at that time,was embodied by the Indonesian Communist Party. Historian Robert Cribb notes in particular that the Suharto regime used the memory of the killing “to reinforce its power, as an example of both what it would do to its enemies and what Indonesians would do to each other if they were not restrained by firm government.”[47] For the artist, this form of repressive power, its ideology and the state legitimization of violence persist today, despite the end of the authoritarian regime of Suharto. In the film, the second interviewee in a part entitled Burn the Witch praises the organization of raids that allow the collectivity to get rid of anyone who could be perceived as a threat, reflecting how such ideologies might have been collectively appropriated by the people. The work could be perceived as a catharsis: in the narratives, the fear of others and the search for scapegoats are so clearly articulated that they become frightening. In the end, one cannot help but wonder who are the contemporary weretigers and how one face, deny oraccept their difference. However, the film is never moralizing and the testimonies, like the witnesses’ voices, are wrapped with magic and doubt: after all, this is a fictional documentary, featuring imaginary interviews.

Burn the Witch, still image from the4-channel video Others or 'Rust en Orde,' 2017.

Courtesy of the artist and CTRS.

A constructive confusion

Archive Tombak Toeding 2018.

Courtesy of the artist and CTRS.

Kusno’s work is always ambiguous and none of the symbols he uses are straightforward. Tigers, for instance, represent evil and chaos, but also holy men, and there are many stories of shamans transforming into tigers after their death. In the Indonesian culture, their symbolic meaning is complex: the animal could be inhabited by ancestors and could even represent the king himself: Boomgaard mentions trials by tigers,and in that case the tiger was praised for its moral judgment.[48] During the fights, the buffalos represented the Javanese people while the tigers represented the Europeans and local people were disappointed if a tiger would win. From this perspective, it seems ironical that the Dutch used it to legitimize their authority since their effigy was systematically killed at the end of the fight. Similarly, the spears are not necessarily the weapons used to kill the victims of such rituals without any trial and, above all, in a very unfair manner (the whole crowd against an exhausted tiger that already fought against another animal). In the past, spears were the symbol of resistance and during the Java War (1825-1830), Dipanagara and his men used bamboo spears with sharpened tip as weapons, which are said to have “scared the Dutch away.”[49]

These ambiguities, together with the constant uncertainties created by the entanglement of real and fake archival material might lead to a certain confusion, strengthened by the dense contextual background of the work. From the start, the location and name of Tanah Runcuk are presented as being problematic, and the tone is set:“up to now Tanah Runcuk itself is in grey area in the context of scientific debate.”[50] The artist keeps introducing doubts in the mind of the reader, creating a feeling of discomfort. Although the writing style is very scientific, the artist’s collaborators share also constantly their own doubts about the identification of their sources: “CTRS suspects that,” “from all the archives we tend to assume that,” “sources are difficult to interpret” etc. to the point that the whole process becomes comical. In addition to fictional elements, the artist creates narrative gaps and only proposes a fragmented and non-linear approach of history, breaking the given chain of causality, temporally, and spatially. His vision of history is thus left purposely open for the audience to create his or her own narrative. Besides, for him, confusion is an inevitable consequence of dealing with institutions and complex issues. “I have to admit that’s the part of the holistic experience.”[51]

L'Histoire de Rundjuque 2018.

Courtesy of the artist and CTRS.

Working in-between fiction and reality stimulates critical thinking and, as told by the disclaimer, invites viewers to remain active when facing any piece of work and archives. As such, this confusion engages positively the viewer, constantly confronted with a dilemma, which could be similar to the reading of a fantastic novel from the Magic Realism movement: shall we read the work from a realist perspective, and reduce its artistic and magic dimension to a rational interpretation, or shall we approach it from a purely artistic point of view, with the risk to miss its relevance in its ability to question our contemporary societies?[52] In fact, there is no solution to this dilemma for the artist purposely avoids any form of dualism. Similarly, while most of the artists engaged today with archive invent “counter-archives and thus counter-narratives,”[53] Kusno does not contest any specific narrative nor oppose one mode of narrative to another, because fiction brings forth a third element that breaks this duality and brings back complexity against any form of binary simplification: the colonial legacy does not oppose a traditional heritage, for instance, since it was built upon it. This complexity, inevitably, conveys its part of confusion that reflects nothing but the complexity of reality.

Conclusion

Kusno’s engagement in research derives from his desire to re-activate, question and deconstruct the existing archival material in order to shed light on neglected or hidden historical facts from the past and on their legacy in today’s Indonesian society. His artistic and sometimes satirical interpretation of history and of the language of social sciences reflects his aspirations to explore new and independent modes of knowledge production that would acknowledge ideas and concepts hitherto alien to the West. His fieldwork and collaborative works nurture his investigations and connect his research findings from the past to the present, creating links between the colonial system, traditional Indonesian rituals and beliefs, the power structure of the local elite and today’s specific patterns of the Indonesian society.

The artist’s research findings are entangled with his own creation and, in the end, true and fake archives make one to constitute his artistic production. Among the diverse narratives, the viewers can nevertheless navigate and grab some historical facts, provided that they read carefully and critically all the available sources. Above all, his constellation of artworks triggers a desire to delve into Indonesian past and to question the construction of history and of the ideologies that shape acountry’s identity and society. Through the artist’s various artistic languages and experimentations, one can physically lose one’s benchmark and reference points, and feel the necessity to enlarge one’s vision of reality. The merging of realism with fantasy, rationality with beliefs, and science with magic is an invitation to go beyond any form of dualism and a call to embrace a plurality of voices and perspectives.

Kusno’s research-based practice reflects a wider trend in Southeast Asia, with artists increasingly working in the fields of ethnography and history, notably in order to better grasp today’s complex reality and to question the construction of national historical narratives.

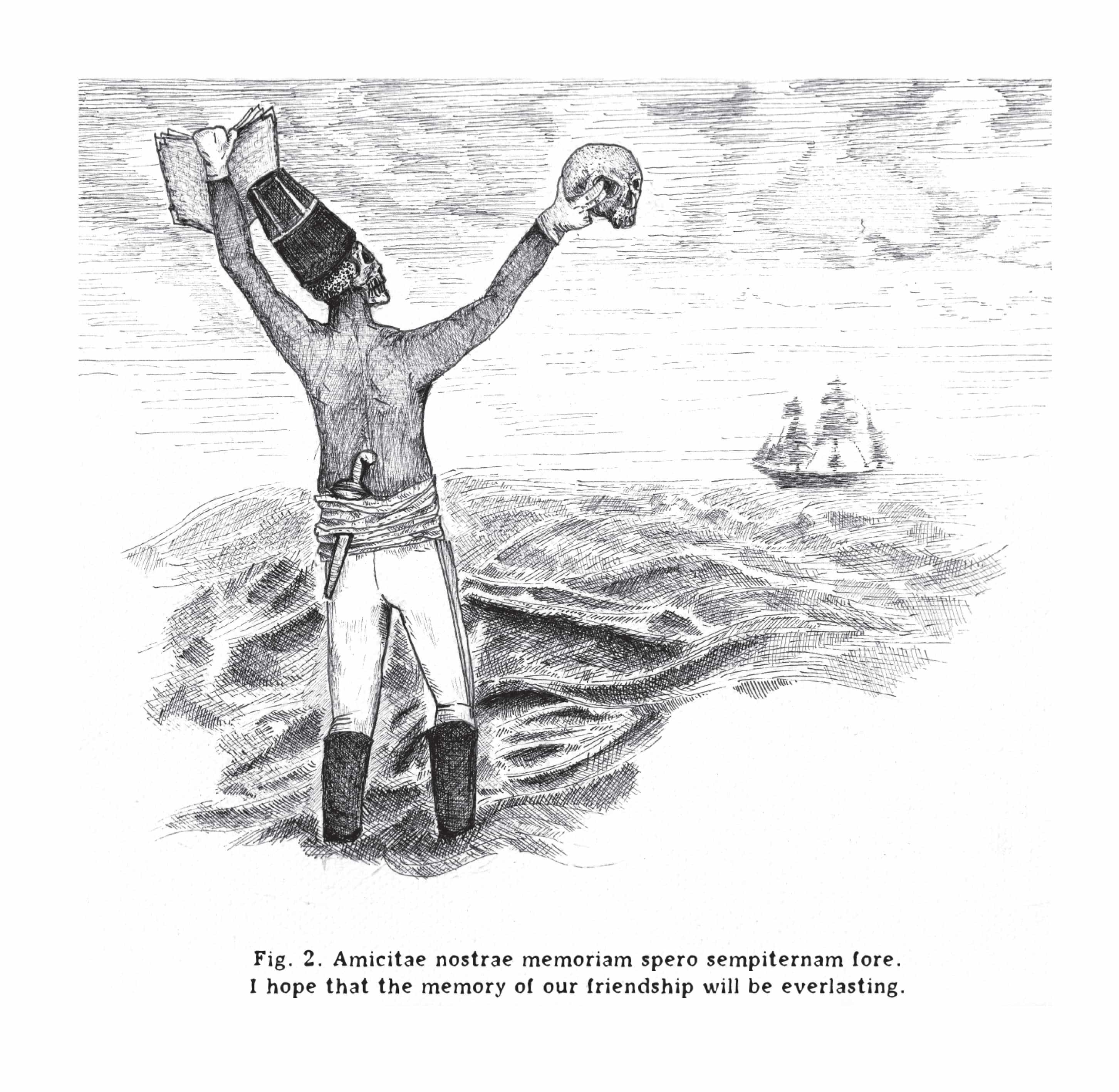

I Hope that The Memory of Our Friendship Will be Everlasting

Drawing, 2017

Courtesy Timoteus Anggawan Kusno

[1] A large part of thecollection and publications, fictional and real, are available on the CTRS websitecreated by the artist: https://www.tanahruncuk.org

[2] The exhibition tookplace in Nov. 2014 at Kedai Kebun Forum in Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

[3] The exhibition,entitled Power and Other Things: Indonesia & Art (1835-now) wascurated by Charles Esche and Riksa Afiaty. It took place at the Centre for FineArts Brussels (Bozar), Belgium in 2017.

[4] This article is basedon the author’s conversations with the artists taking place between Sept. 2019and July 2020.

[5] More on the colonialtimes, see for instance the reference book Ricklefs, Merle Calvin. A historyof modern Indonesia since c. 1300 (2 ed.). Basingstoke; Stanford, CA:Palgrave; Stanford University Press, 1991.

[6] Oostindie Gert,“Dutch Attitudes towards Colonial Empires, Indigenous Cultures and Slaves,” Forum:Urban Culture in the Eighteen Century Dutch Republic, 1998: 351

[7] Wood, Michael.Official History in Modern Indonesia: New Order Perceptions and Counterviews,BRILL, 2005:69.

[8] See in particular thelife and struggle of Prince Dipanagara in Carey Peter. The Power of Prophecy.Brill, 2008.

[9] See the case studyWah Nu & Aung The Name. 请参考案例研究——瓦努和敦运昂“名字”系列作品.

[10] Wood, Michael. Official Historyin Modern Indonesia: New Order Perceptions and Counterviews, BRILL, 2005:41.

[11] Suwignyo Agus, “IndonesianNational History Textbooks after the New Order: What's New under the Sun?”Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, Vol. 170, No. 1 (2014):114.

[12] The Indonesian Visual ArtArchive (IVAA) was formerly the Cemeti Art Foundation founded in 2006 inYogyakarta.

[13] Wardani Farah, “Finding a placefor art archives” Wacana Vol.20 No2(2019): 209-232.

[14] E-mail conversation with theartist, June 2020. All quotes from the artist come from a series of e-mailconversations with the author that took place between Sept. 2019 and July 2020.

[15] Antariksa, for instance, hasbeen doing research on the Japanese occupation of Indonesia for years;Lifepatch, a collective of artists founded in 2012, have also conductedresearch in historical museums in the Netherlands, looking for colonialarchives, in particular for their project The Tale of Tiger and Lion.

[16] Gerke Solvay and EversHans-Dieter, “Globalizing Local Knowledge: Social Science Research on Southeast-Asia,1970-2000,” SOJOURN: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia Vol.21,No1 (2006): 2.

[17] On the New Order and the past,see in particular Wood Michael. Official History in Modern Indonesia: New OrderPerceptions and Counterviews, BRILL, 2005.

[18] Suwignyo Agus, “IndonesianNational History Textbooks after the New Order: What's New under the Sun?”Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, Vol. 170, No. 1 (2014):114-115.

[19] E-mail conversation with theartist, June 2020.

[20] Dragojlovic Ana, BloembergenMarieke and Schulte Nordholt Henk, “Colonial Re-Collections: Memories, Objects,and Performances”, Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, Vol.170, No. 4 (2014): 438-39.

[21] E-mail conversation with theartist, June 2020.

[22] See in particular AndersonBenedict, “Old State, New Society: Indonesia’s New Order in ComparativeHistorical Perspective,” The Journal of Asian Studies Vol. 42, No. 3(May, 1983):477-496.

[23] See for example Meuleman Johan,“Between Unity and Diversity: the construction of the Indonesian nation,”European Journal of East Asian Studies, 2006, Vol. 5, No. 1, 2006: 45-69.

[24] Artist’s statement “The Death ofa Tiger and Other Empty Seats,” courtesy of the artist.

[25] More on the ritual, see inparticular “Tiger and Leopard Rituals at the Javanese Courts 1605-1906,” inBoomgaard Peter. Frontiersof Fear: Tigers and People in the Malay World, 1600-1950. Yale UniversityPress, 2001, 145-166.

[26] Kusno, “Out of Darkness ComesLight,” online essay from the CTRS website.

[27] Boomgaard Peter, 2001. Ibid.157.

[28] According to the differentsources, between 100,000 to two million people were killed but that numberremains opaque. James T. Siegel emphasized the “normalization of the massacre”which suggests a form oflegitimation of the violence.Siegel T. James. “Indonesia: A Partial Appraisal” Ithaca 100 (Oct 2015):31.

[29] Cribb Robert, “UnresolvedProblems in the Indonesian Killings of 1965–1966,” Asian Survey, Vol.42, No. 4 (July/August 2002): 551. See also Siegel about the 1983-1984 massacrein Siegel T. James. A New Criminal Type in Jakarta. Durham &London: Duke University Press 1998.

[30] This is probably the largestexisting collection of documentation from the Dutch East Indies. Most of thearchives are photographs that the Royal Netherlands Institute of SoutheastAsian and Caribbean Studies began to collect from 1890 for documenting the lifeof the Dutch East and West Indies. They are now accessible online at https://digitalcollections.universiteitleiden.nl/imagecollection-kitlv.

[31] E-mail conversation with theartist, June 2020.

[32] BREAKELL Sue Perspectives:Negotiating the Archive, Tate Papers 9, 2008. Available at:www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tatepapers/09/perspectives-negotiating-the-archive(accessed 3 May 2018)

[33] Pramoedya Ananta Toer(1925-2006) is a famous post-independence Indonesian author, known for hispolitical engagement. The Buru Quartet, written in jail and censored for manyyears, comprises The Earth of Mankind, Child of All Nations, Footsteps, andHouse of Glass.

[34] The club was called LingkarBatu (The Circle of Stone) and was composed of artists, musicians oractivists. They collectively published a monthly photocopied zine called Repertoar.

[35] More on the movement, see forexample Kluwick, Ursula. Exploring Magic Realism in Salman Rushdie's Fiction.Taylor & Francis Group, 2011.

[36] E-mail conversation with theartist, June 2020.

[37] The Malalongke Journal, aseries of essays published in 2017 was the first results of the artist’scollaboration with ethnographers and historians. In particular, Kusno workedwith Pandu Yushina Adaba (researcher, Indonesian Institute of Science),Franciscus Apriwan (anthropologist, Brawijaya University), Heri Kusuma(historian, Realino Institute of Studies), Albertus Harimurti (researcher,Realino Institute of Studies), Irham N. Anshari (lecturer, Gadjah MadaUniversity), Windu W. Jusuf (writer, journalist) and was inspired by hisdiscussions with Dr. G. Budi Subanar (historian), Dr. Baskara TH. Wardaya(historian), Dr. ST. Sunardi (philosopher), Dr. Tri Subagya (ethnographer).

[38] Centre of Tanah Runcuk Studieswebsite. Available on: https://www.tanahruncuk.org/about/#disclaimer

[39] Kluwick, Ursula. ExploringMagic Realism in Salman Rushdie's Fiction. Taylor & Francis Group,2011, 10.

[40] Artist’s statement “The Death ofa Tiger and Other Empty Seats,” courtesy of the artist.

[41] E-mail conversation with theartist, June 2020.

[42] Boomgaard notes that a Chinesesource mentions a weretiger in Malacca in the early 15th century andthat the belief was documented from the early nineteenth century onward, butthere are – obviously? - no photographs representing these creatures. See Boomgaard Peter. Frontiersof Fear: Tigers and People in the Malay World, 1600-1950. Yale UniversityPress, 2001, 163.

[43] French Gustave Le Bon famouslystudied the behavior of individuals immersed in crowd and notes the possiblehypnotic state that it might triggers, and the absence of judgment. See Le BonGustave, The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind. New York: DoverPublications 2002.

[44]Siluman Macan refers toweretigers or man-tigers, tiger stealth.

[45] Hanan David, “ObservationalDocumentary Comes to Indonesia: Aryo Danusiri’s Lukass’ Moment, in SoutheastAsian Independent Cinema, ed. Tilman Baumgärtel (Hong Kong: Hong KongUniversity Press, 2012), 107.

[46] Boomgaard Peter. Frontiers ofFear: Tigers and People in the Malay World, 1600-1950. Yale UniversityPress, 2001, 154.

[47] Cribb Robert, “UnresolvedProblems in the Indonesian Killings of 1965–1966,” Asian Survey, Vol.42, No. 4 (July/August 2002): 559.

[48] Boomgaard Peter. Frontiers ofFear: Tigers and People in the Malay World, 1600-1950. Yale UniversityPress, 2001, 163.

[49] Kusno, “Out of Darkness ComesLight,” online essay from the CTRS website.

[50] From the CTRS website.

[51] E-mail conversation with theartist, Sept. 2019.

[52] I borrow here Tzvetan Todorov’sinterpretation of the fantastic in Magic Realist novel. See Kluwick, Ursula. ExploringMagic Realism in Salman Rushdie's Fiction. Taylor & Francis Group,2011, 14.

[53] Enwezor Okwui ArchiveFever: Uses of the Document in Contemporary Art Gottingen, Germany Steidle2008, 22.