Su Wei: Hi Biljana, I haven't seen your curatorial projects in China for a while. Recently, you have been working on the project “As you go ... roads under your feet, towards the new future”, which focuses on the ecology of art in the so-called One Belt and One Road region. In the unfolding of this project, we see that the rhythm and the way you have worked in the past seems to be different. Does this change of working method influence the exhibition “Repetition as a Gesture Towards Deep Listening” you curated at the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts Museum?

Biljana Ciric: Hello Su Wei. Thank you for reaching out and paying close attention to the changes in my work and thinking. I think it is very important for the curator to commit to opacity rather than visibility. That right for opacity is needed now more than ever before.

The pressure of constant visibility within the field of art follows the very logic of consumerism that I have been trying to distance myself from, using various methods. I perceive moments of visibility as fragile in the new world unfolding in front of us caused by the pandemic.

I believe the pandemic has influenced me deeply, and I have developed a true understanding of our interdependence as well as the urgency to start to learn to be a different kind of human in he world. My thinking and doing within both of these projects has been influenced by the above-mentioned, as well as thinking whether there is space for art as an essential service and how we reach for that. How we practice interdependence, how to respect knowledge structure that is not part of mine and create a space for that knowledge to exist in the world with dignity. How to care with, rather than care for, within curations is the main trajectory of both of these projects. And that ‘care with’ encompasses thinking with, walking with and spending time with art.

"Womanifesto"group gathering in Thailand

Su: As the first project of the first Trans-Southeast Asia Triennial, two projects were brought together, namely "Womanifesto" and "Spirit of Friendship". I can tell that you want to discuss the multiple and intricate connections within and between different local environments in Southeast Asia. You have been investigating and researching contemporary art in Southeast Asia since around 2007, and I get the impression that Southeast Asia is not simply an exotic region for you, nor a representative of the so-called Global South, but a place where organic practices take place, offering a diversity of sensibility and an intensity that is constantly overlooked. In this exhibition, I am particularly interested in the way you develop your research through "friendship" and "listening", thus avoiding the repetition of jargon that is often used to describe artistic practices in this region in a holistic way. Can you share with us some of the encounters that have impressed you in your research?

The chronology of Vietnamese contemporary art in "SOF"

Ciric: This was a cumulative process for me, as it took many years to understand how to position myself and my work within a region that I don’t belong to but feel deeply connected to. Through many of my projects reaching out for that very space that we frame as Southeast Asia, my curatorial gesture has always been creating space for encounters to happen, research to emerge as a start

of a possible relationship that is deeper and more engaging. Epeli Hau’ofa, in his seminal textOur Sea of Islands, proposes that we think about oceans between oceanic islands as connection points rather than spaces of separation.

The curator, for me, is that point of connection that the oceans in Hau’ofa’s text perform and enable. I think this stands not only for this specific public moment of the triennial event, but also for the book that was published in relation to exhibition histories in the region (From Exhibition Histories: towards the future of exhibition making China and Southeast Asia, published by Sternberg Press). All these have been intensified by the pandemic, along with the physical and ideological separations that we are all experiencing. No matter whether we are discussing it or ignoring it, it is there and it will last. Both of these projects provided modest gestures to reach out to the community that they are close to, and find ways of working together that are based not on the online world, but on physicality, intimacy and encounters that are taken from us. And this is something that I find important and precious in our future to come: how we can listen deeply to these practices and learn from them. Deep listening.

Artist Virginia Hilyard and her mother Shirley Hilyard created the work together Remember Yellow,plastic cement,model clay,pillow,2021

Su: The Womanifesto exhibition presents the reunion of the eponymous group of artists during the epidemic, a group formed in Thailand in 1997 by six Thai artists, writers and activists, who were loosely organized, but actively and widely united with artists from different parts of the globe. The group is a unique phenomenon in the discourse and reality of globalization, and they

are both collaborators and provocateurs of globalization with a cross-regional association and a practice that reaches out to local communities. The group's activities came to an end in 2008. When did you first become associated with this group? What kind of dialogue occurred between the reunion of the group and your curatorial concept?

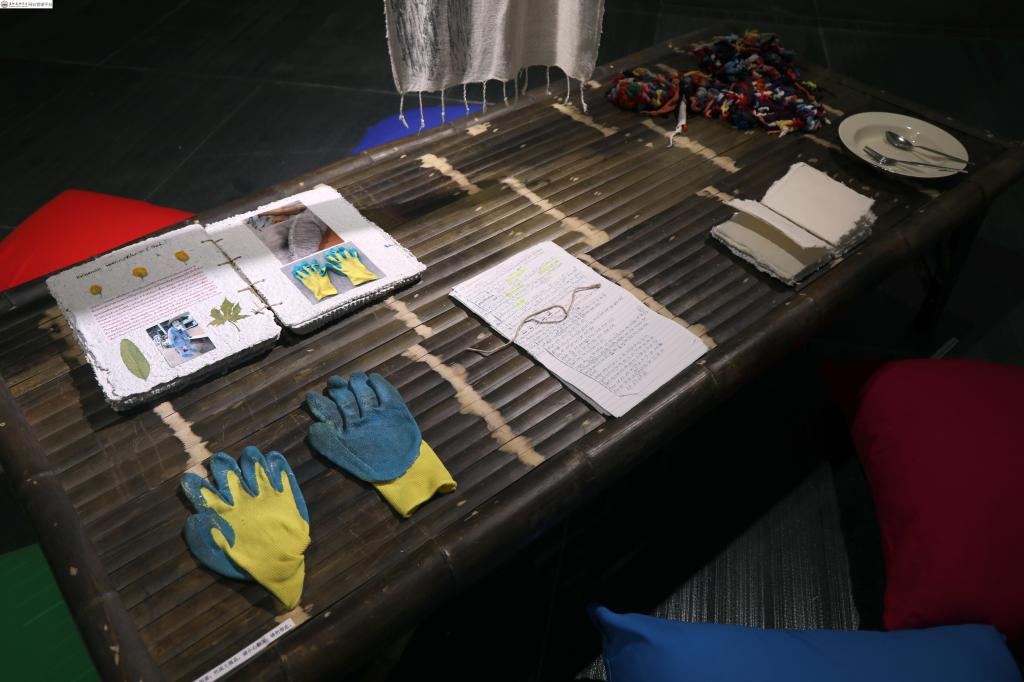

Ciric: My conversations with the group started with discussions with Varsha Nair, the founding member of Womanifesto, who is based at the moment in Baroda. As you might know, India is experiencing at the moment a tragic wave of COVID-19, with thousands of deaths per day. I checked on her, and she didn’t leave her house for three weeks. I was interested in Womanifesto and their closeness to life, their proximity to everyday moments in their work, as well as the importance of community and nature. On the other hand, I was always sad seeing their museological displays which take life out of it, thus creating a distance to objecthood that is there the moment you enter the museum. Archival material is safely stored in glass cases, and the works are on the walls. I was interested in trying to find a different way of working with Womanifesto, in order to pertain to that proximity to life. Their existence and mode of working has much more than just objecthood, so we have tried to find ways to work around these issues. During the conversation, she told me that they actually came together as Womanifesto again and are working with different communities in Baroda, Sydney, Basel, Berlin, London and Udonthani village, due to the need to stay together during the pandemic and lockdown. Each representative of Womanifesto gathered a number of women together to think and practice intimacy. For me, it was a very important gesture. These are not made for exhibiting, but represent the existential need for being together and thinking together through difficult times. I have proposed to Womanifesto to show only archival material that could be touched and the original artworks, rather than copies. They understood right away importance of having these fragile materials exposed to the user, and so they agreed.So, we selected several tools from the past that could bring visitors into the context by not only watching, but touching and sensing as well. I have to admit that working with the museum was a very important process, in order to recognize where we are heading and to actually support this process.

Womanifesto"group in Berlin grathing

Su: During the epidemic, Womanifesto reunited in six regions, and the members worked together through the epidemic by discussing, speaking, talking, performing, crafting, and creating works. The entire exhibition reveals a tension that is worth discussing: you didn't present an indigenous narrative of these collective actions in the exhibition, and at the same time you didn’t over-amplify

the anxiety of the individuals in the epidemic. This loose and modest narrative, which is conducted in the tension between emotion and artistic practice, reveals a rare quality of art practice. Can you talk about how you understand their practice in the period 2020-2021?

Ciric: It is necessary, it is art as an essential service that we need to fight for. We need to think what role art plays in the times that we are living in, and how we perform that essential service. They continue to work together. As I mentioned above, India is going through the hardest wave of coronavirus, while other places are back to normal. What we have shown in this exhibition is just one moment in time of that long relationship. It is an ongoing process, so we will show one more moment at the end of the year. There are many issues that these gatherings create which I didn’t want to theorize: violence on woman and other forms of domestic violence during lockdowns and the pandemic; the importance of mentorship and inter-generational ties, as many younger generations of artist joined these gathering among many others; practice of care.

Su: Spirit of Friendship is an ongoing research-based project initiated by the Factory Contemporary Art Center in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, an exhibition that dates back to a synonymous exhibition organized by the same institution in 2017, focusing on the lineage of Vietnamese contemporary art since 1975. This exhibition in Guangzhou, co-curated by Zoe Butt, Bill Nguyen, and Le Chien Pao, consists of extensive documentation, chronology, artist interviews, and a vast history behind year labels that viewers crouch down to flip through. This exhibition reminds me of the research you did on thehistory of exhibitions in Shanghai (1979-2006). Is there any parallel between the two?

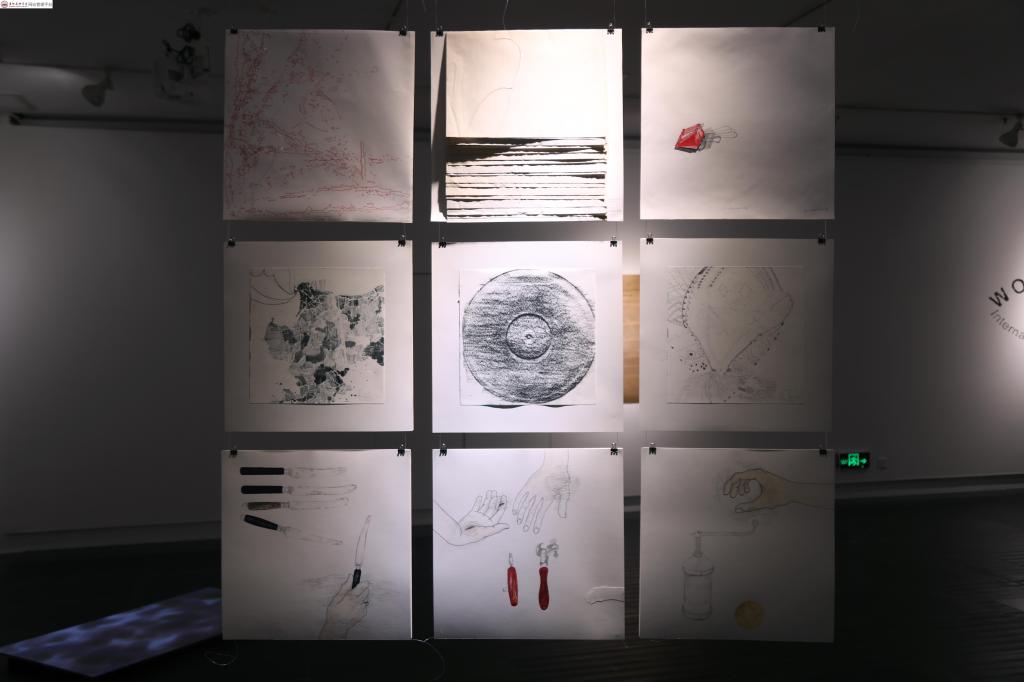

"SOF"part 2 "The way to survive"describle the artists how to create the special art space to present art

Ciric: As you know Su Wei, I have always found it crucial to work locally and make the conditions for situated knowledge to happen. And as you know, these conditions are not always there for you. You need to create these conditions.

This kind of local research is rarely discussed through big scale exhibitions, but they are so crucial when we think of how to practice and create different historical and international narratives or viewpoints. My research on exhibition histories in Shanghai, Spirit of Friendship and similar research brought an important contribution to the world from a very micro perspective. These archival works and contextualizations are still very rare today. Vietnam’s contemporary art scene until today was created to explore that very relationality generated by the community, and Spirit of Friendship tries to unpack its complexities. It also unpacks curatorial and artistic strategies on how to deal with what could be said and how, what is revealed and to what extent, how we read through more content. These are very important references for careful viewing in our ever shrinking public sphere.

Su: The lack of infrastructure and the reliance on the spontaneous spirit and friendship of art practitioners to push art forward is not new to us, and the same story is still happening even

in the seemingly prosperous field of Chinese contemporary art. Can you give a historical perspective on some of the under-appreciated threads in Vietnamese contemporary art, such as the mechanisms of patronage, how art practitioners opened up a dialogue with the globe, etc.? What kind of significant divergences among Vietnamese art practitioners have emerged during those years?

Ciric: I find these references are important points to think about today what international art we produce, and what tools we use to produce international art. What tools do we use? What gestures do we put forward? These are important things to revisit or listen to deeply as a proposition towards thinking about how we might work differently, or as a gesture to unlearn modes of working based on extractivist logic. The contemporary art scene of Vietnam went on a similar trajectory with its relationship to the world in early times, but without much capital and market until today. The gap between state and private institutions is vast. Institutions, like the Factory Center for Contemporary Art, are there for their communities, and these are very important gestures. Of course, I more and more understand institutions as Temporary Autonomous Zones, where the vision of people working there frame its direction. So, if there were no Zoe Butt and her colleagues, I am sure that Factory would have a different focus. But until today, it remains one of the few institutions producing situated knowledge.

Exhibition model 2017 of Vietnam factory Contemporary Art Center